Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Abbey Lincoln – That's Her! (1930–2010)

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Her utter individuality and intensely passionate delivery can leave an audience breathless with the tension of real drama. A slight, curling phrase is laden with significance, and the tone of her voice can signify hidden welts of emotion.

~ Peter Watrous, New York Times (1989)Her singing style was unique, a combined result of bold projection and expressive restraint. Because of her ability to inhabit the emotional dimensions of a song, she was often likened to Billie Holiday, her chief influence. But Ms. Lincoln had a deeper register and a darker tone, and her way with phrasing was more declarative.

~ Nate Chinen, New York Times (Nachruf, 2010)The only way I survive is to keep running my mouth. That’s how I keep from being wiped out, to keep expressing myself!

~ Abbey Lincoln im Gespräch mit Amiri Baraka („Abbey Lincoln“, in: „Digging“, 2009)

Abbey Lincoln kommt am 6. August 1930 als Anna Marie Wooldridge in Chicago zur Welt. Sie ist das zehnte von zwölf Kindern ihrer Eltern – insgesamt waren es 17, die anderen überlebten nicht. Lincolns Mutter „was the storyteller at home“ und hat ihr und ihren Geschwistern die Geschichte der Vorfahren erzählt, „in the autobiography that I’m writing, she wrote the first part of the book, 38 pages, and she told everything about — I mean, she told about the life that we lived before I was born“ (aus dem Gespräch, das 1996 für das Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master von Lincoln mit Sally Plaxson geführt wurde; von da stammen die nicht weiter belegten folgenden Zitate).

Der Grossvater mütterlicherseits, Charles Coffey, war bis zu seinem 14. Lebensjahr Sklave. Seine Mutter Ann Carter lebte wohl ihr ganzes Leben in Sklaverei und hatte vermutlich mindestens fünf Söhne: „Probably by an Irishman or a man who was like an octoroon. He was a slaver anyway, and when slavery was declared illegal, they sent her out of the house with a dime and a couple of blankets and they walked across Missouri and several of them had tent time and ragtime, like that.“ Die Grossmutter mütterlicherseits war wohl sehr jung („a child“), hatte 21 Kinder und war die Tochter eines freien Afro-Amerikaners und möglicherweise einer Native American Mutter.

Väterlicherseits scheint die Geschichte etwas einfacher zu sein: „… my father, she told us that his father was mostly Indian and he had some African, but his name was Wooldridge, which is an English name, right? And he went to jail for killing two men, and I think he served some time in Pittsburgh, and my grandmother’s name was Nellie, Nellie Wooldridge, who gave birth to my father, Alexander, who was an only child and a genius.“

Wohl weil die Mutter eifersüchtig ist, zieht die Familie aus den Suburbs von Chicago auf eine Farm auf dem Land. Als Anna Marie zehn ist, verlässt die Mutter den Vater. Im Gespräch von 1996 erzählt Lincoln, wie schwierig das war, dass sie im Winter fast verhungert wären. Sie erhalten dann staatliche Unterstützung und etwas Geld von den Brüdern, die während des zweiten Weltkriegs in die Armee gehen (der jüngste dient im Koreakrieg).

Gesungen und musiziert wurde zuhause nicht. Die Mutter sang in der Kirche (nicht im Chor), der Vater – so eine Erinnerung Lincolns im Gespräch von 1996 – hielt manchmal die jüngste Tochter im Arm und sang für sie. Lincoln fängt aber schon mit fünf Jahren an, auf dem Klavier herumzuspielen, zu singen, was sie in der Kirche aufschnappt, die Melodien nachzuspielen.

Im Haus auf dem Land gibt es ein handbetriebenes Victrola Grammophon, darauf hört Anne Marie mit 14 – kurz bevor sie nach Kalamazoo gezogen sind – Coleman Hawkins („Body and Soul“) und Billie Holiday: Platten, die ihre Schwester Betty Jean mitgebracht habe – „it changed my life hearing Billie Holliday’s sound […]. It was a sound that went right into my soul, in my spirit. She wasn’t trying for anything. It was just her sound“.

