Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Albert Ayler

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Hm, hab die CD nicht grad bei Hand, aber „thee“ macht für eine Predigt schon mehr Sinn als „he“, nicht?

Und ja klar mit dem „holy spirit“ und „holy ghost“, heisst ja auch beides „heiliger Geist“ :lol:

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaHighlights von Rolling-Stone.deTodesursache von Jimi Hendrix: Wie starb der legendäre Gitarrist?

Die letzten Stunden im Leben von Amy Winehouse

Joe Strummer von The Clash: Dies ist die Todesursache der Punk-Ikone

Johnny Cash: Leben und Tod einer Country-Legende

Neu auf Disney+: Die Film- und Serien-Highlights im März

Amazon Prime Video: Die wichtigsten Neuerscheinungen im März

Werbunggypsy tail windHm, hab die CD nicht grad bei Hand, aber „thee“ macht für eine Predigt schon mehr Sinn als „he“, nicht?

ja, aber ich find es vom hören her eigentlich recht eindeutig (er sagt es ja auch oft genug)

--

.redbeansandriceja, aber ich find es vom hören her eigentlich recht eindeutig (er sagt es ja auch oft genug)

Hm… es klingt schon eher wie „he“, beziehungsweise nach „fear ‚ee not“ mit sowas verschlucktem davor, das ich eben automatisch als „thee“ hörte, einfach weil’s mehr Sinn ergibt.

Und eigentlicht wollte ich jetzt mit den 1969er Sessions weitermachen, aber der Groove von Purdie auf „Thank God for Women“ ist so verdammt geil, muss zuerst nochmal diese Demos hören (den [blues] am Ende auch nochmal… den hörte ich damals vorab auf einem Wire Tapper)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbagypsy tail windHm… es klingt schon eher wie „he“, beziehungsweise nach „fear ‚ee not“ mit sowas verschlucktem davor, das ich eben automatisch als „thee“ hörte, einfach weil’s mehr Sinn ergibt.

Wieso das?

--

Ohne Musik ist alles Leben ein Irrtum.nail75Wieso das?

Weil in einer Predigt die zweite Person und der altmodische Gestus des „thee“ besser passt als die dritte Person. Aber ist ja am Ende nicht so wichtig.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaThe blindfold test is a peculiar institution, promoted by Downbeat and critic Leonard Feather, in which records by unknown artists are played for someone, usually a famous musician, to elicit the truthful response that anonymity should encourage. It is quite common for the interviewee to embarrass him or herself by failing to recognize the work of friends, proclaimed influences, etc. During the late 1960’s controversy regarding free jazz and Albert Ayler, his music was sometimes included to get the reactions of those who Feather considered „real jazz musicians“ to this bizarre new music.

During his lifetime, 7 musicians heard Albert Ayler’s music in the Downbeat blindfold test. While predominantly mainstream saxophonists, they also included players who were based in Coltrane’s work: reedmen Sonny Simmons and Prince Lasha, and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty. Here are their reactions, in chronological order.

Die obige Einleitung stammt von Jeff L. Schwartz, der auch Passagen aus Down Beat zusammengestellt hat.

Quelle: http://www.reocities.com/jeff_l_schwartz/aacritics.html

Booker Ervin (regarding the 3-28-65 version of „Holy Ghost“): That was probably made in concert. It sounded like Albert Ayler, or somebody trying to imitate Albert Ayler. I’ve heard Albert Ayler play, and I’ve heard one record I really liked by him, The Spirits.

But this record I didn’t particularly like because the music gave me no feeling of direction or anything. I heard no arrangement. I just heard guys running up and down their instruments and making sounds. I don’t particularly like that. I don’t have anything against avant-garde-I like some of it that is good, and I’ve heard Albert Ayler play some good avant-garde. I’ve heard Coltrane play some things that I liked with Pharaoh Sanders. But this thing, I couldn’t make it.

I don’t know whether this was Albert Ayler with his brother. I haven’t heard his brother but once on a record. It sounded like Sunny Murray or someone trying to imitate Sunny Murray’s playing. The bass player, he just sounded like he was running his fingers across the keys. There’s got to be some sort of technique involved in what they’re doing, which I know.

I didn’t hear any form, but I have heard some of Albert Ayler’s music which had some form to it-if that was Albert Ayler.

I like him as a person, he’s a very beautiful cat. If that was him, I didn’t like that at all. The music had no direction-not to me. I’d give it one star.

Oliver Nelson (on the same recording): Of course, that was a very highly charged performance. I suppose this-the kind of music I just heard-would be typical of the new wave or whatever. It might be considered the jazz that’s replacing whatever it was that we were talking about with Basie a minute or so ago.

But I had a feeling that that must be a record that my producer must have produced-Bob Thiele-because I don’t know of anybody else who is doing it.

There was little melodic organization, but toward the end they did something very startling. They played the melody–did you hear it? And they tried to play it in unison, and the ending was conventional.

I found the cello player good, bass player good. The drummer played some figures that reminded me of the drummer who used to play with Diz when he had his big band. In fact, the tune reminded me of „Salt Peanuts“ a bit, and the drum thing-which I would imagine would be alien to the kind of music they were playing, because it was rhythmically stable.

If I have to object to anything about this music, it’s mainly lacking in texture, and naturally I would feel that way, being an orchestrator and arranger. The same intensities are used. It’s like using red, black, and maybe some other kind of crimson color related to red all the time, and not being aware that white or green or blue exist too.

As to form; well, everybody just plays. It was a live performance, and the audience seemed pleased. It’s too early to say too much about this, because out of all this, ah, I guess you would call it chaos-out of it, somebody is going to have enough talent to integrate whatever is happening with this kind of music. It’s almost like chance music, which a lot of composers in Europe and here are trying-where you don’t limit a player to anything, and as a result, everyone plays.

I heard a group in Denmark last year, John Tchicai and the trombone player Roswell Rudd, and sometimes it happened and sometimes it didn’t. But when it happened, it was marvelous. They started out with something, and it happened to be a good melodic idea, rhythmic idea, and they would elaborate on that, and after a while, they would get into things that sounded like, I guess… complete freedom but still related to an essential idea. John is one of the most mature players in this kind of music.

Give the cellist four stars, but I’d rather not rate the record as a whole.

James Moody (on „Our Prayer“ 12-18-66 version): That sounded rather like „No Place Like Home“ and that’s where they should have been. I have no comment on that. I really don’t understand it. Coltrane did so much with the chord thing, he knew his instrument, knew musically what was happening and he did it. Then he went to the so-called free form thing, and I could understand it because he went step by step, so I’d take it that he knew what he was doing. But a lot of other people are doing this, and I’d never heard them play before, except this new thing.

I guess I’m just old fashioned-I just like to swing and hear some changes in there. I’m busy trying to learn changes myself. I hadn’t heard this record before, but I had heard the group before, playing at Trane’s funeral, and I’m just a little bewildered. I’m not saying it’s bad and I’m not saying it’s good-I just don’t understand it.

I wouldn’t want to play like that, because I don’t get anything from it. I can’t give it any stars; I don’t dig it.

Sonny Simmons and Prince Lasha (tested together) (on „Change Has Come,“ 2-26-67 version): Sonny Simmons: Well, there was no question about that. It was unquestionably Albert Ayler and his brother. I’m not familiar with all the personnel in the rhythm section, but I am acquainted with one of the bass players: Bill Fowler, I think his name is. I don’t know the other bass player or the drummer-it’s not Sonny Murray. Also the violin player, I think he’s a European.

Overall I’d give them four stars for what they are doing, because I understand what they’re doing.

Prince Lasha: Yes, I recognized Albert Ayler and his brother, and I’ll follow along with that rating. It’s the new music; they are trying to recapture the sounds that have been in the atmosphere for centuries, and are trying to utilize them. It takes quite a bit of concentration for them to organize and unite to come under that theocratic movement of music together. This is why I like the arrangements, the writing-and the violin also.

Jerome Richardson (on „Bells“ 8-31-67 version): Well, what do you want me to say about that? It sounds like a club date tenor player trying to get into the jazz thing. I wonder what they were doing-I don’t know whether they were trying to fool somebody or not. If that was their version of avant garde, they’d better do a little listening.

It held nothing for me. They were playing a little line together, and it sounded as though they were trying to see what they could do with the little line. It’s true that some things of this type have come off, but I don’t think that came off.

I haven’t the slightest idea who it was. The tenor player, I could give a wild guess-I’d still guess it was Don Ellis‘ band again. I’ll give it one star for effort.

Jean-Luc Ponty (on „Love Cry“ 8-31-67): That, of course, is Albert Ayler. I don’t remember the name of the tune, but I’ve already heard it on the radio in France. I like this one particularly. I don’t like all the work of Albert Ayler, but I think he has much humor, and especially when I hear this tune, I enjoy it and it makes me happy.

Sometimes this music reminds me of when I was in a military band and we were joking (I played tenor sax then) playing military marches. Anyway, he took a hard direction. He is one of the rare musicians who broke all old tradition completely; harmony and structures. I’m speaking in general of this music.

On this particular track I like the sound-of Albert Ayler himself, of his brother on trumpet, and from the drummer and bassist too. I think it’s a very good general sound of the group. Four stars.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbatoll! aber das augerechnet oliver nelson so differenziert urteilt (mit einer würdigung von john tchicai am schluss!) und jerome richardson sich so aufregt, fand ich überraschend.

--

Nelson… man kann sagen was man will und von seiner Musik halten was man will, aber ich glaub der hat sehr, sehr viel gewusst und begriffen und hatte immer offene Ohren (auch wenn seine Arrangements für andere macnhmal anderes glauben lassen).

Bei Richardson hat mich sowieso ein wenig gewundert, dass man ihn in den späten 60ern interviewt hat. Klar, er hat mit der Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Big Band gespielt, aber sonst war er ja längst in den Studios verschwunden. Ich kann mir nicht vorstellen, dass man ihn in den Jahren als wichtigen Jazzmusiker wahrgenommen hat. (Tut man ja leider bis heute kaum.)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbagypsy tail windNelson… man kann sagen was man will und von seiner Musik halten was man will, aber ich glaub der hat sehr, sehr viel gewusst und begriffen und hatte immer offene Ohren (auch wenn seine Arrangements für andere macnhmal anderes glauben lassen).

das scheint mir auch so. das tollste an der BLUES AND THE ABSTRACT TRUTH fand ich ja immer seine eigenen soli – ich weiß aber nicht, ob und wenn ja wo er sonst noch mal so avantgardistisch als saxophonist unterwegs war…?

--

vorgartendas scheint mir auch so. das tollste an der BLUES AND THE ABSTRACT TRUTH fand ich ja immer seine eigenen soli – ich weiß aber nicht, ob und wenn ja wo er sonst noch mal so avantgardistisch als saxophonist unterwegs war…?

Kennst du die beiden früheren Alben mit Dolphy, Screamin‘ the Blues und (vor allem) Straight Ahead? Die sind toll… bin ja etwas enttäuscht von der Auswahl an Leuten, die Feather gefragt hat… jemanden wie Coleman Hawkins etwas hätt ich lieber gehört… und von Lasha/Simmons hätt ich gern den kompletten Test

--

.redbeansandriceund von Lasha/Simmons hätt ich gern den kompletten Test

Falls das was hilft:

Leonard Feather: Blindfold Test. Sonny Simmons/Prince Lasha, in: Down Beat, 35/10 (16 May 1968), p.

33 (BT: Albert Ayler: „Change Has Come“; Hubert Laws: „Miss Thing“; Ornette Coleman: „Poise“; Rolf

Kühn & Joachim Kühn: „Lunch Date“; Eric Dolphy: „The Madrif Speaks, the Panther Walks“; Bud Shank:

„Blues for Delilah“; Count Basie: „Jump for Johnny“)Hier noch das Cover der Ausgabe:

Edit: hier stehen aber andere Titelstories als oben sichtbar sind… seltsam.

--

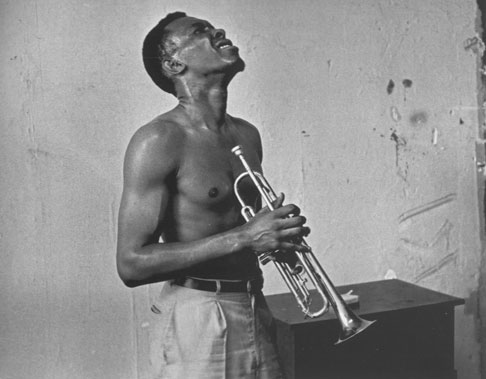

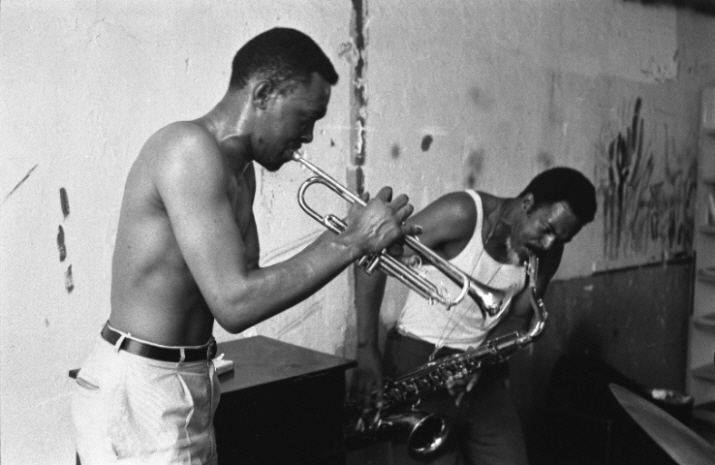

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaVermutlich 21. September 1968: Slugs‘, NYC – Don Ayler mit Arthur Jones (as), unknown (b), Muhammad Ali (d), sowie Albert Ayler (bagpipes)

11. Januar 1969: Town Hall, NYC – Don Ayler Sextet: Sam Rivers (ts), Richard Johnson (p), Richard Davis & unknown [Ibrahim Wahen?] (b), Muhammad Ali & unknown (d), sowie Albert Ayler (as/ts) [AUD rec, „Holy Ghost“ CD7]

26., 27. & 29. August 1969: Plaza Sound Studios [Impulse-Sessions für Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe (AS-9191) und The Last Album (AS-9208)]

Vermutlich 1970: Sirrah’s House, Cleveland – Ayler (ts), Jimmy Landers (g), Bobby Few (p)Zu Jimmy Landers: er leitete die Hausband in Gleason’s Musical Bar in Cleveland –

By the age of 15, Ayler’s reputation had spread beyond Church and school. Pearson formed a band known as Lloyd Pearson and the counts of Rhythm with himself on tenor and Ayler’s playing alto, and the two teenagers started to flex their muscles on competitive local jam sessions. Gleason’s Musical bar was the place where visiting musical acts would go to pick up sidemen, and sitting in with the house band, led by guitarist Jimmy Landers, was an important step. It was there that Ayler met Little Walter Jacobs, the harmonica player from Alexandria, Louisiana, whose unique chromatic work gained expression accompanying Muddy Waters. He played several small local clubs with him, then Walter took him on the road. Pearson was also in the band.

~ Valerie Wilmer: „Spiritual Unity“, Liner Notes zu Albert Ayler, „Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70), Revenant, ca. 2004, S. 13.

Das Programm Aylers wurde auch 1969 nicht dichter, im Gegenteil, seine Auftritte scheinen immer seltener geworden zu sein, in zwei Fällen war Don Ayler der Leader und Ayler gesellte sich zu dessen Gruppe, so auch am 11. Januar in der New Yorker Town Hall. In grauenhafter Qualität sind zwei über zehn minütige Stücke zu Beginn der siebten CD von „Holy Ghost“ zu hören: „Prophet John“ und „Judge Ye Not“, beides Originals von Don Ayler. Die Gruppe besteht aus Don Ayler (t), Albert Ayler (as – die Chronologie sagt ts), Sam Rivers (ts), Richard Johnson (p), Richard Davis & Ibrahim Wahen (die Chronologie sagt Davis & unknown) (b) und Rashieds Bruder Muhammad Ali (d).

Ben Young schreibt dazu:

Town Hall [Don Ayler]

The late ’60s were difficult times for Albert’s and Don’s relationship as brothers. Albert became involved in musical, professional, and living situations in which it was increasingly difficult for him to ask Don to take part. At what would have been the logical strong point for the younger brother to break away and expand his career, Don’s mental infirmity began to undercut his musical pursuits. But at the turn of 1969, indications arose that Don Ayler was attempting to do his own thing: occasional gigs as a leader at Slugs‘ and a record – still unreleased – for Jihad, from a time when he was living in Baraka’s basement in Newark. Contrary to the general assumption, he also stayed in limited touch with his brother. Albert had a role in some of Don’s shows, usually appearing as a guest on any instrument but the tenor saxophone.So it was (as audience member Don Cherry reminds us) for the nearly forgotten Don Ayler appearance at Town Hall on Disc 7. Don Ayler shared a bill with alto saxophonist Noah Howard’s sextet, both groups substituting copiously into the lineups announced in the concert programs. Don also invited Albert to perform a program that included several of the tunes Don had recently recorded for Jihad.

This is the last verifiable appearance of Albert and Don together, and certainly the last document there is of the two. It’s also the last known live recording of Ayler in the United States.

~ The Sessions, Liner Notes zu: Albert Ayler, „Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70), Revenant, ca. 2004, S. 163.

Die schwierige Beziehung von Albert und Donald Ayler haben wir schon angesprochen in der Diskussion, Val Wilmer schreibt in ihrem einleitenden biographischen Essay zum „Holy Ghost“-Buch folgendes:

There were indications that Ayler was emotionally disturbed at the time of his death. Donald Ayler was one of New York’s casualties, and apparently Albert blamed himself for the breakdown he suffered in 1968 when their musical association ended. Back at home in Cleveland, Donald gradually recovered his health and put on weight. His trumpet, though, lay on the table out of its case, gathering dust and totally ignored. Six years later, he started playing again, sometimes with Mustafa Abdul Rahim and occasionally with Al Rollins, a tenor saxophonist who owns a Cleveland barbershop, yet wherever possible, he would avoid referring to his brother by name.

~ Val Wilmer: „Spiritual Unity“, Liner Notes zu: Albert Ayler, „Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70), Revenant, ca. 2004, S. 128.

Hier ist die alte Geschichte, in der die gelegentliche Zusammenarbeit, die mindestens bis ins Frühjahr 1969 anhielt, ignoriert wurde, aber ich will Wilmers Ansicht im grossen ganzen keineswegs anzweifeln.

(Photo: Larry Fink)Die beiden Stücke vom Januar 1969 sind lärmig und es ist schwierig, viel zu erkennen. Muhammad Ali trommelt dichter als sein Bruder, mit weniger Variantenreichtum. Von den Bässen und dem Klavier ist kaum etwas zu hören, die Saxophone lassen sich schwer auseinanderhalten – im Thema von „Prophet John“ scheint Rivers eine Art tiefe zweite Stimme zu Don Aylers Trompetenphrase zu spielen, einer einfachen Melodie, die schier endlos repetiert wird. Albert Ayler wirft mit dem Alt wilde Schreie ein, es ist sein ungezügeltes Spiel, das dem Thema eine gewisse Spannung verleiht. Don geht dann in sein Solo über, auch das lebt von wenigen Ideen, die wiederholt und gedreht und mit den bekannten flächig hingeschmierten Glissandi verknüpft werden, und schon bald taucht auch die Phrase des Themas wieder auf und wird erneut endlos repetiert. Rivers (?) beginnt zu solieren, ist aber kaum zu hören, während Ayler (?) weiterhin seine Einwürfe macht. Dann übernimmt wohl Ayler mit dem Altsax, das dank der höheren Lage und Aylers riesigem Ton aus dem wilden Gebräu herauszustechen vermag, etwa um 4:40 herum beginnt ein eigentliches Solo, das sich vom Rest der Band klar abhebt und unglaublich intensiv wird – das kann eigentlich kein anderer als Albert Ayler sein! Nach diesem kathartischen Solo verlangsamt sich das Tempo, Rivers‘ Tenor ist prominent zu hören, während Don Ayler wieder mit dem Thema einsetzt.

Das zweite Stück, „Judge Ye Not“, beginnt als Hymne, irgendwo zwischen dem späten Coltrane und Albert Aylers Musik. Wieder tragen Trompete und Tenor die Melodie, während Aylers Altsax etwas freier ist und die beiden umspielt. Er bläst auch ein erstes Solo, sein Ton jubilierend, seine Phrasen weit und voller Vibrato (da ist wieder der Geist von Sidney Bechet und Al Sears und Johnny Hodges). Die Musik verdichtet sich dann, Don Ayler übernimmt den Lead in einer furiosen Passage, bevor die Intensität wieder etwas abflaut und die Musik zum Thema zurückbewegt. Nach etwa sieben Minuten scheint die Musik zu enden, die Bläser spielen langsame hymnische Linien, Muhammad Ali lässt die Drums donnern, dann setzt Richard Johnson mit einem Piano-Solo ein, während die Bläser ganz aussetzen. Alis Drums übertönen das Piano zunehmend und für die letzte Minute setzen die Bläser wieder ein mit ihrem hymnischen Spiel.

(Photo: Larry Fink)In Ergänzung zum obigen Post zu New Grass (hier) und mit Blick auf die folgenden Studio-Sessions vom August 1969, hier noch eine längere Passage von Jeff Schwartz (dessen Buch wurde oben wohl auch schon erwähnt? Es trägt den Titel „Albert Ayler: His Life and Music“ und kann >hier< gelesen werden). [QUOTE]It is likely, however, that the dominant influence on this, and Albert's following recordings, rather than the record company, was, as Call Cobbs said, Mary Parks, who used the stage name Mary Maria. Albert had become fascinated by her poetry and recorded it, singing himself, since he doubted that he would be allowed to use an unknown singer (Mary) in his band (Wilmer 1980: 108). Albert had brought Mary into his music, first by teaching her the saxophone, then by recording her words. For the next recording, she sang lead on many songs. The two of them would play their saxophones in Prospect Park, Brooklyn and were once nearly arrested for playing too loud. Mary also rehearsed with Call Cobbs, though not with any of the other band members (Wilmer 1980: 108) in the tradition of the big bands Cobbs had worked with and the blues bands of Ayler's past, which often had a music director, who saved the star the work of actually leading the band. While the remainder of Ayler's career has generally been written off as a sell-out, this is not the case. New Grass seems to be commercially motivated, but it is highly possible, in light of "To Mr. Jones, I Had a Vision," that Albert felt the need to expose his message to a wider audience than that for "experimental jazz." If Albert truly felt that he had heard Gabriel sound the last trumpet, signaling the coming apocalypse, then his move towards more conventional forms is wholly understandable. Regardless, New Grass is an extraordinary album, whatever genre one chooses to assign it to. Albert sings on most of the songs, not in the way he had on Love Cry and the Paris version of "Japan," but in the R&B idiom. His singing however, displays the phrasing he has acquired as a saxophonist, and abounds in quarter tones and irregular rhythms. His vocals bear the same relation to Otis Redding or Ray Charles that his saxophone playing does to King Curtis. The lyrics, by Mary Parks, are (as most critics have noted) not excellent poetry, however, they hold up as well as most rock or soul lyrics; to judge them as poetry is irrelevant and condescending, reminiscent of the old Steve Allen comedy routine, where he would recite, as if it were a poem, some classic rock song like "Be-Bop-A-Lula" or "Tutti Fruiti." Park's lyrics are rhythmically effective and gracefully communicate the spiritual concerns of "To Mr. Jones..." without being overbearing. The band sounds good, though Bill Folwell's approximation of funk bass occasionally sounds stiff next to Bernard Purdie's incomparable groove. Call Cobbs seems in his element, and contributes some truly interesting material, especially on "Sunwatcher," where he provides incredibly rich organ chords in the introduction. What most critics have ignored about Ayler's later recordings is that his saxophone sounds better than it has since Bells. In this new context Albert no longer feels that he has to limit his solos to a particular orchestral role and he utilizes the full spectrum of saxophone tonality for the first time since 1964. He plays "inside," "outside," and, in "Sunwatcher," even switches to ocarina for a chorus after his tenor solo has finished. Taken out of context, Albert's instrumental prowess would only become more apparent from this date on. In context, it would be casually dismissed, because most tunes featured vocals. In fact, New Grass was Ayler's only album to contain R&B music. His later records, while including many vocals by him and Mary, were solidly "Free Jazz." Aylers letzte Studio-Aufnahmen entstanden an drei Tagen Ende August 1969: [QUOTE]Albert Ayler (ts, voc) Bobby Few (p) Stafford James (b) Bill Folwell (el bg) Muhammad Ali (d) Mary Maria (Parks) (voc) Plaza Sound Studios, New York, August 26,1969 (studio record date) * Music is the Healing Force of the Universe (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) * A Man is Like a Tree (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) ** Again Comes The Rising Of The Sun (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) ** Desert Blood (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) Albert Ayler (ts, bagpipes, voc) Henry Vestine (g -4,6) Bobby Few (p) Stafford James (b) Bill Folwell (el bg) Muhammad Ali (d) Mary Maria (Parks) (voc) Plaza Sound Studios, New York, August 27,1969 (studio record date) * Masonic Inborn, part 1 (Albert Ayler) * Oh! Love of Life (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) * Island Harvest (Albert Ayler, Mary Parks) * Drudgery (Albert Ayler, Henry Vestine, Bill Folwell) ** All Love (Albert Ayler) ** Toiling (Albert Ayler, Henry Vestine, Bill Folwell) ** Birth Of Mirth (Albert Ayler) ** Water Music (Albert Ayler) *** Poetic Soul (Albert Ayler) *** Joining Forces (Albert Ayler, Henry Vestine, Bill Folwell) [I]Note: The information about the unreleased tracks is taken from the Jeff Schwartz biography. The Holy Ghost book states that “Ayler was also likely involved in an Aug. 28 overdub session.” Albert Ayler (ts, bagpipes, voc) Henry Vestine (g) Plaza Sound Studios, New York, August 29,1969 (studio record date) ** Untitled Duet (Albert Ayler. Henry Vestine) *) Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe Impulse AS-9191 **) The Last Album Impulse AS9208 ***) unreleased [IMG]http://image.allmusic.com/00/amg/cov200/drf700/f786/f78649ss2zg.jpg Die Musik dieser Sessions ist wieder klar Jazz, deutlich an Coltranes späte Aufnahmen angelehnt, die Rhythmusgruppe spielt dichte Texturen, Muhammad Alis Spiel gefällt mir hervorragend. Bobby Fews Piano bewegt sich irgendwo zwischen Alice Coltrane und Cecil Taylor, ist aber insgesamt nicht besonders prägend für die Musik. Überhaupt fällt auf, dass Aylers Bands gegen Ende mit eher schwächeren, weniger deutlich ausgeprägten musikalischen Persönlichkeiten bestückt waren. Er ist der Star, der sich begleiten lässt, viel Raum erhält neben ihm in erster Linie Mary Maria, deren Gesang auf vielen Stücken zu hören ist. Nach Schwartz' Einteilung ist das die erste von drei Gruppen von Stücken: "Music is the Healing Force of the Universe", "A Man is Like a Tree", "Again Comes the Rising of the Sun", "Desert Blood", "Oh! Love of Life" und "Island Harvest". Die zweite Gruppe sind Coltrane-geprägte instrumentale Stücke: "Birth of Mirth", "Masonic Inborn", "All Love" und "Water Music". Die dritte Gruppe dann sind die kontroversen Stücke dieser Session, die Zusammenarbeit mit dem [I]Canned Heat Gitarristen Henry Vestine: "Drudgery", "Toiling" und "Untitled Duet", das einzige Stück der letzten Session. [B]Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe beginnt mit dem Titelstück und dessen Präsentation von Aylers am Tenor, begleitet von den beiden Bässen, Alis dichten Rhythmen und den Akkorden Fews. Das Stück wird in einem fliessenden Beat präsentiert, Parks setzt dann ein mit dem Text - es wird mal wieder klar, dass die beiden (Parks und Ayler) nicht besonders geschickt sind darin, den Rhythmus der Sprache in den Rhythmus der Musik zu übertragen, der Gesang wirkt ziemlich linkisch. Ayler gesellt sich am Tenor dazu und übernimmt für ein kurzes Solo, dann begleitet er Parks in ihrer zweiten Passage. Es folgt ein zweites Tenorsolo, immer noch recht verhalten für Ayler, er bleibt fast durchwegs in der tiefen Lage, lässt seinen Ton growlen und heulen. Das Stück läuft weiter im Wechsel von Ayler und Parks und bleibt am Ende etwas unter den Erwartungen - es fehlt jedenfalls ein klares Distinktionsmerkmal, die Musik bleibt etwas glatt, da ist nichts, was wie bei "New Grass" Angriffsfläche aber auch Anlass zu Begeisterung bietet. "Masonic Inborn" ist mit über zwölf Minuten das längste Stück der Sessions, Ayler spielt Dudelsack, mittels [I]overdubs sogar zwei Stimmen zugleich. Das Tempo ist schneller, die Bässe von Folwell (im linken Kanal) und Stafford James (im rechten) bieten ein tolles Fundament, das ständig in Bewegung ist. Few legt darüber Ornamente, die allerdings wenig Biss haben (er ist aber auch im Mix fast ganz abgetötet, was sehr schade ist) und Ali hält sich ziemlich zurück. Aylers Dudelsackspiel macht Spass, klingt streckenweise fast wie ein Sopransax, aber da sind diese endlosen Singsang-Linien, die man auf dem Sopran so kaum hingekriegt hätte... die Musik wirkt auf mich allerdings ziemlich fahrig, wenig konzentriert. Nach dem Dudelsack folgt... ja was denn? Ein Bass-Solo? Nicht wirklich, eher begleitet die Rhythmusgruppe einfach weiter aber nichts geschieht, dann folgt eine Flöte (Ayler?), oder pfieft da jemand? Jemand zweites gesellt sich dazu, Ali verdichtet die Rhythmen ein wenig - sein Spiel ist überhaupt das beste an der Rhythmusgruppe. Few folgt dann mit einer Art Solo, das aber auch nicht richtig abheben will, dann doch noch die Bässe... Folwell greift immer mal wieder zum Bogen. Darüber tauchen Klänge auf, die ich nicht zuordnen kann, ein Harmonium, Pfeifen, Flöten, Geigen? Es fand ja anscheinend am 28. August eine Overdub-Session statt, vielleicht stammt das eine oder andere von dort? Jedenfalls folgt dann zum Ende nochmal Ayler am Dudelsack und jetzt dreht auch Few langsam auf (wäre er doch bloss bei seinem eigenen Solo schon wach gewesen!) - seltsames Stück, das aber durchaus hörenswert ist, allein wegen Aylers Dudelsack-Spiel! Die zweite Hälfte des Albums enthält dann vier kürzere Titel, zuerst "A Man Is Like a Tree", das dem Titelstück ändert: Ayler eröffnet in den tiefen Lagen am Tenor, dann folgt Parks mit ihrem nichtssagenden vertonten Gedicht ("A man is like a tree / that grows from the sea..."). Die Rubato-Begleitung ist allerdings sehr schön geraten, Ali trommelt sehr zurückhaltend, Folwell spielt mit dem Bogen. Dann setzt Aylers Tenor ein, fein zunächst, verhalten und melodisch wie in der Spirituals-Session von 1964 und wie ich vermute überaus vom ganz späten Coltrane geprägt. Es folgen zwei weitere Vocal-Nummern, "Oh! Love of Life" und "Island Harvest". Im ersten ist Ayler der Vokalist, öffnet aber zuerst wieder mit einem Tenor-Intro, hier kräftiger und kerniger intoniert, sein Ton reich an Obertönen. Sein Gesang wirkt allerdings sehr maniriert, die unbedarfte Frische und Direktheit seiner ersten Aufnahmen als Sänger/Vokalist vom Vorjahr ist verschwunden. Erwähnenswert ist aber erneut Alis tolle Begleitung. "Island Harvest" ist eine Mischung aus ein wenig Calypso (Aylers Spiel), Alice Coltrane'schen Teppichen (Few) und tollen Rhythmen (Ali und die Bässe). Für einmal überzeugt mich hier das meist, auch der Text ist dadurch, dass er eher eine Geschichte erzählt und nicht überdeutlich als Metapher und Lehrgedicht daherkommt, sehr viel erträglicher... und Parks Gesang ist stark und überzeugend. Das ganze ergibt einen ansprechenden Singsang, bei dem man auch in der Begleitung einiges entdecken kann. Ayler entpuppt sich als einfühlsamer Begleiter, der sein Tenor genau richtig dosiert. Few ist aber auch hier wieder etwas gar blumig. Zum Ende kommt Henry Vestine zum Einsatz und Bill Folwell wechselt zum E-Bass. "Drudgery" ist ein einfacher Blues in F in langsamem Tempo, Ali legt einen Shuffle-Beat, Vestine gesellt sich dazu, Ayler setzt nach einer Minute ein und spielt ein paar erdige Chorusse - wir haben schon in der Demo-Session vom Vorjahr gehört, dass Ayler mittlerweile ganz ordentlicher Blues spielen gelernt hat, das bestätigt sich hier erneut, sein Solo stünde jedem Texas Tenor gut an, die Begleitung wirkt aber ein wenig steif - Purdie hätte den Beat besser hingekriegt, Cobbs hätte besser gepasst (mit seinen [I]sanctified chords) als Few, Folwell war auch im Vorjahr schon das schwächste Glied der Kette. Das macht aber alles nichts, denn Ayler spielt sich eine Zone in diesem Stück, dem letzten überhaupt, das zu seinen Lebzeiten veröffentlicht wurde. (Um exakt zu sein: es war das letzte Stück auf dem letzten zu Lebzeiten veröffentlichten Tonträger - aber wenn die Session-Infos korrekt sind, dann war's eben auch die letzte Aufnahme, die zu Lebzeiten veröffentlicht wurde. Auf "The Last Album" folgte dann noch das "untitled duet" vom 29. August, und später erschienen auch die Aufnahmen aus Frankreich, die im Sommer 1970 entstanden). Henry Vestine überzeugt mit Gitarrenspiel, das typisch für den damaligen weissen psychedelischen Rock war. Seine Anwesenheit sorgte damals wohl für einigen Unmut. Robert Palmer schrieb 1978 die Liner Notes für [B]The Village Concerts (Impulse IA-9336-2), das Album, das den Rest der Aufnahmen verwertete, von denen auf [B]Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village (AS-9155) schon einige veröffentlicht worden waren. [QUOTE]I remember seeing Albert for the last time at the recording sessions for [B]Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe - August, 1969, fifteen months before his body was found floating in the East River. He was wearing a new fringed jacket, the kind rock musicians in bands like Moby Grape were wearing. The one musicians from the bands heard here who was still with him was bassist Bill Folwell, who also played Fender bass with rock groups and had followed Albert into an electric, jazz-rock soul area. The session I attended was strange. Folwell and guitarist Henry Vestine were interested in laying down the blues bottom Albert seemed to want, but the other musicians heard a freer, less structured sound. The tension in the music was manifested when Archie Shepp walked in, listened to a rough mix of the blues "Drudgery," and glanced at Vestine's long hair and pale face. "I'd have liked your playing a lot better," he told Henry, "if I hadn't seen what you looked like." ~ Robert Palmer [March 1978], Liner Notes zu: Albert Ayler - The Village Concerts (Impulse IA-9336-2), nachgedruckt in: Albert Ayler - Live in Greenwich Village: The Complete Impulse Recordings (IMP 22732, 2CD, 1998) [IMG]http://www.ayler.co.uk/assets/images/Lastalb.jpg [B]The Last Album erschien postum, es beginnt mit einem unbetitelten Duett von Vestine und Ayler am Dudelsack - das einzige Stück mit Vestine, das kein Blues ist. Diese Aufnahme gehört bestimmt zu den speziellsten in Aylers ganzem Werk - ich bin mir allerdings noch immer unsicher, ob sie gelungen ist oder nicht. Vestine spielt simpel, mit viel [I]reverb, Ayler legt darüber seine endlosen Dudelsack-Linien. Nach zwei Minuten setzt Ayler mal kurz aus und lässt Vestine einen Moment allein, dessen Spiel bricht auf und bleibt auch etwas offener, als Ayler wieder einsetzt. Die zweite Nummer ist "Again Comes the Rising Sun", in der ersten Session mit Parks aufgenommen. Sie rezitiert ihren Text mehr als sie ihn singt, die Band wechselt sich mit ihr ab. Das ganze wirkt auf mich gelungener als die meisten Stücke mit Parks, die auf "Music Is the Healing Force" gelandet sind. Das Stück hat Drive und zumindest Ayler und Ali spielen mit Gusto. "All Love" ist mit neun Minuten neben den beiden Nummern auf Seite A des ersten Albums und "Drudgery" die letzte lange Nummer der Sessions. Ayler ist klar in einer Coltrane'schen Stimmung, sein Ton ist verhältnismässig schlank, seine Linien meditativ, einfach, lyrisch. Die gestrichenen Bässe umgarnen ihn, Fews Piano klingt für einmal passend, Ali hält sich zurück, Ayler lässt sich viel Zeit für ein sehr schönes und ruhiges Solo. Die zweite Seite enthält wieder vier Stücke, als erstes