Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Dollar Brand – The African Recordings

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Der allgemeine Abdullah Ibrahim Thread findet sich hier:

http://forum.rollingstone.de/foren/topic/abdullah-ibrahim/—

In den letzten Tagen und Wochen habe ich wieder einmal die zum grössten Teil von 1974/75 stammenden „African Recordings“ von Abdullah Ibrahim angehört, der damals noch unter dem Namen Dollar Brand bekannt war – sein eigentlicher Name war Adolph Johannes Brand, daraus wurde dann „Dollar“, Mitte der 70er konvertierte er zu Islam und nennt sich seither Abdullah Ibrahim.

Die Aufnahmen sind auf einer Reihe von vier CDs greifbar, die zuerst Ende der 80er Jahre auf dem Label Kaz (auch als Doppel-LPs) und dann zehn Jahre später wieder (mit denselben Titeln aber anderen Covern) bei Camden erschienen sind: „African Sun“, „Blues for a Hip King“, „Tintiniyana“ und „Voice of Africa“.

Zudem erschienen bei Kaz/Camden auch zwei Volumes „Jazz in Africa“. Volume 1 enthält den grösseren Teil der beiden Alben, die 1959 mit Hugh Masekela, Kippie Moeketsi und Jonas Gwanga entstanden sind: „Verse 1“ von den Jazz Epistles (mit Brand am Piano und auch als Gallo CD komplett greifbar) sowie „Jazz in Africa“ des amerikanischen Pianisten Johnny Mehegan. Diese Aufnahmen gehören nicht eigentlich zur Gruppe von Aufnahmen, um die es hier geht. (Weitere Details dazu finden sich in Doug Paynes hervorragenden Hugh Masekela Diskographie.)

Auf „Jazz in Africa Volume Two“ hingegen findet sich an erster Stelle ein verwandtes Album aus derselben Zeit, „Tshona“ von Pat Matshikiza & Kippie Moeketsi (feat. Basil „Mannenberg“ Coetzee), danach folgen zwei weitere lange Stücke, davon eins („Kalahari“) das zu Brands „African Recordings“ gehört, sowie eins mit Musikern, die auch an diversen Brand-Sessions beteiligt waren, aber mit Tete Mbambisa am Piano (zu diesem Stück, „African Day“, konnte ich bisher keine diskographischen Angaben finden, die Angaben bei Lord beziehen sich bloss auf die betreffende Kaz-CD).

Ein paar weitere Stücke mit und ohne Ibrahim (auch zwei mit Bheki Mseleku) sind auf der tollen Kaz/Camden-CD „African Horns“ zu finden.

—

Hier die Informationen, die ich aus den Diskographien von Tom Lord und Walter Bruyninckx, von Discogs.com und anderen Websiten zusammengetragen habe:

<b>LPs:</b>

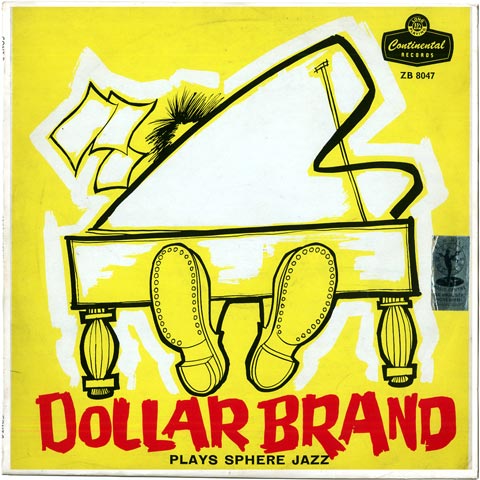

Gallo-Cont ZB8047 – Dollar Brand Plays Sphere Jazz

A: Boulevard East, Khumbula Jane, King Kong / B: Blues for B, Misterioso, Just You…, Eclipse at DawnSoultown KRS113 – Dollar Brand + 3 with Kippie Moeketsi

A: African Sun, Bra Joe…, Old Folks / B: Rolling, You Are Too Beautiful, Memories of YouSoultown KRS114 – Underground In Africa

A: Kalahari / B: Ornette’s Cornet, All Day & All Night Long, GwidzaThe Sun SRK 786134 – Mannenberg – ‚Is Where It’s Happening‘ (+ The Sun CD)

A: Mannenberg / B: The Pilgrim

= Chiaroscuro Records CR 2004The Sun SRK 786136 – Blues for a Hip King

A: Monk in Harlem, Sweet Basil Blues / B: Tsakwe, Blues for a Hip KingThe Sun SRK 786138 – Black Lightning

A: Black Lightning / B: Little Boy, Black & Brown Cherries, Blue MonkThe Sun SRK 786139 – Natural Rhythm

A: Kentucky, Nobody Knows…, Ntyilo Ntyilo / B: Thaba Nchu, Blues for „B“, LargoThe Sun SRK 786141 – Dollar Brand Plays Sphere Jazz

Reissue of Gallo-Cont (SA)ZB8047The Sun SRK 786142 – Dollar Brand & Kippie Moeketsi / Dollar Brand + 3

Reissue of Soultown KRS 113The Sun SRK 786143 – Underground in Africa

Reissue of Soultown KRS114The Sun SRK 786145 – Bra Joe From Kilimanjaro

A: Bra Joe from Kilimanjaro / B: KamalieChiaroscuro CR2012 – Soweto

A: Soweto / B: African Herbs, Sathima—

<b>CDs</b> (Kaz/Camden)

AH = Various: African Horns

AS = African Sun

BHK = Blues for a Hip King

JiA2 = Various: Jazz in Africa Volume Two

T = Tintinyana

VOA = Voice of Africa—

Ich möchte im folgenden die Angaben zu den einzelnen Sessions posten, hie und da auch etwas zur Musik sagen – und wenn möglich offene Fragen und Unklarheiten klären (werde mich auch anderswo privat etwas Umhören und gegebenenfalls Updates posten hier).

Ein Hinweis hier noch auf einen Sammel-Review einiger dieser Aufnahme auf AAJ:

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/southafrica/raredollar.htm

Auch das ist eher chaotisch und teils verwirrend – klärt aber z.B. die bis heute nie korrigierten Allmusic.com-Angaben zum Chiaroscuro-Release Soweto.--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaHighlights von Rolling-Stone.deSinéad O’Connor: Das symbolisierte ihr rasierter Kopf

Jim Morrison: Waidwunder Crooner und animalischer Eroberer

John Lennon: Sein Tod und die Geschichte seines Mörders

Silvester-Tipp von Phil Collins: Mit „In The Air Tonight“ ins neue Jahr

Die besten Musiker aller Zeiten: The Who – Essay von Eddie Vedder

Amazon Prime Video: Die wichtigsten Neuerscheinungen im Dezember

Werbung

Scan von hier, wo viele weitere Scans, Details und auch die Liner Notes zu finden sind:

http://www.flatinternational.org/template_volume.php?volume_id=186Dollar Brand Plays Sphere Jazz (Gallo-Cont (SA)ZB8047)

Dollar Brand (p) Johnny Gertze (b) Makaya Ntshoko (d)

South Africa, prob. Johannesburg, February 4, 1960 (issued 1962)Boulevard East

Khumbula Jane

Sad Times, Bad Times

King Kong

Blues for B

Misterioso

Just You, Just Me

Eclipse of DawnNotes :

All titles also on: The Sun SRK 786 141 and Kaz LP104.

All titles except „Boulevard East“ and „Sad Times…“ also on CD BHK

„Sad Time…“ not listed on Cover of Gallo-Cont – not sure it’s on the Kaz and Camden reissues (as Lord’s discography says) or not.

All Kaz and Camden reissues titled „Blues for a Hip King“.

Bruyninckx says bassist is Gertze or Victor Ntoni and gives date as October 1971.Die Musik klingt eindeutig nach 1960 und nicht nach 1971! Brand spielt hier Monk („Sphere Jazz“), den Standard „Body and Soul“, Todd Matshikizas tolles „King Kong“-Thema und ein paar Eigenkompositionen, sowie ein Stück von Mackay Davashe, „Khumbula Jane“.

Das Trio klingt sophisticated, Brand pflegt einen warmen Stil, sein Spiel ist im Vergleich zu den frühen Aufnahmen mit den Jazz Epistles enorm gewachsen, viel organischer und weniger auf Effekt aus. Die Musik klingt stark nach amerikanischem Jazz, Brand sollte erst im selbstgewählten Exil der mittleren und späten 60er Jahre sich auf seine afrikanischen Wurzeln besinnen und entsprechende Elemente in seine Musik einbauen.

Leider fehlen zwei Stücke auf der CD „Blues for Hip King“, auf der der Grossteil von „Plays Sphere Jazz“ in völlig umgeworfener Abfolge auf #7-12 zu hören ist. Das abschliessende Davashe-Stück zählt jedenfalls zu den Höhepunkten. Das Stück „Eclipse at Dawn“ fand später Eingang ins Repertoire von Chris McGregors Brotherhood of Breath und wurde u.a. in Berlin 1971 gespielt (und zum Titel des Mitschnittes bestimmt, der vor einigen Jahren bei Cuneiform erschienen ist – sehr tolle CD übrigens).--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaHab mal seine Trio als Opener für Ray Brown auf einem Festival gesehen.Ich würdei die Musik eher als Weltmusik,denn als Jazz bezeichnen wollen.

--

Zum Album „Verse 1“ der Jazz Epistles hat Tony McGregor hier einen kleinen Text geschrieben:

http://hubpages.com/hub/Jazz-Epistles-Verse-One—a-Classic-South-African-Jazz-AlbumDie CD kann man hier finden:

http://www.kalahari.net/music/Verse-One/19738/143573.aspx

(Leider sind dort immer weniger südafrikanische Jazz-CDs zu finden – meine beiden Bestellungen dauerten zwar eine Weile, aber kamen unbeschädigt an, und der Versand ist nur verhältnismässig teuer, am Ende kamen die Bestellungen ziemlich günstig raus, auch wenn die Hälfte für den Versand drauf ging.)--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaEinen sehr spannenden Artikel über die Jahre, in denen der Grossteil von Brands „African Recordings“ entstand (1971-75) , und aus dem ich in der Folge auch ein wenig zitieren werde, findet sich hier:

http://asq.africa.ufl.edu/files/Mason-Vol9Issue4.pdfDie Bezeichnung „African Recordings“ stammt übrigens nicht von den ursprünglichen Alben, sondern von den Kaz und Camden CDs – sie scheint mir aber als Abgrenzung so schlecht nicht. Zudem muss ich noch anmerken, dass es sich bei diesen CDs um Bootlegs handelt – aber in den allermeisten Fällen (die Ausnahme ist „Mannenberg Is Where It’s Happening“) sind die Album leider in legitimer Form nicht auf CD und ohne ein Vermögen zu invenstieren überhaupt nicht mehr zu finden.

A sense of personal and political crisis drove Ibrahim back to Cape Town in 1968. Years of smoking and drinking had battered his body. In New York, doctors and a Native American medicine woman both told him to „straighten up.“ And he did, entering a period of „cleaning“ and embarking on a spiritual quest that began in New York City and culminated with his conversion to Islam, in Cape Town.[55] He was also concerned about the health of his country. He saw himself as „the voice of the voiceless“ and was determined to speak on their behalf.[56] Dollar Brand, the hard-drinking, alienated hipster, had given up the bottle and returned home to adopt a new religion, change his name, and espouse an iconoclastic brand of cultural nationalism in music, poetry, and polemics.[57] Capetonians, frankly, didn’t know what to do with him.

[55]. Drum, 22 September 1974, p. 35; Brand, 27 July 1968; Jaggi. Ibrahim gave up his birth name, Adolphus „Dollar“ Brand, upon his conversion to Islam.

[56]. Jaggi. Several of Ibrahim’s poems from the period can be found in Pieterse).

[57]. „Dollar Starts School.“Ibrahim begann im Cape Herald eine Reihe von Artikeln zu schreiben. Im ersten schon schrieb er, dass es für ihn keinen Grund gebe, weiter in der Fremde zu bleiben, Amerika könne ihm nichts über Musik beibringen: „Everything is here!“ (Lawrence, Howard. „Dollar Brand Back in Cape Town.“ Cape Herald, 20 July 1968, p. 3). Natürlich hat Brand in den USA einiges über Musik gelernt, sein Punkt war aber, dass in Südafrika alle Ingredienzien vorhanden waren, die es zum Entstehen einer lebendigen, eigenständigen Musikszene braucht.

Die Musiker in Südafrika orientierten sich damals allerdings – wie Brand zuvor ebenso – fast ausschliesslich an amerikanischen Vorbildern, wofür Brand sie auch angriff (ohne die Ausnahmen Gideon Nxumalo – mir bisher unbekannt – und Philip Tabane zu erwähnen).Ibrahim could overlook Nxumalo and Tabane because his primary audience was local. While his rhetoric encompassed all South African musicians and while his subject was music, he was, in fact, addressing the Cape Town jazz community, especially coloured musicians, and the coloured community as a whole. In some articles, Ibrahim did address the coloured community directly. He insisted that coloured people who were ashamed of their folk traditions–„the doekums and the Coons“–were, by extension, ashamed of themselves. He urged them to see their culture and themselves through his eyes. If they did, they would see that they were „all beautiful.“ „Look around you and see yourself,“ he wrote. „You are my music. My music is you.“[61] The music that he had in mind were his new compositions that he had begun to create in New York. He wrote of the ways in which they drew on virtually the entire musical universe of coloureds and Africans: the jazz of Kippie Moeketsi, the ghoema beat and minstrel tunes of the Coon Carnival, „Shangaan and Venda and Pedi“ folk songs, the Malay choirs of Cape Town’s coloured Muslims…. It was meant to be a suggestive list, not an exhaustive one. He wanted to embrace the entire nation, perhaps including whites, likening its people and their cultures to the protea, the national flower, which flourished in South Africa, but could survive only in greenhouses in foreign climes.[62] The protea also stood in for Ibrahim himself. In exile, he said, he found it „hard to play naturally.“ In South Africa, on the other hand, „the music just flows…. You don’t have to force yourself.“[63] Having reinvented himself and his music, Ibrahim was now inventing a radically innovative cultural identity, once coloured and inclusively South African, at once.

Ibrahim’s articles seem to have had no impact at all.[64] Looking back, the Cape Town jazz impresario Rashid Lombard said that Ibrahim was far ahead of his time. „Abdullah was one hundred percent right,“ but no one „could comprehend“ what he was saying.[65] Coloured intellectuals and activists instinctively recoiled from appeals to racial and ethnic particularity. In the absence of any direct criticism of apartheid, his celebration of distinctive coloured and African cultures seemed to resonate with the apartheid state’s efforts to reinforce ethnic and racial divisions in order to keep blacks weak and divided. Politically engaged coloureds and the coloured middle class would have hesitated to embrace the Coon Carnival because they were, as Ibrahim suggested, ashamed of this and other aspects of working-class culture. But they had a political critique of the Carnival, as well. Many viewed it as nothing more than „a show which reflect[ed] and confirm[ed] the subordination of its performers,“ an „annual act of debasement.“[66] Few coloureds of any class would have responded to his call to identify with Africans and African cultures. As Mohamed Adhikari points out, „only a tiny minority“ of coloureds were interested in anything resembling black unity. Most were determined to maintain their social and physical distance from Africans.[67] Finally, it certainly did not help Ibrahim’s cause that he published the articles in the Herald, a newspaper which devoted much of its ink to vivid descriptions of murder and rape and to effusive praise of conservative coloured politicians who collaborated with apartheid.

[61]. Brand, 27 July 1968 and 24 August 1968.

[62]. Brand, 27 July 1968.

[63]. Brand, 16 November 1968.

[64]. None of the many Cape Town musicians, music promoters, or political activists that I have interviewed remember the articles.

[65]. Rashid Lombard, interview with author, 5 February 2007.

[66]. Anderson, p. 103; Martin, p. 127.

[67]. Adhikari, p. 11. This point has been made many times. See, from the period, O’Toole, pp. 27-33.Ibrahim stiess vorerst weder beim Publikum noch bei den Musikern auf viel Gegenliebe oder überhaupt Interesse, seine Musik wurde als „rubbish“ bezeichnet, niemand war auf seine Mischung vorbereitet, in der die Grenzen zwischen Kunst und Folklore verflossen. 1969 verliess er Südafrika wieder, ging erneut in die USA – er konnte in Südafrika seine Familie nicht über die Runden bringen.

With engagements few and far between, Ibrahim was unable to support his family and felt compelled to return to the United States. When he left South Africa, in 1969, the Herald mourned the departure of „The Genius We Rejected.“ He told the paper that he was going back to New York, „where the only people who can understand my music live.“[74] In an interview with Drum, he linked his rejection by coloured audiences to their failure to come to terms with their own identity. „[T]here have been very few concerts where I have been able to allow myself complete freedom in communicating with those who have come to hear me,“ he said. „In order to understand and appreciate my message,“ coloured people had to „look within themselves and understand their own consciousness and the reason for their being. Once over this hurdle, appreciation of what I play becomes the next natural step.“ He contrasted the situation that he had found in Cape Town to that which he had experienced in New York. In the United States, the suffering of African-Americans „gave rise to some of the most beautiful blues music in the world….“ In South Africa, however, „there has been no reaction musically to our oppression. The local compositions reflect the character of the people–they are shallow, empty, lacking in sincerity and completely commercialized.“[75] Less than a year and a half after declaring that „There’s nothing out there. Everything’s here,“ Ibrahim was gone.

[74]. „Genius We Rejected,“ p. 9. [Emphasis in original.]

[75]. „Dollar’s Farewell.“In den frühen 70er Jahren kehrte er vorübergehend zurück und nahm erstmals direkten Kontakt mit Rashid Vally auf. Vally – der im südafrikanischen Klassifikationsschema als Inder galt – führte in Johannesburg einen kleinen Plattenladen, in dem sich Menschen aller Rassen und Hautfarben trafen. Ibrahim bat Vally, ihn aufzunehmen; im Oktober 1971 entstanden zwei Alben, die auf dem Label Soultown erschienen (später in auch auf Vallys The Sun Label, ebenso wie auf dem südafrikanischen Label Roots und – im Falle des Albums mit Kippie leider unvollständig – bei Kaz und Camden auf LP und CD).

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2711726-1329785777.jpeg.jpg)

Dollar Brand + 3 with Kippie Moeketsi (Soultown (SA)KRS113)

Kippie Moeketsi (as) Dollar Brand (p) Victor Ntoni (b) Nelson Magwaza (d)

Johannesburg, October 1971African Sun *

Bra Joe from Kilimanjaro *

Old Folks

Rolling *

You Are Too Beautiful

Memories of You *Notes :

Moeketsi’s name was mis-spelt „Moketsi“ on the original LP cover

All titles also on The Sun SRK786142, Roots ROTH118.

*) also on Kaz LP102, Kaz CD102, Century (Jap)25ED-6037(CD) and Camden CDN1007, all titled „African Sun“.

There’s also an entry for this in some discographies as from 1961 and with unknown bassist/drummer.Leider kenne ich von diesem Album bisher erst die vier Stücke, die auf der Kaz-CD zu finden sind – die CD gehört allerdings seit ich 14 oder 15 bin zu meinen liebsten Jazz-CDs, gerade auch wegen dieser vier grossartigen Stücke mit Kippie Moeketsi, von dem es viel zu wenige Aufnahmen gibt!

Brands Musik bewegt sich hier irgendwo zwischen US-Jazz und afrikanichen Einflüssen, er ist sozusagen not quite there yet, aber auf dem besten Weg. Kippies Altspiel ist unglaublich expressiv, wenn man das hier gehört hat, dann steht auch Dudu Pukwana nicht mehr ganz so alleine da, denn Kippie, der – zumindest musikalisch – eine Generation älter war, war mit Sicherheit DER zentrale Einfluss, als der 13 Jahre jüngere Pukwana begann, Saxophon zu spielen (zwei frühe Aufnahmen von Kippie finden sich auf dieser Compilation, die hier in den letzten Jahre hie und da billig zu finden war).

Das grosse Highlight der vier Stücke ist wohl der Standard „Memories of You“, den Kippie sich hier komplett aneignet – eine unglaubliche Interpretation, die mich jedesmal wieder berührt!

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-878131-1532799269-7360.jpeg.jpg)

Peace (Soultown (SA)KRS110)

Dollar Brand (p) Victor Ntoni (b) Nelson Magwaza (d)

South Africa, prob. Johannesburg, October 1971Shrimp Boats

Salaam (Peace)

Cherry

Tintinyana

Just a Song

Little BoyNotes :

All titles also on The Sun SRK 178637, Roots (SA)ROTH123.

All titles also on Kaz LP103, Kaz CD103 and Camden CDN1009, all titled „Tintinyana“.Auch auf den Trio-Stücken wir die Vermischung von Jazz und afrikanischer Musik weitergetrieben. Die Stücke stammen zumeist aus Ibrahims Feder, bloss der Walzer „Shrimp Boy“ (von Paul Mason Howard und Paul Weston) und „Just a Song“ (hier findet man bloss Hinweise auf das gleichnamige Stück des Traffic-Gitarristen, keine Ahnung, was das für ein Stück ist, das Ibrahim hier spielt) stammen nicht aus Ibrahims Feder.

Kontrabassist Ntoni und Drummer Magwaza begleiten Ibrahim swingend und recht leicht – diese Leichtigkeit fehlt auf den meisten frühen modernen Jazz Aufnahmen, die ich bisher aus Südafrika kenne (was auch das durchaus hörenswerte „Verse 1“ oder die frühen 1964er Aufnahmen der Blue Notes etwas clumsy macht). Auf „Tintinyana“ sind alle sechs Stücke des Albums enthalten, in zwei Hälften, die jeweils von einem langen späteren Stück eröffnet werden. Das erste Trio-Stück ist das grossartige 3/4 (oder 6/8?) Stück „Tintinyana“ präsentiert den rollenden Piano-Stil, den Brand in jenen Jahren pflegte (und der auch schon auf „Rolling“ und „Bra Joe from Kilimanjaro“ mit Moeketsi zu hören gewesen ist). Solistisch ist das alles recht unspektakulär, was Brand hier spielt, aber er prägt die Musik absolut, setzt die Grooves, sorgt für einen satten Klang… und manches klingt wohl einfacher, als es ist. Bei „Little Boy“ schleichen sich dann jazzfremde Rhythmen in den Drums ein, sehr fein gespielt von Magwaza, während Ibrahim mit seiner linken Hand den Boden legt, ergänzt von Ntonis agilem Bass, und darüber ein lebendiges Solo spielt, das stark von Repetition und Variation einfacher Figuren lebt. „Cherry“ ist dann schon einer der „Hits“ von Brand, den er bis heute immer wieder in seine langen Improvisationen einflicht, eine Erkennungsmelodie gewissermassen. „Salaam“ ist ein kurzes Solo, sehr meditativ, auch das geht in eine Richtung, wie sie Ibrahim bis heute pflegt. „Shrimp Boats“ ist ein langes, swingendes Stück über einen leichten 3/4-Beat, und „Just a Song“ ein lyrisches Stück, das zwischen langsamem Rubato und schnelleren Passagen in Time abwechselt. Ibrahims Piano klingt hier streckenweise schon ein wenig wie auf den späteren Aufnahmen, die ab 1974 entstanden, als er für längere Zeit nach Südafrika zurückkehrte. Doch davon später mehr…

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba -

Schlagwörter: Abdullah Ibrahim, Dollar Brand, Jazz, South African Jazz

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.