Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Enja Records › Antwort auf: Enja Records

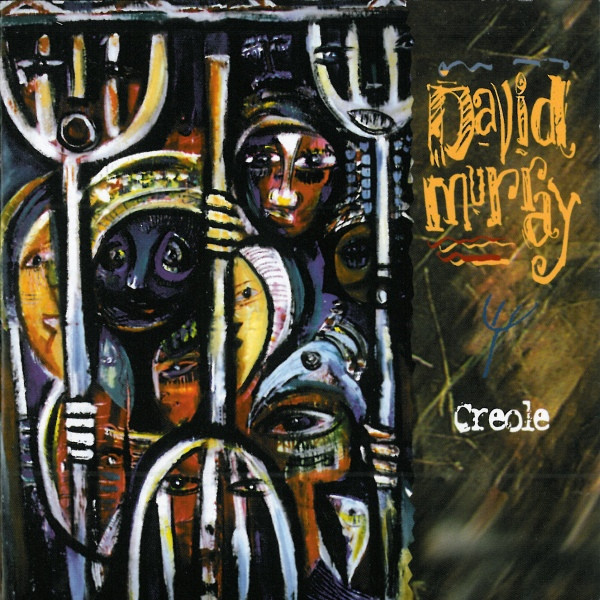

David Murray – Creole Project | Aufgenommen am 19. und 20. Oktober 1997 in Guadeloupe und später für Justin Time und Enja in den Sound On Sound Studios in NYC abgemischt. Als Produzent zeichnete Murray selbst. Mir ist das Album erst vor relativ kurzem in die Hände gekommen: ich habe es gekauft, als wir es hier im Forum ein ein paar Jahren mal davon hatte, an den Kontext kann ich mich nicht erinnern (bei Discogs steht, ich hätte es vor 4 Jahren meiner Sammlung hinzugefügt, d.h. noch vor der 90er-Strecke – ich habe die Enja-Ausgabe mit „Project“ als Zusatz, finde davon aber kein gutes hier verwendbares Bild). @redbeansandrice hat hier schön beschrieben, was es zu hören gibt:

neulich, als es um vielgehörte Enja Alben ging, hatte ich das hier völlig vergessen… produziert von Murray selbst, sowohl bei Justintime als auch Enja erschienen… abgebildet ist die deutsche Version, die man am etwas anderen Albumtitel erkennt, Creole Project statt Creole… das Konzept ist genauso ambitioniert wie einfach und fast idiotensicher, Murray fährt mit einer fantastischen Band (James Newton, DD Jackson, Ray Drummond, Billy Hart) nach Guadeloupe und nimmt da für zwei Tage mit lokalen Musikern auf… das Programm besteht aus Treffen mit der örtlichen Jazzszene, dem Flötisten Max Cilla, dem Gitarristen Gerard Lockel und einigen Perkussionisten, zum Teil in eher jazzigen Tracks, zum Beispiel einem tollen Duett von Murray und Lockel, zum Teil in Songs des Liedermachers Teofilo Chantre, die so ein bisschen mehr Lokalkolorit/Urlaubsstimmung schaffen… (also: ich bild mir ein, dass das quasi die Lieder sind, die man dort im Radio hört) Flöte/Tenor-Frontlines mag ich sowieso, Murray hat tolle Momente, genu wie DD Jackson… und dadurch, dass es ziemlich abwechslungsreich ist – und dabei trotzdem als ganzes zusammenhängt – sind auch die 60 Minuten nicht zu viel… macht schon Sinn, dass mir das Mal so gefallen hat. Ob das jetzt wirklich ein Enja Album ist… immerhin hat sich irgendwer für das Wort „Project“ im Albumtitel starkgemacht…

Mir gefällt das auch sehr gut, das Programm ist abwechslungsreich, Murrays Band in Form (Hart glänzt mit ungewöhnlichen Beats), der Leader hat Spass in freieren Gefilden ebenso wie im Material aus Guadeloupe („Flor Na Pau“ von Chantre wäre in einer instrumentalen Version auf „Lucky Four“ auch nicht fehl am Platz gewesen), in „Guadeloupe Sunrise“ gibt’s das erste Duo mit dem lokalen Gitarristen (mit „Guadeloupe After Dark“ folgt gegen Ende des Albums ein zweites), im folgenden „Soma Tour“ sind nach dem Leader die Flöten von Max Cilla und James Newton im Duett zu hören. Newton hören zu können ist ja eh ein viel zu seltener Genuss (fickt euch, Beastie Boys, fickt euch hart!) und er ist hier recht prominent. Ob er oder Cilla auf „Gansavn’n“ (komponiert von Kiavue) zu hören ist, ist mir nicht ganz klar, aber auf „Mona“ ist’s dann sicher wieder Newton. Ein echt schönes Album!

Das komplette Line-Up: David Murray (ts, bcl), James Newton (fl), D.D. Jackson (p), Ray Drummond (b) und Billy Jabali Hart (d) treffen auf: Klod Kiavue (perc, ka drum, voc), Max Cilla (flute des mornes), Gérard Lockel (g), François Landreseau (lead voc auf „Savon de Toilette“, ka drum) und Michel Cilla (dibass drum, voc). „Gwo ka“ steht für „grosse Trommel“ (hier im Line-Up „ka drum“), die Suche nach der „dibass drum“ ist etwas schwieriger, aber hier finde ich einen kurzen frz. Artikel über einen der letzten, der auf Martinique die „tanbou di bas“ (auch d’bas) herstellt und da gibt es unten auch ein Foto, auf dem er sie spielt:

https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/martinique/schoelcher/raphael-paquit-est-un-passionne-de-tambours-dont-le-traditionnel-tanbou-di-bas-1395870.html

(CN eher nichts für Vegetarier*inner, Veganer*innen und Freund*innen niedlicher Jungtiere – das wichtigste daraus zur Herstellung: fürs Fell braucht man die Haut von Zicklein, die strapazierbar und fein sei, die Haut wird feucht gemacht, dann zwischen zwei Metallkreisen eingespannt, justiert bis sie gut klingt, mit einem Strick festgezurrt und dann auf den Körper der Trommel gesetzt.)

Die Bedeutung der Gwo ka scheint kaum zu überschätzen zu sein – bei redbullmusicacademy.com gibt es einen Text von 2017:

Gwo ka is an artistic movement, comprising lyrics, dance and music, which made it onto UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014, but which was born in the 17th century. It is represented by the “ka” drum that slaves made from barrels destined for the transport of goods preserved in brine. More than just a simple instrument, the “ka” was also used to announce clandestine meetings or revolts against sugarcane plantation owners. Gwo ka was inevitably banned by the colonisers and criticised by the church, who denounced the “obscene” character of the dances and the excessive rum consumption associated with such events. There were also accusations that the tambouyés (tambourine players) were “spreading degeneracy among the Guadeloupean people.” Described as “old negro music” or “brown negro music” – “brown negroes” (nègres marrons) was the name given to slaves who managed to escape from the plantations – gwo ka was rarely celebrated on Guadeloupean soil. This music was exclusively played in rural areas, and was synonymous with the lowest social class. “Gwo ka is the blues of Guadeloupe,” says Richard.

It was only in the ’70s, when there was a push for independence, that gwo ka was finally granted a sliver of cultural recognition, with artists such as Germain Callixte, Kristèn Aigle and Serius Geoffroy bringing it back from oblivion. Vélo, a member of the band Akiyo – and founding member of the LKP some forty years later – modernised the Guadeloupean carnival with his group. The local carnival was always considered a form of catharsis and complaint against normal societal institutions, but Akiyo replaced the costumes made from satin, glitter and plastic jugs with traditional masks and gwo ka drums; they even wore khaki-coloured military helmets, traditionally symbols of colonial oppression. Another performer, Robert Loyson, a sugarcane planter, sang in a bathrobe when he spoke out about the troubles of his oppressed countrymen. Resentment towards gwo ka persisted, however. At the time, the ka master Gérard Pomer, who discovered the drum via his great uncle, a sugarcane cutter, was just a teenager. As soon as he began to play drums at the village market with his friends, “the police would turn up within five minutes and break the instruments we had made ourselves, right in front of our eyes.” Guy Conquet would go on to experience this, too. In 1971, this legend of gwo ka, nicknamed the “Bob Marley of Guadeloupe,” was arrested by the police for “acts of subversion” because he was singing during a strike organised on the sugarcane plantations of Baie-Mahault. One of his most famous songs, “Gwadloup malad’o,” was banned from the airwaves of official radio stations.

Den ganzen Text gibt es hier:

https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/09/gwoka-the-drums-of-discord

Im Wikipedia-Eintrag zu Gwo ka wird auch klar, dass Gitarrist Gérard Lockel auch als Musikologe wichtig war: Er unternahm mit seinem „Traité de Gwoka modên“ den ersten Versuch einer Einordnung der Musik aus Guadeloupe und verortete sie im Kontext afrikanischer Musiktraditionen, aber: „Paradoxically, under Lockel’s leadership, Gwoka was transformed from a participatory music played outdoors to a presentational music played on stage with European and North American instruments.“ (Dazu ist eine PhD Thesis von 2011 als Quelle angegeben.)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169: Pianistinnen im Trio, 1984–1993 – 13.01.2026, 22:00: #170 – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba