Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Count Basie › Antwort auf: Count Basie

Morris Levy von Roulette gab keine Ruhe, bis er die ganze „Gang“ auf seinem Label hatte: John Williams hatte er im Paket mit Basie dabei, Billy Eckstine kam 1959 zu Roulette, Sarah Vaughan folgte 1960-63 (dann kehrte sie zu Mercury zurück).

Was man bei Roulette und Birdland immer im Hinterkopf behalten muss: es war der Mob, der den Laden schmiss. Dazu gibt es auch eine schöne Geschichte in der Autobiographie von Basie:

The Midgets vs. The Bombers – or: Morris Levy beneath the bus

There was team spirit in each one of the sections, and it all added up to what was good for the band as a whole. Everybody wanted to make the band a success. So however this thing got started, it was all in fun, and that’s the way it stayed. But by the time of the Birdland tours, the band was also divided into two groups that were always challenging each other in the games we used to play on the road and in various places, games mainly like softball, which may have been how it got started.

Anyway, on one side there were the little guys like Joe Newman, Sonny Payne, Frank Wess, Frank Foster, Benny Powell, and so on; and they called themselves the Midgets. And the others, the big guys like Poopsie, Coker, Eddie Jones, and Bill Hughes, were known as the Bombers. … Usually the big guys would have to go with the Bombers, but naturally Lester insisted on being one of the Midgets. He was really too big to be a Midget, but he had to be with the underdogs, which was a joke, because the Midgets were the ones who were always coming out on top, beginning with softball and going right on through most of the other horsing around.

Well, Morris Levy was classified as a Bomber, and he was having a ball with all of the games and pranks, and when the tour went out to Kansas City, Morris went around to the novelty stores and bought up a supply of water pistols for the Bombers to attack the Midgets with. So they had the Midgets on the run, and then, according to Joe Newman, Sonny Payne found out where Morris had his supplies stashed, and the two of them stole them for the Midgets.

That’s what led to what happened to Morris in Kansas City. We were at the Municipal Auditorium, and several of us were standing near the bus talking with some local people—reporters, officials, and businessmen—if I remember correctly. And they were asking about who was in charge of the tour, and somebody said Morris Levy.

‚You mean, Morris Levy, the manager of Birdland, is traveling with the show?‘

‚That’s right.‘

‚And he’s in Kansas City right now?‘

‚Right now.‘

And right at that exact split second, we saw three or four of the Midgets heading in one direction, chasing a Bomber, shooting at him with water pistols. He was splitting, but they were gaining on him, and just as he got to about a few feet from where we were, he tried to make a fast cut to go around the bus and he slipped and ended up under it.

The people standing there talking to us just sort of glanced at what happened, and then turned right back and continued the conversation.

‚I’d like to meet him.‘

‚Well, that’s no problem. Here he is.‘

‚Where?‘

‚Right there under the bus.‘

‚Under the bus? What’s he doing under there?‘

‚The Midgets,‘ I said. ‚The Midgets ran him under there. They were after him.‘

‚The Midgets? Who are they? Is this some kind of gag?‘

So I told them about the Midgets and the Bombers. But then when Morris came out from under the bus, it turned out that he had just had a serious accident. That fall had actually broken his arm. The minute the Birdland people back in New York were told about that, they started burning up the telephone wires to Kansas City, and Morris had to explain that it was all part of a game. Because as soon as he said that the Midgets were chasing him, they thought he was talking about a mob trying to cut in on the business.

‚The Midgets? Who the hell are the Midgets?‘

Morris had to explain fast. His business associates in Chicago were ready to put somebody on the next plane to Kansas City to help him take Care of the situation. But Morris said it was all in fun and the joke was on him.(„Good Morning Blues,“ p. 316f.)

Als grosser Fan von Lambert, Hendricks & Ross war der Kauf des japanischen 2010er-Reissues von „Sing Along with Basie“ ein Muss für mich: die erste Gelegenheit, dieses Album überhaupt zu hören – und die CD lief seither häufig. Joe Williams kommt hier mit LH&R zusammen, und dazu diese vielleicht beste aller Basie-Bands inklusive dem Leader selbst am Klavier, bei insgesamt fünf Sessions im Mai, September und Oktober 1958. Es werden alte Favoriten wie „Tickle-Toe“ oder „Every Tub“ interpretiert, auch „Goin‘ to Chicago“ aus dem Repertoire von Williams‘ Vorgänger Jimmy Rushing, aber als Closer – mit Basie an de Orgel – auch das ganz neue „Li’l Darlin'“ von Neal Hefti. Die Worte hat – ausser für den „Going to Chicago Blues“ und den „Rusty Dusty Blues“ (J. Mayo Williams, 1943) – alle Jon Hendricks geschrieben. Dieses Album war vielleicht die einzige Möglichkeit, dem genialen Debut (LH&R „Sing a Song of Basie“, 1957 für ABC-Paramount aufgenommen) überhaupt noch etwas folgen zu lassen: die Basie-Band und ihren Sänger dazu holen (bzw. sich dazu einladen lassen). Von da an ging es dann im kleinen Format weiter, Gildo Mahones leitete das Backing-Trio, auf dem nächsten Album gastierte mit Harry „Sweets“ Edison aber auch wieder ein Basie-ite („The Hottest New Group in Jazz“, 1959 für Columbia aufgenommen). Und klar, Ike Isaacs, der Bassist, der im Juni 1962 bei Basie einsprang und danach auch die Europa-Tour (mit Louis Bellson am Schlagzeug) absolvierte, gehörte schon 1959 zur Begleitcombo von LH&R und ist auf deren drei ersten Columbia-Alben zu hören.

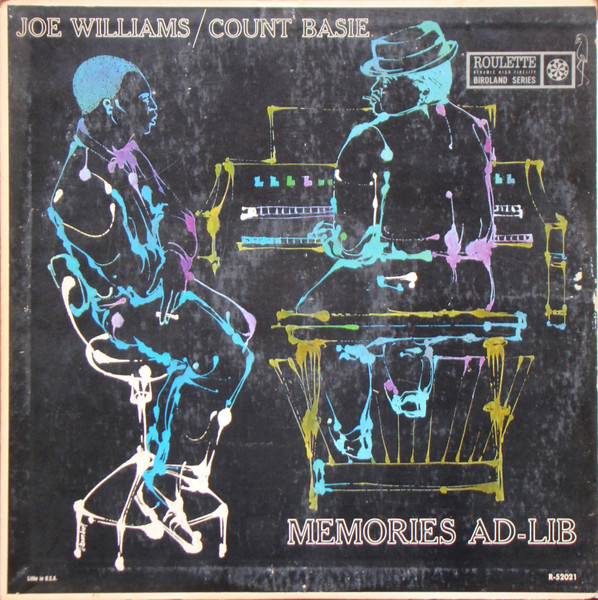

Joe Williams wurde von Morris Levy und Roulette – als Produzent der Alben agierte in der Regel Teddy Reig – gefördert. Schon ein Jahr vor dem ersten Album mit der ganzen Big Band entstand bei zwei Sessions im Oktober und einer dritten im Dezember 1958 das Album „Memories Ad-Lib“, auf dem Basie und Williams als Co-Leader geführt werden. Im Gegensatz zu den Aufnahmen mit der grossen Band kann Williams hier seine ganze Breite aufzeigen: von Fats Waller („Ain’t Misbehavin'“, „Honeysuckle Rose“) zu Balladen und Standards („All of Me“, „Memories of You“, „I’ll Always Be in Love with You“). Basie spielt hier fast nur die Orgel, Freddie Green ist an der Gitarre dabei, die Rhythmusgruppe vervollständigen George Duvivier (b) und eine der vergessen Legenden des Swing-Schlagzeugs, Jimmy Crawford von der Lunceford-Band (der noch bis 1980 lebte). Auf „If I Could Be with You“ und „Sometimes I’m Happy“ ist die Trompete von Harry „Sweets“ Edison zu hören – mit Dämpfer umgarnt er die Stimme von Williams, der in exzellenter Form ist. In „The One I Love Belongs to Somebody Else“ gibt es eins von Freddie Greens raren Soli zu hören – das streckenweise eher ein Dialog mit Basies Orgel ist.

Jimmy Crawford ca. 1946-48 im Studio mit Frankie Laine (Foto: William P. Gottlieb)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba