Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › John Coltrane

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Die erste LP hat leider einen deutlichen Höhenschlag. Wird umgetauscht, obwohl ich wenig Hoffnung habe, dass die anderen Ausgaben besser sind.

zuletzt geändert von stardog

Bezieht sich auf die „Evenings At The Village Gate“--

Highlights von Rolling-Stone.deQueen: Darum war ihr Live-Aid-Konzert nicht wirklich spektakulär

25 Jahre „Parachutes“ von Coldplay: Traurige Zuversicht

Paul McCartney kostete „Wetten dass..?“-Moderator Wolfgang Lippert den Job

Xavier Naidoo: Das „Ich bin Rassist“-Interview in voller Länge

Die 75 schönsten Hochzeitslieder – für Kirche, Standesamt und Feier

Jim Morrison: Waidwunder Crooner und animalischer Eroberer

WerbungstardogDie erste LP hat leider einen deutlichen Höhenschlag. Wird umgetauscht, obwohl ich wenig Hoffnung habe, dass die anderen Ausgaben besser sind. Bezieht sich auf die „Evenings At The Village Gate“

Also meine ist in Ordnung, außer dezenter Verfärbung im Vinyl nichts zu bemängeln!

--

Hat Zappa und Bob Marley noch live erlebt!Ok, dann bin ich mal auf die zweite Lieferung gespannt.

--

gypsy-tail-wind

Hatten wir glaub ich schon mal irgendwo kurz? Jetzt sind konkrete Infos und ein Vorabtrack da:

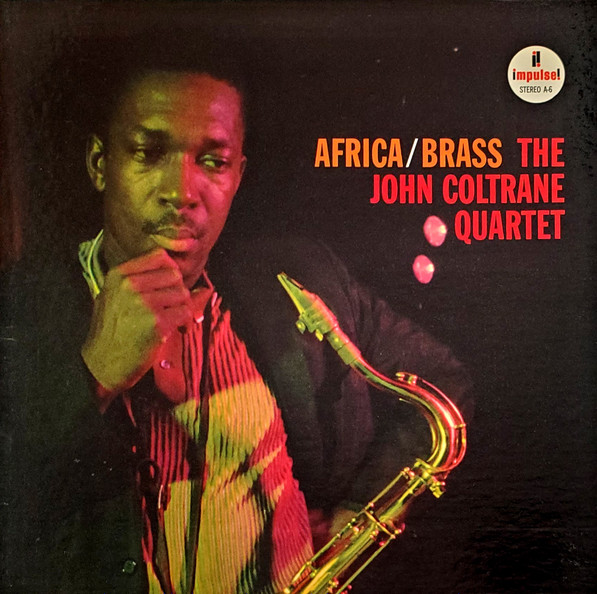

John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy: Evenings at the Village Gate

(2LP / CD / DL, 14. Juli 2023 + T-Shirts, Tote-Bags und ein Mug)In August of 1961, the John Coltrane Quintet played an engagement at the legendary Village Gate in Greenwich Village, New York. Eighty minutes of never-before-heard music from this group were recently discovered at the New York Public Library. In addition to some well-known Coltrane material (“Impressions”), there is a breathtaking feature for Dolphy’s bass clarinet on “When Lights Are Low” and the only known non-studio recording of Coltrane’s composition “Africa”, from the Africa/Brass album.

Tracklist:

1. My Favorite Things

2. When Lights Are Low

3. Impressions

4. Greensleeves

5. Africa

https://jazz.centerstagestore.com/pages/john-coltraneA little over 60 years ago, the editor-in-chief of DownBeat magazine asked John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy a deceptively simple question: What are you trying to do? He rephrased slightly: What are you doing? The two saxophonists sat for a long 30 seconds before Dolphy broke the silence. „That’s a good question,“ he said.

The DownBeat editor, Don DeMicheal, printed this exchange in the April 1962 issue, as part of a fascinating article headlined „John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy Answer the Jazz Critics.“ Regular readers of the magazine would have known precisely what provoked this gesture: a scathing review of Coltrane’s quintet with Dolphy, decrying „an anarchistic course in their music that can but be termed anti-jazz.“

1961 had been a prolific and pivotal year for Coltrane. That spring, his sleek, intriguing quartet version of „My Favorite Things,“ from The Sound of Music, became a breakout hit. But later that year, as he signed to a new label, Impulse! Records, he wasn’t putting a premium on commercial success. Instead, he was exploring new sounds and configurations, often testing ideas on the bandstand. One such idea was the addition of Dolphy, a wildly original voice on both reeds and flute, and a close personal friend.

The intrepid depth of their musical rapport takes center stage on a stunning new archival release, Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy, which Impulse will release on July 14. Tomorrow the label will share a preview track, „Impressions,“ featuring Coltrane on soprano saxophone and Dolphy on alto saxophone and bass clarinet — along with drummer Elvin Jones, pianist McCoy Tyner and bassist Reggie Workman, who together make the song feel something like a runaway train. (Until then, you can hear it — exclusively — here.)

Noch eine Passage, in der Ben Ratliff sich dazu äussert (zu den bekannten Village Vanguard-Aufnahmen vom November 1961 und dann auch zu den neuen):

Those Village Vanguard tapes, which later yielded a monumental four-disc set, amount to one of the most mysterious and thrilling documents in jazz history. A couple of years ago, Ben Ratliff, author of Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, placed this music within a cultural context of „ambivalent possibility,“ in a vivid essay for the Washington Post titled „John Coltrane and the Essence of 1961.“ He observes: „The music sounds post-heroic and pre-cynical; interestingly free from grandiosity; full of room for the listener to find a place within it and make up their own mind.“

Last week, after hearing the version of „Impressions“ from Evenings at the Gate, Ratliff elaborated on this idea. „It’s very hard to label or encapsulate, but it’s just so ferociously full of life force,“ he said of the performance. „The musicians know how good this is, and they know how exciting it is — but beyond that, they don’t really know much, and it hasn’t been called anything yet. There’s a lot of the unknown here.“

Weiterlesen und reinhören:

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/31/1179098682/john-coltrane-eric-dolphy-village-gate-1961-lost-album__

Das Material stammt von diesem Auftritt (der erste mit Dolphy glaub ich?):

Village Gate, NYC, July 11-23

John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones and Reggie WorkmanDie Geschichte der Entdeckung der Bänder:

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2023/07/28/how-pair-unreleased-john-coltrane-tapes-surfaced-nypl--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #164: Neuheiten aus dem Archiv, 10.6., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaOh Mann, lese gerade über die Rezension von Downbeat 1961 zu Africa/Brass. Hat schon was peinliches, zumal das Album auch ganz nüchtern betrachtet recht zugänglich ist. Die „zuständigen“ Lordsiegelbewahrer der Musikkritik mal wieder:

Downbeat-writer Martin Williams gave it two stars out of possible five, complaining about a lack of melodic development as well as »technical order and logic.«

--

Tout en haut d'une forteresse, offerte aux vents les plus clairs, totalement soumise au soleil, aveuglée par la lumière et jamais dans les coins d'ombre, j'écoute.hier ist die ganze Rezension, Downbeat vom 18. Januar 1962

Certainly no one could question Coltrane’s particular skill as a tenor saxophonist. Nor that his ear for harmony, his knowledge of it, and his use of it, can fascinate. Nor do I question that his playing is honestly emotional, if, to me, somewhat diffusely so. What I do question is whether here this exposition of skills adds up to anything more than a dazzling and passionate array of scales and arpeggios, if one looks for melodic development or even for some sort of technical order or logic, he may find none here. In these pieces, Coltrane has done on record what he has done so often in person lately, make everything into a handful of chords, frequently only two or three, and run them in every conceivable way, offering what is, in effect, an extended cadenza to a piece that never gets played, a prolonged montuna interlude surrounded by no rhumba or son, or a very long vamp ’til ready. Africa is African by the suggestion of its rhythms. It has some brass figures that, for me, get a bit too monotonous to add variety and which are also in general too much in the background to add much of their own. I must say that Workman and Davis, particularly when they work together, fascinated me, and that Tyner plays a good solo. These three also manage to swing, and they provide one of the few instances of real swing in this recital. Greensleeves is converted into a 6/8 Gospel-like meter, but once you have the hang of that, after a chorus or two, you have the hang of that. On Blues Minor, which seems to me uncomfortably close to Bags’ Groove, Coltrane again begins a kind of ingenious workout on a couple of repeated chords after a chorus or so. The point is not that it is impossible to make high art out of very simple materials. Many a blues player can make fascinating music on three chords, two chords, one chord—even no chords really. Nor that it is impossible to make fine jazz solos out of arpeggios: Jimmy Noone did it, Coleman Hawkins does it, Coltrane has done it. Perhaps my remark in the beginning about emotion does hold an answer. After all, Noone and Hawkins both have a directness and organization of feeling within each piece and a variety of feeling from one piece to the next.

Martin Williams hatte in dem Heft übrigens nur eine weitere Rezension, Soft Vibes, Soaring Strings von Lionel Hampton, da gab er *.

--

.auf wikipedia verweisen sie ja auch auf die Gedanken von Steve Reich, Wegbereiter der Minimal Music, zu Africa/Brass hier… die erklären mE ganz gut, warum das Album für damalige, bop-geschulte Ohren vielleicht gewöhnungsbedürftiger war als für uns heute…

Anybody with a pair of ears should listen to Coltrane. I highly recommend an album called Africa / Brass. Not necessarily the most famous, but for musicians in terms of an extreme form. It’s about half and hour long and it’s got a very big band and Eric Dolphy did the arrangements. I think there are French horns playing like elephants coming through the jungle. But what’s interesting is that the whole 30 minutes are in E. You know how jazz men talk about the changes? “What’s the change?” “E.” “No, no, no, what’s the changes?” “E!” E for half an hour. “Wait a minute, come on, E for half an hour?” Well, it’s built on the low E of the double bass, played by Jimmy Garrison. You’d say, “No, it’s stupid. That’s too boring.” But it’s not. It’s definitely not boring. Why? What’s going on to compensate for the lack of harmonic movement? Now of course, you live in a time when we’ve had a lot of water under the bridge. But I’m talking 1963, ’64, ’65. There’s incredible melodic invention, sometimes Coltrane’s playing gorgeous melodies, sometimes he’s screaming noise through the horn. Sometimes these elephant glissandos going on, which are basically French horns playing glissandos, scored by Eric Dolphy, who was a great musician and one of the great alto sax players and a very schooled musician as well. And two drummers, Elvin Jones being one of the most inventive jazz drummers who ever lived. And I think Rashied Ali was the other drummer. So you’ve got an incredible amount of rhythmic complexity, temporal variety and melodic invention. And they more than compensate for the harmonic consistency. As a matter of fact, there’s a tension because it doesn’t change.

(die zwei Drummer sind natürlich blödsinn, nehme an er meint die zwei Bassisten und vermischt was)

--

.Von Giant Steps hatten sich die Brüder von Atlantic kommerziell auch mehr erhofft, stimmt’s? Die Kritiken waren ja auch nicht gerade mit einem Kniefall vergleichbar.

Dieses „bop-geschulte Ohren vs. heutige Hörer“-Argument klingt zu gemütlich. Besser gleich unverblümt darlegen, warum Africa/Brass für einen 1961er-Bebop-Puristen für das etablierte Bewertungskollegium wie ein Schock wirkte.

zuletzt geändert von kingberzerk--

Tout en haut d'une forteresse, offerte aux vents les plus clairs, totalement soumise au soleil, aveuglée par la lumière et jamais dans les coins d'ombre, j'écoute.Giant Steps kriegte auf jeden Fall ***** von Ralph Gleason (Downbeat vom 31.3.1960)

There seems to exist some feeling that John Coltrane, while granting him his importance as a major tenor influence, is a harsh-sounding player to whom it is difficult to listen. This LP, if it does nothing else, should dispel that idea quickly. There are times here when Coltrane is remarkably soft, lyrical and just plain pretty. For instance on Naima, which is an original as are all the tunes in the LP, JC starts out calling the title almost on his horn (it’s his wife’s name, by the way) in a hauntingly beautiful passage. Then again at the end of the same tune, JC cries wistfully and poignantly on the horn. In Syeeda’s Song Flute there’s a throw-away phrase just before Tommy Flanagan’s piano solo that is exquisite in its beauty. Of course the usual Coltrane forceful playing is present all over the album. The title song (which has echoes of Tune Up) is an example of this and so is Countdown which has a particularly intriguing tenor and drum duet in the front of the tune, as well as a great, soaring ending. Paul Chambers works particularly well with Coltrane and on the final track there is some hard digging by PC which is the kind of thing you put the arm back to over and over. It is no wonder that JC is making such an impression on tenor players. He has managed to combine all the swing of Pres with the virility of Hawkins and added to it a highly individual, personal sound as well as a complex and logical, and therefore fascinating, mind. You can tag this LP as one of the important ones.

und My Favorite Things kriegte auch *****, am 22. Juni 1961 von Pete Welding, der sich scheinbr an kein word limit halten musste…

This collection is nothing short of magnificent. These four assured and powerful tracks are the statements of a mature(and major) stylist who has evolved a cogent and gripping approach of real individuality.There are no loose ends here;all the disparate elements of his style have fallen into place for Coltrane, and a synthesishas been effected.

It’s been a long road for Coltrane. Ever since he left the Miles Davis Quintet in August, 1959, he has been subjecting himself to a rigorous artistic discipline in an attempt to bring all the wayward elements of his style under complete control. The restless, tortured convolutions of his early work and the resultant harsh brusqueness have here given way to a sure technical mastery, a sweeping grace, and an expressive lyricism in which there is no diminution of the power and urgency one always felt in his playing (just listen to Summertime). No, here he is completely in control all the time, and, for the first time, one senses that Coltrane is able to shape the direction of each piece in its entirety. Quite often in the past Coltrane seemed not always to be complete master of his improvisations; frequently they seemed to get away from him. Not so here, however, for each of the four pieces has a rightness and inevitability about it that comes of steady sure guidance and a purposeful knowledge of where one wants to go.

There are two major pieces here, one on each of Coltrane’s instruments, tenor and soprano. The first of these — the title piece, played on the smaller horn—is set to a delightfully “sprung” waltz rhythm effortlessly generated by Jones, whose drumming throughout is both sensitive and propulsive. Coltrane sets the mood and character of the piece in his initial solo, which consists primarily of a straightforward exposition of the theme, with little embellishment. A definite Middle Eastern flavor is established through his sensitive use of slight arabesques and shrill cries. This is picked up and amplified in his second solo, which is developed through a series of long lines that can be described only as sinuous and serpentine. At times there is employment of a pinched, high-pitched, near-human cry of anguish that is most effective, and at one point near the end of this surging, extended improvisation, he uses a device that sent chills along my spine: he seems to be playing a slithering, coruscating melody line over a constant drone note! Pianist Tyner’s spare, percussive solo separates the two horn segments. He seems to see the futility of trying to compete with Coltrane on any sort of linear basis and contributes an almost entirely chordal solo that sustains the mood of the piece beautifully.

The second soprano number, Everytime, is pretty much a standard ballad interpretation — lush, direct, and greatly romantic. It’s played fairly straight, with little improvisational development, the intense emotionality of the number being generated by the great feeling with which it is executed. Coltrane has been playing soprano for slightly more than a year now and has mastered it. He gets a dry, airy (almost hard) tone on it, which is at the opposite pole from that of the late Sidney Bechet’s warm, glutinous, sensuousness on the same instrument. One is tempted to say that Coltrane is already the second significant innovator on this instrument and let it go at that.

The second major number in the album is Summertime, which is a brilliant tour de force on tenor. As on My Favorite Things, Coltrane has two solo segments, broken by Tyner’s discreet piano. Both of Coltrane’s lengthy extemporizations on this piece are brooding, blistering examples of the rapid, multinote approach that has been labeled his sheets-of-sound technique. In fact, the use of this device is so sustained that each of the two solo segments might be considered a solid sheet of sound, for each consists oi a relentless, powerful cascade of notes delivered with such amazing speed and force that an astonishing harmonic density results. It’s quite unlike any previous usage he’s made of his technique.

But Not for Me is developed along these same lines, but to a lesser degree, and the use of the device is neither so extensive nor so sustained. Coltrane’s previous albums have emphasized various aspects of the style that is fully and finally crystallized in this impassioned, fully realized collection. If these four numbers are his “favorite things,” it’s easy to see why.--

.Bags & Trane kriegte ***1/2 am 28.9. 1961 und Olé kriegte ebenfalls ***1/2 am 1.2.1962, also quasi ein Heft nach Africa / Brass. Am 15.3.1962 kam dann Settin‘ the Pace mit ****1/2 von Ira Gitler und am 26.4.1962 kam dann Live at Village Vanguard, ein kontroverses Album, das in einer Doppel-Rezension von Ira Gitler (**1/2, Coltrane may be searching for new avenues of expression, but if it is going to take this form of yawps, squawks, and countless repetitive runs, then it should be confined to the woodshed. Whether or not it is “far out” is not the question. Whatever it is, it is monotonous, a treadmill to the Kingdom of Boredom. There are places when his horn actually sounds as if it is in need of repair. In fact, this solo could be described as one big air-leak.) und Pete Welding (***1/2) besprochen wurrde… Anders gesagt: da kamen in relativ hohem Tempo sehr sehr viele Alben auf den Markt…

--

.Am 11.10. 1962 wurden dann das fünfte und sechste neue Coltrane Album des Jahres rezensiert, zum ersten Mal zwei in einer einzigen Rezension, das Atlantic Album „Plays the Blues“(***1/2) und das Impulse Album Coltrane (****1/2)… aber Rezensent Don DeMichael fragt sich auch: how much longer can Coltrane continue to find new and exciting things in what has become a limited approach,

as stimulating as it may be? Certainly most of his work is of high order, but even now much of what is played is similar in mood and effect.dann fehlen mir ein paar Hefte, in denen wohl Ballads und das Album mit Ellington drin wären… und am 29.8.1963 gibt es dann mal wieder *****, diesmal von Harvey Pekar für Impressions… am 10.10.1963 bespricht dann John Tynan das Album mit Johnny Hartman sehr positiv in seiner vocal jazz Kolumne, in der nicht besternt wird, „The record proves [..] that a good, romantic ballad singer is by no means out of place with a modern jazz group. In fact, singer and instrumentalists Coltrane, pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist

Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones complement one another in this nigh ideal pairing“--

.Sehr hilfreich, danke! Dann zur wahren Challenge. Was war dann mit „Ascension“?