den zweiten Blues mit Henry Vestine an der Gitarre und Folwell am Elektrischen Bass. Vestine ist erneut mittels [I]overdubs zweistimmit zu hören und soliert als erster, Ayler folgt und bläst ein weiteres grossartiges R&B-Tenorsolo. Mit "Desert Blood" folgt die zweite und letzte Vokal-Nummer des Albums, dieses Mal singt Ayler nach seinem Tenor-Intro über einen Rubato-Beat. Wieder wirkt sein Gesang ziemlich affektiert - zudem ist noch Begleitstimme druntergelegt, wohl auch Ayler selbst mittels [I]overdubs. Den Abschluss machen zwei weitere Coltrane-getränkte Instrumentalnummern, "Birth of Mirth" und "Water Music". Im ersten öffnet Ayler begleitet nur von Ali, spielt wieder am unteren Ende des Tenors, mit grossem reichem Ton dieses Mal, bis er um 0:35 wieder zum schmaleren Ton wechselt, der sein Spiel hier so stark an Coltrane gemahnen lässt. Die Linien sind aber typisch Ayler'scher Singsang. Die Rhythmusgruppe gefällt mir hier ziemlich gut, auch Few passt auf den kürzeren Instrumentalnummern recht gut (ist mir sowieso ein Rätsel, weshalb er sich so schlecht einfügt... vor ein paar Jahren hätte ich nie geglaubt, dass ich mir irgendwo Call Cobbs am Piano wünschen würde, aber ich bin überzeugt mit ihm hätten diese Sessions eine ganz andere Note gekriegt und möglicherweise eine, die sie spannender gemacht hätte, etwas abseits vom Coltrane-Sound und etwas unkonventioneller, schräger, mehr in die "Zirkus"-Richtung, die hier eben völlig abhanden gekommen ist, was ich ein wenig bedaure - auch das übrigens eine Regung, die ich vor ein paar Jahren kaum je erwartet hätte). "Water Music" ist eine Rubato-Hymne, Folwells gestrichener Bass spielt eine zweite Stimme zu Aylers Linien, James und Few legen den Boden, Ali setzt aus. Ein wunderschöner Abschluss, sehr lyrisch und introspektiv - und erneut stark an den ganz späten Coltrane gemahnend. Die Sessions lassen mich am Ende etwas ratlos zurück. Einiges ist toll, anderes schön, die Stücke mit Mary Maria sind eher misslungen, das beste von ihnen landete nicht auf dem damals erschienenen Album sondern auf dem nachgereichten, die beiden Ayler-Vocals sind der Tiefpunkt, die Instrumentals insgesamt sehr schön, man hätte aus ihnen allein (ohne jene mit Folwell, vielleicht mit dem Duett als Coda) ein Album machen können, das ähnlich wie das in den 90ern erschienen Coltrane-Album "Stellar Regions" gewirkt hätte... aber insgesamt sind das keine irgendwie hervor- oder herausragende Aufnahmen geworden - und ich kann nicht mal genau sagen, woran das liegt. Vielleicht an der eher schwachen Band? Few allein ist jedenfalls bestimmt nicht schuld, Ali hätte anders gekonnt, wenn er denn dazu aufgefordert worden wäre. Gut jedenfalls, dass im Juli 1970 nochmal ein paar Aufnahmen entstanden, denn diese hier wären ein ziemlich verhaltener Abschluss von Aylers kleinem aber bedeutenden Werk gewesen. Einen Review aus [I]Jazz Monthly (No. 186 - August, 1970) kann man >hier< nachlesen. Als Coda nochmal Robert Palmer aus der bereits zitierten Liner Notes: [QUOTE]Not too long ago I came across a recording made in the Louisiana State Mental Hospital in Jackson in 1959-60 (on the Arhoolie album [B]Country Negro Jam Session). The recording was taken during a music therapy session. one patient was alternately singing and blowing into a coke bottle, "with crowd," the album notes added, "banging sticks on wooden cylinders." The sound wasn't random though. It was the sound of music from the African rain forest, with the coke bottle player using a whooping technique common to the [I]hindewhou whistle players of the Pygmies and to some of the old Black country panpipe players in the Southern U.S. and other patients laying down crisp polyrhythms. Why was the only recording of this kind of music ever taken in the U.S. taken among black patients in a mental hospital? Does it have anything to do with the William Carlos Williams dictum that rock writer Peter Guralnick is always quoting: the pure products of America go crazy? Were the Aylers, Children of the Light, too pure to survive the social splintering and psychic untertow of the sixites? ~ Robert Palmer [March 1978], Liner Notes zu: Albert Ayler - The Village Concerts (Impulse IA-9336-2), nachgedruckt in: Albert Ayler - Live in Greenwich Village: The Complete Impulse Recordings (IMP 22732, 2CD, 1998)

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbar.i.p. Edward C. Ayler (1913-2011)

Etwas mehr in der News-Sektion der Ayler-Seite

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaGerade eingetrudelt:

http://www.jpc.de/jpcng/jazz/detail/-/art/Albert-Ayler-1936-1970-Spiritual-Unity-180g-Limited-Edition/hnum/8768781--

Free Jazz doesn't seem to care about getting paid, it sounds like truth. (Henry Rollins, Jan. 2013)icculus66Gerade eingetrudelt:

http://www.jpc.de/jpcng/jazz/detail/-/art/Albert-Ayler-1936-1970-Spiritual-Unity-180g-Limited-Edition/hnum/8768781Von ESP selbst? Das macht neugierig!

Wie ist die Qualität?Ich brauch bald mal die neue hatOLOGY CD!

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba -

Schlagwörter: Albert Ayler, Avantgarde, Donald Ayler, Free Jazz, Jazz

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.