Der zeitliche Ablauf ist da nicht ganz klar: Lincoln sagt, die Mutter sei mit den Kindern nach Kalamazoo, nachdem sie ihren Mann verlassen hätte – da sei sie zehn gewesen. Aber später im Gespräch sagt sie, mit 14 sei sie nach Kalamazoo gekommen. Jedenfalls beginnt sie in der Zeit, die Musik zu hören, kennenzulernen, die für sie so wichtig werden sollte: „…when I got to Kalamazoo, I started to hear the singers when I was 14 on the radio. You could hear Billie, Ella, Sarah, the music, Dinah Washington, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. It wasn’t categorized as it is now. It was just music and there was space for all different forms. Nat Cole, Frank Sinatra and Johnny Ray, ‚Little White Plow That Cried.’There was plenty of room for the music then. I sang some of Rosemary Clooney’s songs. This is when I’m — well, this is around 23-24.“ (da wären wir dann bei ca. 12-14 Jahren).

In der High School in Kalamazoo – eine Schule mehrheitlich für weisse Jugendliche – ist Lincoln die Aussenseiterin:

I lived under the hill in the servants‘ quarters with my mother and my brothers and sisters, and it’s where I learned my — I established some individuality there since it wasn’t my school and they weren’t my playmates. I couldn’t afford to dress the way they did. They wore woolen skirts and woolen socks and woolen sweaters and I was making my own clothes out of things I’d find in the attic, you know. I’d put — I’d take my brothers‘ pants and make a skirt out of them. We couldn’t afford to go to the store and buy fabric, but I knew how to make something with my hands because I watched my mother and my sisters do it. We all knew how to make our own clothes and how to play with our hair. I came from a line of beautiful women.

In der Zeit fängt sie ernsthaft zu singen an:

I became a singer really in high school. It’s the only way I could stay in school because I really didn’t like school. I hated it with all my heart because they didn’t tell us anything about our ancestors. They told us we were a bunch of savages and I hated it. So, when I started singing once a year on the band follies, Mr. Chinnery was a wonderful man who encouraged me to think that I was a fine singer. It was his class and we had band follies every year. That’s where I saw Lionel Hampton and Ella Fitzgerald when I was about 17. So, I’d sing Ella’s „Sunday Kind of Love,“ the rendition, and I sang „Don’t Blame Me“ because I heard Sarah sing that and I sang Lena Horne’s „Stormy Weather.“

[…]

I failed in music. I failed in arts. I failed in home economics. The thing that kept me in school was that I could do this performance once a year with Mr. Chinnery. I was solo singer, and I didn’t know I was going to be a singer. It was just something to do. I didn’t want to leave school because I didn’t have anything to do and mama wouldn’t want me — she wouldn’t let me just sit around and — you know what I mean? I did it to please her.

Lincoln schliesst also die High School ab, lebt danach ein Jahr in Jackson, Michigan, und hat dort und auch schon davor in Kalamazoo erste Möglichkeiten, aufzutreten, besonders mit der Band von Benny Poole im Elks‘ Club in Jackson (hier ein Foto von 1973, das vermutlich den betreffenden Raum zeigt), aber sie kann auch bei Wardell Gray und Percy Mayfield einsteigen, hört Gene Ammons und andere Musiker bei Auftritten in Kalamazoo – meist Rhythm & Blues-Musiker. Über Jazz weiss sie damals nicht viel, ihre erste Begegnung mit Charlie Parker beschreibt Lincoln so: „It was so out that you couldn’t find your way in, right?“.

Mit zwanzig zieht sie nach Kalifornien zu ihrem Bruder, kann aber erst mit 21 in Clubs auftreten. Ein Agent mischelt ihr einen Gig:

The drummer would be a girl, the piano player would be a crazy man and me, and I’d stand and I’d sing songs and while the piano player played, I’d stand and try and look alive and move a little bit. It was like that.

In Roseburg, Oregon, Salt Lake City, Utah. A piano player. It was crucial for me to — he was a big man. He’d been in the Army, and Salt Lake City used to be a terrible city. You never saw any black people anywhere, and we opened the first night without a rehearsal. We’d never seen each other before and the agent had told the man who owned the club that we were an item, we were together, right? We really got over that first night and we went to get something to eat and we couldn’t get served anywhere. We went to maybe three places. The last place was a Chinese restaurant. We thought, oh, we can get some food here. This old Chinese lady stood at the back of the place where the kitchen was and screamed at us, hollered at us, „No service, no service,“ and all four of us, the piano player, his wife Mattie, Mattie the drummer, and me, we simply turned around and walked away and went back to the hotel hungry.

The next day, we had a rehearsal, and Walter got it off on me. He wasn’t brave enough to say to this Chinese woman who hollered at him, who do you think you’re talking to, he took it, one man with three women. So, he said to me, „Anna Marie, you’re singing the song wrong.“ I was singing „Let the Good Times Roll,“ Louis Jordan’s „Let the Good Times Roll,“ and I said to him, „Listen. You just play the piano and I’ll sing it.“ He said to me, „You hainty bitch. I’ll knock you down.“ I said, „No, you won’t.“ And he did. He got up off the piano and pushed me to the floor and I sprained my ankle. I couldn’t get up off the floor.Nach dem Vorfall sei sie für zwei Wochen mit Krücken aufgetreten – und hat das Ereignis in ein Gedicht eingebaut, das sie über ihr Leben geschrieben hat, als sie 1970 New York verlassen und wieder nach Kalifornien gezogen ist:

On Being Black

On the edge of his tongue he dared not speak father to mother, young and adultness going to and from school, it was spewed out windows of cars to me cruising the neighborhood as I was calling home thusly, want a ride. A leer and a face forcing my head a little higher in the air. On a date, I fought with somebody I thought I knew, bursting with blooming love songs, I was raped. While terror ran rampant in the tearful face, the lawful sheriff investigating questioned him first, then securing me alone to talk leered and said I ought to drop the case. Unsure of rights, I sat my head on higher, I dropped the case. Stagewise, a piano player after being refused a meal in Salt Lake City punched me to the floor after hurling hainty bitch. I worked on crutches for two weeks while a nightclub owner leered. The air was getting thinner. In Honolulu, the sound was so blatant, I became finally deaf, getting higher. By now, I knew I was a singer and sang, getting higher. In Hollywood, press agents reported of my bitchiness and in the thinness of the air, I saw you. Then somebody you said you knew screamed bitch. When I ran to you for cover, you in your fair gave me the just desserts a man gives a bitch. Locked by now into bitchness, I began to see dimly because of blooming love songs where things can lead when people labor under the bitch theory. I finally heard bitch. I am high.“

Nachdem sie im Gespräch von 1996 das Gedicht aufgesagt hat, fügt Lincoln an: „I survived my youth. Sometimes it was dangerous, but still I’m not complaining. A lot of things happened because I was pretty. Some of them were negative and some of them were positive. Mm-hmm.“

Auf die „dues“ angesprochen, das Umfeld, die Atmosphäre in den Kreisen, in denen sie damals verkehrte, sagt Lincoln: „It’s a spirit and it hangs in the corners in the dark and it loves somebody innocent to abuse. I met that spirit when I went to Honolulu. Corruption, you know. The musicians, the saxophone player said to me, ‚Anna Marie, you’re sitting on a million dollars.‘ Everybody was a prostitute and a dope addict and a dope pusher in Honolulu when I got there. My mother taught me better than that. I never did do that. They used to call me the square broad that works at the Brown Derby.“

Der beste Raum, in dem Lincoln – damals trat sie als „Anna Marie“ auf – in dieser Zeit (ca. 1952/53) in Los Angeles bespielen konnte, ist das Brown Derby (Wiki). Davor hat sie im Trade Winds (von dort gibt es eine Aufnahme von Charlie Parker mit Chet Baker) und im Lolly Chi’s gearbeitet – mit einer Ukulele und den Four Knights. Das Umfeld voller Junkies und Alkoholiker passt Lincoln nicht.

Nach einem Jahr in Honolulu kehrt sie zurück, Eddie Beal (Eugene Chadbourne auf Allmusic) wird der erste „coach“, den Lincoln je hatte. Er bringt sie 1954 in Kontakt mit dem Songwriter Bob Russell, sie lernt Benny Carter kennen. Es folgt ein Angebot, im Moulin Rouge aufzutreten (hier ein Foto, das tatsächlich von 1954 ist). Sie soll in der Show „Salse Paree“ auftreten, deren Produzent zu ihr sagt: „Well, if you do this show, if we pick you, you’ll be a star after this“ – was sie noch einige Male zu hören kriegen sollte. Sie tritt also auf und man will ihr dafür aber einen Französischen Namen verpassen – dabei ist „Anne Marie“ doch Französisch, doch gewählt wurde „Gaby“, zusammen mit ihrem englischen Familiennamen Woolridge. Manchmal wird sie auch als „Gabby Hayes“ vorgestellt, doch Bob Russell gibt ihr schliesslich den Namen „Abbey Lincoln“.