--

Tout en haut d'une forteresse, offerte aux vents les plus clairs, totalement soumise au soleil, aveuglée par la lumière et jamais dans les coins d'ombre, j'écoute.vor Ascension hab ich auch ein bisschen Angst… aber gerade bin ich beim 9. April 1964, Big Band Arrangeur Bill Mathieu beginnt seinr Rezension von Live at Birdland (****) mit einer allgemeinen Bemerkung

If white critics can stand in any relation at all to Negro jazz of this caliber ( it is not obvious that we can) then that relation must be humble, but it also may be malcontent. The dignity that propels Coltrane’s music is dignity beyond the immediate grasp of the average man, especially the average white man, whose idea of dignity is born in relative peace. It is the high level of emotional sincerity that makes this music not only good music but good instruction as well.

Die Bemerkung mag von Amiri Baraka’s Liner Notes inspiriert sein, die er besonders hervorhebt… den Stern Abzug gibt es einmal mehr dafür, dass es nur zwei Akkorde gibt, weswegen McCoy Tyner nicht optimal zur Geltung kommt…

Am 8. Oktober 1964 ist Matthieu dann gleich wieder dran, mit einer Doppelrezension von Coltrane’s Sound (****) und Crescent (***1/2)

Coltrane’s Sound was recorded about three years ago and is representative of Coltrane’s best playing of that period. Crescent was made in spring, 1964; it does not give the best of current Coltrane. A comparison of the two albums, then, is not entirely balanced. Both records, however, give a fairly good look at the quartet and how it functions. The highest point in the

die Kritik ist die gleiche wie bei Live At Birdland (und irgendwie ja auch schon bei Africa / Brass)…

As the drone drones, it spells safety to Coltrane, and if Coltrane is safe, Coltrane is, alas, dull. The further out he searches, the more his music means. The reason these records do not mean more to me is that most of the time I am pinned to a fixed pedal-point. No freedom is worth such restriction, at least not in jazz, not in 1964, not for such a leader. And the more recent record is the more disappointing because it shows exactly how the issue has not been resolved. Coltrane has not yet found a way to break the harmonic stasis. One might ask why is Coltrane greatest when he departs from it furthest? Has this correlation occurred to Coltrane? Rest assured it has.

--

.Am 8. April 1965 bespricht Don De Michael dann A Love Supreme (*****),

Musically, Coltrane is very much together on this record. The excesses of the

past are conquered. Everything counts; nothing sprawls.heisst es zB und

This is a significant album, because Coltrane has brought together the promising but underdeveloped aspects of his previous work; has shorn, compressed, extended, and tamed them; and has emerged a greater artist for it.

am 2. Dezember 1965 folgt dann eine Rezension von „The John Coltrane Quartet Plays“ (****1/2) von Richard B Hadlock… am 30. Dezember darf dann A B Spelman ein Coltrane Konzert aus dem Village Gate rezensieren, mit einer grösseren Band:

John Coltrane, soprano and tenor saxophones; Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, tenor saxophones; Carlos Ward, alto saxophone; McCoy Tyner, piano; Jimmy Garrison, bass; Rashid Ali, Elvin Jones, drums.

The band John Coltrane showed at the Gate Nov. 10 might be called „J. C. & After.“ Coltrane, who put the kinetic field back into the tenor saxophone after it had been lost when the Illinois Jacquets disappeared from Respectability ( a small, affluent suburb of New York), assembled an aggregation of reed men who were learning their fingering when he was cutting Blue Trane; their harmony when he was cutting Milestones; their selves when he was cutting Coltrane’s Music.

Trane, with his Ascension record date and with the augmented quartet he uses in the clubs, is not only creating a band with more power than Con Ed but is also introducing some of the best of the New Jazz musicians to the World of the Living Wage and, thereby, performing a double service. Shepp and Saunders, by virtue of the discomforting weight of their music, get precious few gigs, and Coltrane, by presenting their music in its proper musicological context, is performing a great service to their generation. Both these men have highly distinctive styles. They really sound nothing like Coltrane, but it is clear that they have benefited from Coltrane’s line, harmonics, and dissection of a song’s melody.

hoffe ich find jetzt was zu Ascension…

--

.Am 5.5.1966 durfte dann Coltrane-Spezialist Bill Matthieu zum vierten Mal ran, diesmal mit einem „spotlight review“… und er gab zum ersten Mal den fünften Stern – man könnte jetzt sagen, dass einem Big Band Arrangeur wie Matthieu natürlich Ascension mehr liegen muss als Crescent oder Live at Birdland… aber ganz so klar war das eigentlich nicht… hier ist der ganze Review:

This is possibly the most powerful human sound ever recorded. Coltrane has collected 10 other soloists, each a distinctive voice in contemporary jazz. All hold in common the ability to scream loud and long. If the music coheres, it does so because everyone is screaming about the same thing. The album is a recording of a single work which lasts more than 35 minutes. In the liner notes, Shepp speaks of the music this way: “It achieves a certain kind of unity; it starts at a high level of intensity with the horns playing high and the other pieces playing low. This gets a quality of like male and female voices. It builds in intensity through all the solo passages, brass and reeds, until it gets to the final section where the rhythm section takes over and brings it back down to the level it started at. . . . The ensemble passages were based on chords, but these chords were optional. What Trane did was to relate or juxtapose tonally centered ideas and atonal elements, along with melodic and nonmelodic elements. In those descending chords there is a definite tonal center, like a B-flat minor. But there are different roads to that center.”

In the notes. Brown says that the music has “that kind of thing that makes people scream. The people who were in Ihe studio were screaming. . . . You could use this record to heat up the apartment on those cold winter days.” There are two things to consider here. The first is the actual experience these musicians shared in the recording studio on June 23, 1965. The other is this phonograph record of the event. Ordinarily we can accept these two things as one. The differences, though important, are not crucial. True, one had to “be there” when Horowitz returned to the concert stage last year in Carnegie Hall. But the recording of that concert captures enough for us to re-create the event through the music. In fact, the music transcends the event. The event has meaning through focused concentration on the quality of the music. This is not so in the case of Ascension. The vitality of this music is not separable from “being there,“ The music does not transcend the event. In fact, the music is the event, and since there is no way of reproducing (i.e., reliving) the event except by doing it again, the music is in essence nonrecordable. This brings us to a difficult subject involving not only this music but also much other contemporary art. In our growing esthetic, “the moment” emerges as sacred. The “now” is the reality from which a new esthetic of the religious is flowing. Perishable sculpture points this out to the observer. Musicians like John Cage offer variations on this theme. Present time has always been most crucial to jazz. Yet nowadays, as a revolution

crystallizes, what was once merely crucial is now the thing itself. This revolution, this black one, has a vested interest in “now” as opposed to “then.” The forces that spawned it are wasting no love on old things. The old order was “then.” It passeth to “now.” No one alive today can remember a more concerted cry for a new social being. Ascension is (among other things) at the center of this cry. The spiritual commitment to present time vibrates around Earth; the vibration is focused and intensified in music like this. To offer it on a “recording” is in some sense against the thing itself. Ascension is a recording not of an event, but of the sounds made during an event, and these sounds by themselves do not give us the essence of the event. If the listener is informed enough to be able lo imagine what it was really like when this event took place, then the record may have meaning. But it would seem that a listener so informed would not especially need or want a reminder of another “then.” It is my feeling that gradually there will come a music informed by the freedom and power of Ascension, but which has more artistic commitment beyond the moment of recording. Such music is already forming (although with less muscle—no music matches Ascension for sheer strength and volume.) The few moments when Tchicai is soloing constitute one of several places where this more subtle light shines through strongest. Distinctions are close; everything seems about to happen. Meanwhile, it is useful to regard this album as a documentation of a particular space of history. As such, it is wonderful—because the history is. If you want immersion in the sounds of these men, if you want their cries to pierce you, if you want a record of the enormity and truth of their strength, here it is.--

. -

Schlagwörter: Free Jazz, Hard Bop, Jazz, John Coltrane

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.