Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Wildflowers – New York Jazz Loft Sessions der Siebzigerjahre

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Ein Text und eine Playlist von Jim Allen zur Loft Jazz Szene:

https://daily.bandcamp.com/lists/loft-jazz-listEin paar Auszüge:

“You always have so-called ‘mainstream’ stuff happening,” says Wadada Leo Smith pragmatically. “That’s just the bandwidth of the commercial zone. You have it in every type of music.” Then the sagacious, 81-year-old trumpet innovator slows his speech for emphasis, adding dramatic punctuation with increasing pauses as his concepts expand. “Because those things are there—and you’re not part of them—then you have to build your own reality. And that reality is not a protest against—but it is something for—in this case, for ourselves.”

That’s how Smith describes the origins of the loft music scene that arose in 1970s New York City, a DIY network of literally homegrown venues created by and for musicians who transcended the conventions of jazz—even the term itself. “It’s an imposed name on a vast variety of music,” says guitarist Michael Gregory Jackson. “No one wanted to be put into a box and called a jazz musician.”

[…]

In the pre-gentrification ‘70s, much of Manhattan’s southerly section was a textbook example of urban blight. But that’s what made it possible for musicians to occupy loft spaces on the cheap. “I would walk down the street,” remembers Jackson of going to loft gigs with saxman Oliver Lake’s band. “It looked like it had been bombed. There was rubble and bricks, and it was pretty much a mess back then. New York was not the safest place.” Those conditions allowed for an upside, though. “It definitely wasn’t fully owned by corporations yet. People were able to afford to live there and do artistic things…it was inspirational.”

The scene wasn’t strictly limited to lofts. Galleries, storefronts, and former warehouses and industrial spaces all filled the need. The musicians lived, rehearsed, performed, and recorded in these places. In 1970, at 24 Bond St., a block from where CBGB would eventually operate, onetime Miles Davis saxophonist Sam Rivers and his wife Beatrice turned their home into Studio Rivbea, one of the circuit’s hottest hubs. “It was a beautiful spot with great vibrations,” says Smith. “People who came there had deep respect and love for the music. They came there to hear music, not to be part of some social scene. And afterwards they engaged with the artists, which is a perfect setting.” Another vital spot was Ali’s Alley, which began in 1973 when former John Coltrane drummer Rashied Ali transformed his 77 Greene St. home into a club, a recording studio, and the headquarters for his own label, Survival Records.

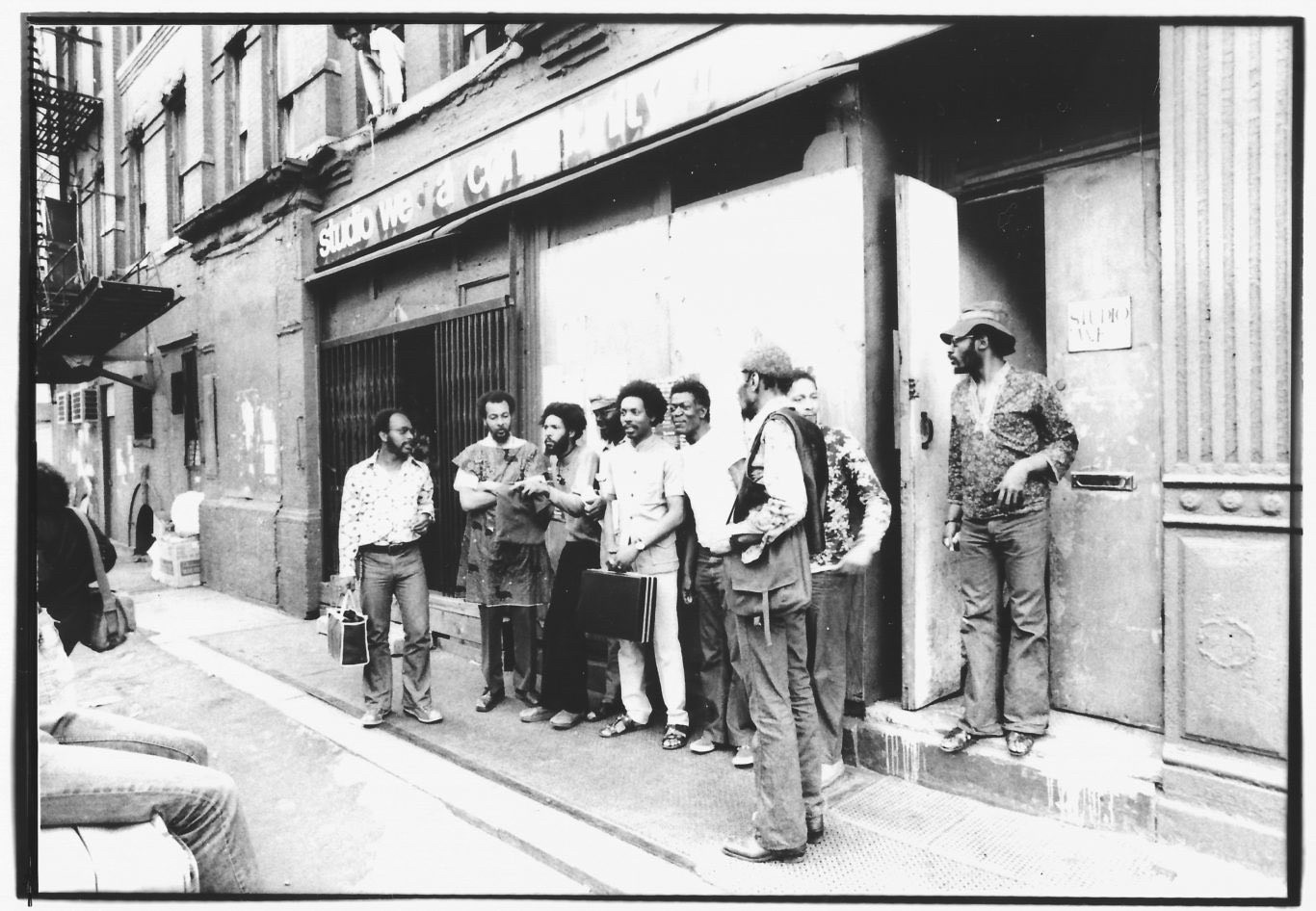

Many more proliferated throughout the decade. Trumpeter James DuBois and bassist/percussionist Juma Sultan were in on the action early with Studio We at 193 Eldridge St. Singer Joe Lee Wilson had The Ladies Fort on Bond St., a block away from Rivbea. Drummer Warren Smith started Studio WIS in Chelsea. Dave Brubeck’s sons Danny and Chris ran Environ in Soho. Saxophonist David Murray and writer/then-drummer Stanley Crouch had Studio Infinity on the Bowery. Theater director Ellen Stewart ran long-standing theatrical/musical space La MaMa in the East Village. Record producer Verna Gillis had Soundscape, a Midtown outlier on W. 52nd St. And there were scads of others.

[…]

The communal vibe between musicians, writers, and other artists helped keep everything connected. “It wasn’t ‘Show up to the gig, play, and leave,’” says Jackson. “This was a community. That kind of stemmed from the workshop concept that came out of Chicago and St. Louis. You could grow, and it was a nurturing situation. We weren’t having cutting contests [instrumental showdowns] or anything like that. People were very supportive and very open. I was very young and for me it was an affirmation to really be myself. That’s what I got from that scene, an inspiration from these brilliant people—Oliver, Julius, [Anthony] Braxton, David Murray, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Davis, Baikida Carroll, Olu Dara, Phillip Wilson, James Newton, Jessica Hagedorn, Ntozake Shange, Thulani Davis, Butch Morris.”

There was never a loft jazz aesthetic. The thing these wildly varied artists had in common was a willingness to take things someplace singular and unexpected, a quality the settings encouraged. “It was an area in which one could explore their musical vision,” says Smith. “When you’re not boundaried,” adds Jackson, “that allows freedom of thought, freedom of expression, freedom of individuality.”

[…]

“Probably the culmination of that was the Wildflowers series,” says Jackson. The cult-classic five-volume series of live albums was recorded in 1976 at Rivbea as part of a multi-day festival and released the following year on Casablanca Records, home of Kiss and Donna Summer. It gave artists like Lake, Jackson, Rivers, and the rest of the usual suspects a wider audience than ever before.

[…]

New avant-garde performance spaces like The Knitting Factory and The Kitchen were cropping up, but they were aided by the kind of grants and funding that weren’t in the cards for the lofts. “I don’t believe that was available for Ali and all those guys,” says Smith. “It’s a factor that involves how America looks at power and independence. If you go deeper into that, you have to start looking at how race factors into how venues are established and sustained.”

Ultimately, the loft scene was too good to last. But four decades later, Jackson, Smith, Henry Threadgill, David Murray, Oliver Lake, and other bright lights of that circuit are still creating commanding, exploratory sounds. And that’s due in large part to the grounding they got in the loft era. “I consider that a renaissance period,” says Jackson. “For me it was a family like I didn’t have. It was a place where I could truly develop into who I really am. All these gifts I received just being around these luminous individuals, it remains in me to this day.”

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #165: 9.9., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaHighlights von Rolling-Stone.deCourtney Love: „Kurt wollte sich jeden Tag umbringen“

Beatles-Hit „She Loves You“: Anfang der „Beatlemania“

Oscars: Alle „Bester Film“-Gewinner von 1970 bis 2025 im Ranking

7 Bands, die (fast) so gut sind wie Deep Purple

Wieso „Schuld war nur der Bossa Nova“ auf dem Index landete

Die 22 fiesesten „Stromberg“-Sprüche: Büro kann die Hölle sein!

Werbung@gypsy-tail-wind: Danke dafür.

Ted Daniel, Milford Graves, Frank Lowe, Juma Sultan, Noah Howard, James DuBoise, unknown, Sam Rivers, & Ali Abuwi; outside Studio We, 193 Eldridge Street, NYC, 1973 (Foto: Thierry Trombert)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #165: 9.9., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba -

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.