Die Arbeit mit Beal ist wichtig, weil er Lincoln austreibt, die Eigenheiten anderer Sängerinnen – „Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washigton, these people“ – zu imitieren: „‚I don’t want you to make a variation, unless you feel it,‘ and I cleaned up my — it gave me a wonderful chance to be real. Mm-hmm. I didn’t sound — I didn’t try to sound like anybody and I was practicing sincerity which is still with me. If you feel it. Eddie Beal is a great coach. He never wanted any money. It wasn’t power that he wanted.“

Lincoln arbeitet mit Bob Russell und dem Choreographen Nick Castle. Russell empfehlt ihr Designer, bei denen sie sich einkleiden könne und besorgt ihr einen Auftritt im Film „The Girl Can’t Help It“ von Frank Tashlin (Russell war mit Lionel Newman – Wiki – bekannt, dem „musical director“ des Films – siehe Korrektur von @vorgarten weiter unten). Man steckt Lincoln in ein oranges „hourglass“-Kleid, das davor von Marilyn Monroe in „Gentlemen Prefer Blondes“ getragen wurde. Der Auftritt im Film hilft in Sachen Bekanntheit (Amiri Baraka zitiert Lincoln dazu ganz anders: „No, nothing happened with that. They weren’t interested in what I was singing. They were just interested in me wearing that Marilyn Monroe dress.“ – ich glaube, das ist der Text aus dem Band „Digging“, den ich noch nicht da habe), doch sie wird schlecht behandelt:

I just sang a song and suddenly I was — they sent me to Europe and South America. I made the cover of Ebony Magazine. The girl in the Marilyn Monroe dress. I thought they were really rude to me. I got a name, but they were really impressed that a black woman had on this white woman’s dress. I knew it was disgusting. So anyway, it was about that time that I met the music. I had met Max Roach before, after I came from Honolulu, before I changed my name, when I was just singing songs at the LeMadeline in Hollywood.

1956 (oder 1957?) kommt Lincoln mit dem Filmauftritt im Gepäck nach New York, tritt in Supper Clubs auf, „wearing this dress and bouncing on the stage, so my breasts would jiggle a little“. Und es ist Max Roach, der zu ihr sagt: „You don’t have to do that.“ – „He saved me, really, from myself. He helped to save me from myself, from all this that I was involved in.“

Das Monroe-Kleid hat Lincoln, so erzählt sie der New York Times später, kurz danach verbrannt – um sicherzustellen, dass sie es nie mehr tragen würde (via L.A. Review of Books).

Doch ich greife vor …

—

1954 – die erste Single von Anne Marie:

Anna Marie with Blinky Allen and the Stardusters

„I’m A Fool To Care“ b/w „An Angel Cried“ (Flair 4545 X 1047)

Abbey Lincoln (voc), Blinky Allen (d), die anderen Musiker (g, p, b, vocal group) sind nicht bekannt.

—

Die Album-Diskographie von Abbey Lincoln

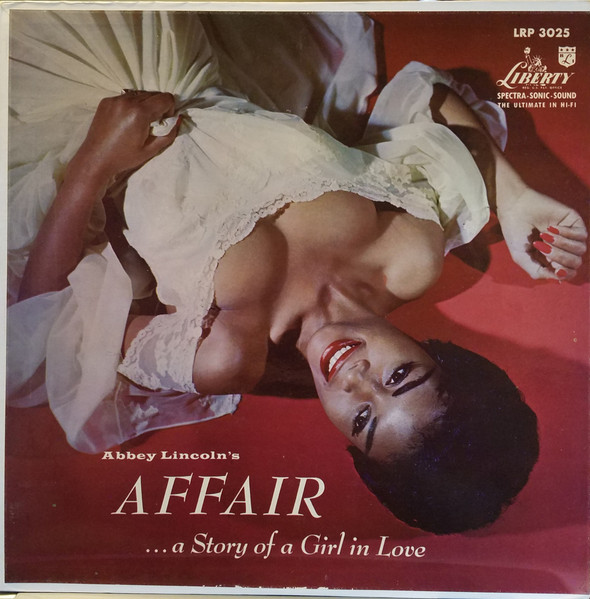

Abbey Lincoln’s Affair… A Story of a Girl in Love (Liberty, 1957)

That’s Him! (Riverside, 1957)

It’s Magic (Riverside, 1958)

Abbey Is Blue (Riverside, 1959)

Straight Ahead (Candid, 1961)

People in Me (Philips, 1973)

Live in Misty (Kiva, 1973)

Golden Lady (Inner City, 1981)

Talking to the Sun (Enja, 1984)

Abbey Sings Billie (Enja, 1989)

The World Is Falling Down (Verve, 1990)

You Gotta Pay the Band (w/Stan Getz) (Verve, 1991)

Devil’s Got Your Tongue (Verve, 1992)

Abbey Sings Billie Volume 2 (Enja, 1992)

When There Is Love with Hank Jones (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 1993)

A Turtle’s Dream (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 1995)

Who Used to Dance (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 1997)

Wholly Earth (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 1998)

Over the Years (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 2000)

It’s Me (Verve/Gitanes Jazz, 2003)

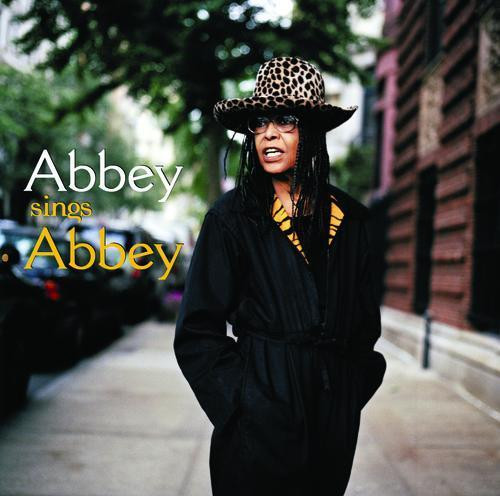

Abbey Sings Abbey (Verve/Universal, 2007)

Sophisticated Abbey: Live at the Keystone Korner (HighNote, 2015; rec. 1980)

Love Having You Around: Live at the Keystone Korner Vol. 2 (HighNote, 2016; rec. 1980)Aufnahmen mit Max Roach:

Moon Faced and Starry Eyed (Mercury, 1959)

We Insist! (Candid, 1960)

Percussion Bitter Sweet (Impulse!, 1961)

It’s Time (Impulse!, 1962)Gastauftritte und Aufnahmen mit weiteren Musikern:

Newport Rebels (Candid, 1961)

Frank Morgan: A Lovesome Thing (Antilles, 1991)

Bheki Mseleku: Timelessness (Verve, 1994)

Mal Waldron: Soul Eyes (BMG/RCA Victor, 1997)

Cedar Walton: The Maestro (Muse, 1981)

Steve Williamson: A Waltz for Grace (Verve, 1990)Bootlegs:

Sessions, Live (w/Buddy Collette, Split-LP mit Collette & Les Thompson) (Calliope, 1976)

Sounds as a Roach (w/Max Roach) (Joker, 1977)

Live/Music Is the Magic (ITM, 1994)

Love for Sale (w/Max Roach) (West Wind, 1999)—

Die Filmographie von Lincoln hat @vorgarten hier zusammengestellt:

http://forum.rollingstone.de/foren/topic/abbey-lincoln-thats-her-1930-2010/#post-11955527-

Dieses Thema wurde geändert vor 2 Jahre, 11 Monate von

gypsy-tail-wind.

gypsy-tail-wind.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaHighlights von Rolling-Stone.deNetflix: Das sind die besten Netflix-Serien aller Zeiten

Neu auf Disney+: Die Film- und Serien-Highlights im Januar

Amazon Prime Video: Die wichtigsten Neuerscheinungen im Januar

Neu auf Netflix: Die Serien-Highlights im Januar 2026

Neu auf Netflix: Die wichtigsten Filme im Januar 2026

Die 100 besten Sängerinnen und Sänger aller Zeiten

Werbungwunderbar, vielen dank!! ich lese morgen nochmal genauer, aber da sind schon einige sachen dabei, die ich nicht wusste oder kannte.

--

Das würde mich überraschen … habe ein paar einfach zu findende Artikel und v.a. das Gespräch mit Lincoln vom Oral History Project ausgeschlachtet – letzteres teils etwas umsortiert, da sie etwas in der Chronologie herumspringt.

Bob Russell gegenüber – er hat ja auch noch das erste Album vermittelt und diesbezüglich einen mässig guten Ruf – scheint Lincoln viel Respekt zu haben (drum ist auch die „Umdeutung“ – das unterstelle ich mal – durch den Marxisten Baraka etwas seltsam bis respektlos, auch wenn die Sache mit der schlechten Behandlung danach ja auch im langen Gespräch da ist … aber eben auch, dass der Filmauftritt durchaus Türen geöffnet hat, was für Baraka halt nicht sein darf

). Er hat für ein paar der schönsten Ellington-Tunes Texte geschrieben: „Do Nothin‘ Till You Hear from Me“, „Don’t Get Around Much Anymore“ und „I Didn’t Know About You“. Zudem hat er englische Texte für Lecuonas „Taboo“ und „Babalu“ verfasst, mit Carl Sigman „Crazy He Calls Me“ geschrieben … und weil ich Camarata grad bei Jeri Southern öfter antreffe auch den Camarata-Song, den ich mit Billie Holiday verbinde, „No More“, getextet. Niemand, den man allzu vorschnell abwatschen sollte, dünkt mich.

). Er hat für ein paar der schönsten Ellington-Tunes Texte geschrieben: „Do Nothin‘ Till You Hear from Me“, „Don’t Get Around Much Anymore“ und „I Didn’t Know About You“. Zudem hat er englische Texte für Lecuonas „Taboo“ und „Babalu“ verfasst, mit Carl Sigman „Crazy He Calls Me“ geschrieben … und weil ich Camarata grad bei Jeri Southern öfter antreffe auch den Camarata-Song, den ich mit Billie Holiday verbinde, „No More“, getextet. Niemand, den man allzu vorschnell abwatschen sollte, dünkt mich.--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbagypsy-tail-windDas würde mich überraschen … habe ein paar einfach zu findende Artikel und v.a. das Gespräch mit Lincoln vom Oral History Project ausgeschlachtet – letzteres teils etwas umsortiert, da sie etwas in der Chronologie herumspringt.

mal abgesehen davon, dass ich nicht wusste, wie der „elks club“ und das moulin rouge zu der zeit ausgesehen haben und ich auch nicht die bio von eddie beal recherchiert habe (danke dafür!), kannte ich die single noch nicht. beide stücke sind wirklich erstaunlich, lincoln klingt da eigentlich klarer und selbstbewusster als nach der bob-russell-zeit. interessant auch die mitsummende (weiße) vokalband the stardusters, die ja in den 40ern ziemlich stars gewesen sein müssen (und auch mal billie holiday begleitet haben).

auch barakas stück über lincoln habe ich wohl noch nie gelesen. sie ist da noch etwas offener, scheint mir, wenn es um bestimmte erfahrungen geht.

außerdem hast du lincolns familiengeschichte besser verstanden als ich, glaube ich (die mütterliche vs. väterliche linie, der unterschied von urgroß- zu großeltern etc.). beim großvater väterlicherseits (der nicht nur wegen mordes im knast war, sondern von lincoln auch mit sexuellem missbrauch in zusammenhang gebracht wird) beginnt ja offenbar die erfahrungskonstante der übergriffigen männer, über die sie ja kein blatt vor den mund nimmt – die vergewaltigung beim date, die permanente gefahr für eine junge gutaussehende frau in dem business.

einzige korrektur: THE GIRL CAN’T HELP IT (1956) ist von frank tashlin, und das ist insofern wichtig, weil es die einfache lesart (ein film mit frauen, die ihre großen oder aufgepolsterten brüste in monroe-kleidern präsentieren und danach stars sind oder auch nicht) nicht zulässt oder zumindest verkompliziert. tashlin kam ja von der cartoon-produktion und war später gag-schreiber für die marx brothers, seine perspektive auf popkultur in dem film ist einerseits voller grafischer übertreibungen, andererseits auch von einer punk-haltung und einem unorthodoxen schönheitssinn geprägt. john waters hat das aus queerer perspektive (aber eigentlich aus der perspektive des 10-jährigen jungen, der sich damals in den film verliebt hatte) hier alles sehr unterhaltsam aufgedröselt:

eigentlich erzählt der film ja die geschichte eines abgehalfterten star-agenten, der julie london zum durchbruch verhalf (also bobby troupe, der ja die musik zu THE GIRL… schrieb) und nun die untalentierte geliebte eines mafia-bosses in 6 wochen zum star machen soll. jayne mansfield ist dann die cartoon-übertreibung einer einfältigen blondine, wobei sie im schauspiel deutlich macht, dass sie das weiß (waters sagt: eine dragqueen von innen). die musikwelt, durch die der agent sie führt, befindet sich im umbruch, weswegen ja auch die beatles und ganz andere leute fan dieses films waren: es tauchen frühen rock-n‘-roll-acts auf, little richard (der tatsächlich erfahrungen als dragqueen hatte), eddie cochrane, gene vincent, die schrecken der weißen eltern und idole der sich emanzipierenden weißen jugend, hier aber nicht in schäbigen clubs, sondern in unfassbarem hollywood-look, vor glitzervorhängen, in violettem licht. sie sind die ablösungen von julie london, abbey lincoln und anderen hochklassigen supper-club- und revue-acts. london taucht im film sogar als geist auf (unglaubliche szene):

und was auch immer man über dieses kleid sagen will – die szene mit dem lincoln-auftritt ist unfassbar toll. der schwenk von der schattensilhouette auf den körper, der rot-blau-kontrast, der ganz leicht glitzernde vorhang, lincolns schon deklamatorischer vortrag, wie die kamera mit ihren bewegungen mitfließt… das ist unglaublich filmisch:

gypsy-tail-windBob Russell gegenüber – er hat ja auch noch das erste Album vermittelt und diesbezüglich einen mässig guten Ruf – scheint Lincoln viel Respekt zu haben (drum ist auch die „Umdeutung“ – das unterstelle ich mal – durch den Marxisten Baraka etwas seltsam bis respektlos, auch wenn die Sache mit der schlechten Behandlung danach ja auch im langen Gespräch da ist … aber eben auch, dass der Filmauftritt durchaus Türen geöffnet hat, was für Baraka halt nicht sein darf

). Er hat für ein paar der schönsten Ellington-Tunes Texte geschrieben: „Do Nothin‘ Till You Hear from Me“, „Don’t Get Around Much Anymore“ und „I Didn’t Know About You“. Zudem hat er englische Texte für Lecuonas „Taboo“ und „Babalu“ verfasst, mit Carl Sigmn „Crazy He Calls Me“ geschrieben … und weil ich Camarata grad bei Jeri Southern öfter antreffe auch den Camarata-Song, den ich mit Billie Holiday verbinde, „No More“, getextet. Niemand, den man allzu vorschnell abwatschen sollte, dünkt mich.

). Er hat für ein paar der schönsten Ellington-Tunes Texte geschrieben: „Do Nothin‘ Till You Hear from Me“, „Don’t Get Around Much Anymore“ und „I Didn’t Know About You“. Zudem hat er englische Texte für Lecuonas „Taboo“ und „Babalu“ verfasst, mit Carl Sigmn „Crazy He Calls Me“ geschrieben … und weil ich Camarata grad bei Jeri Southern öfter antreffe auch den Camarata-Song, den ich mit Billie Holiday verbinde, „No More“, getextet. Niemand, den man allzu vorschnell abwatschen sollte, dünkt mich.

ja, russell ist eine interessante figur, nicht nur, weil er für ihren künstlerinnen-namen verantwortlich ist. lincoln deutet ja an, dass sie zusammen viel über ihre außenseiter-erfahrungen gesprochen haben, wie jüdisch- und schwarzsein sich in dem business manifestiert und worin das vergleichbar ist. bei dem thema haben ansonsten viele schwarze künstler:innen ja nicht weiter geschaut als auf ungleich verteilte geld- und machtpositionen, und da gab es natürlich auch zwischen russell und lincoln entscheidende differenzen („i owe her“). fand ich interessant, dass solche themen außerhalb der eigenen community diskutiert wurden.

--

Tausend Dank für die tollen Ergänzungen! Ich bin wahnsinnig schlecht dabei, über Musik zu schreiben und dabei auch noch andere Medien zu berücksichtigen (was hier so an YT-Links geteilt wird, krieg ich allerhöchstens zu 10% mit – passt einfach nicht in meine Routinen). Das Gespräch mit Waters habe ich gerade angeschaut (und den entsprechenden Absatz oben korrigiert – da hatte ich gestern nicht genau hingeguckt, pardon und merci!) – das ist echt super. Und die Inszenierung von Lincoln mit Farbe, Silhouette, Licht/Schatten ist echt der Hammer! Den Schlüsselsatz sagt Waters vielleicht über Jayne Mansfield: „How can you be pitiful if you in on a joke?“ – den Film kenne ich nicht und hab jetzt auch die Ausschnitte angeschaut. Grossartig in der Tag, der London-Auftritt als Geist! (Ordentlich Arbeit fürs wardrobe department

– und da ist ja auch total die Sirk-Ästhetik!)

– und da ist ja auch total die Sirk-Ästhetik!)Finde ich jetzt echt interessant, den Punkt, auch mit Deinem Kommentar dazu, dass Lincoln vielleicht gegenüber Baraka offener war (kann ich mir irgendwie schwer vorstellen, aber das ist nur ein Gefühl, klar). Meine Lesart bleibt – wie oben angetönt – dass Baraka dem Ganzen einen „spin“ gibt, der gut in sein Narrativ passt. Und das Gespräch mit Waters könnte immerhin insofern dafür sprechen, als dass Lincoln vermutlich auch damals schon klug genug war um „in on it“ zu sein und die ganze Inszenierung eben auch zu durchschauen? (Natürlich ist das, was sie danach als schlechte Behandlung erlebt davon nicht tangiert, bzw. die kann ja wiederum darauf abfärben, wie sie das alles im Rückblick liest?)

Die Sache mit dem Missbrauch, dass es in der Familie Lincoln – also bei ihren Eltern, unter ihren Geschwistern – keinen Inzest gab usw. habe ich tatsächlich gestern einfach mal ausgeblendet, da fehlte mir noch der weitere Kontext dazu (ich habe das Gespräch noch nicht zu Ende gelesen).

PS: Bei Eddie Beal hilft es, älteren Jazz ein wenig zu kennen … ich kenne den Namen von einigen Aufnahmen und war drum neugierig genug, weiterzugucken. Und Chadbournes Biographien bei Allmusic sind ja eh super!

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaich glaube, ich kannte THE GIRL… (auf deutsch hieß der „schlagerpiraten“!) schon, bevor ich mich mit jazz oder gar mit abbey lincoln beschäftigt habe, er lief relativ häufig im fernsehen. nach der lesart von waters weiß ich ein bisschen besser, was mich wohl damals so begeistert hat

was baraka angeht, denke ich, dass er schon ein bisschen betonung auf ihre ‚entlastungen‘ des afroamerikanischen mannes und seiner rollenkonflikte legt (mit ihrer afrikanischen mehrehen-these meint lincoln ja nie sich und die frauen…), aber sie provoziert auch: die ellington-geschichte hat sie woanders nicht erzählt, glaube ich. auch, wie sie von den schwarzen jazzmusikern zunächst angefeindet wurde. dass ebony sie mochte, bevor sie „social“ wurde – das ist echt ein interessantes thema, welche rolle die schwarzen magazine im kampf um bürgerrechte gespielt haben – hier natürlich an den klügeren schwarzen publizisten gerichtet. (das meinte ich: hier merkt man, dass sich zwei schwarze menschen über das gemeinsam, aber aus verschiedenen perspektiven, erlebte feld unterhalten.)

aber es ist doch krass: da wird der vater hervorgehoben, der zwei häuser für die familie gebaut hat, aber nicht die mutter, die

1712 kinder (neben denen, die sie verloren hat) allein großgezogen hat. (und was sie bei plaxton erzählt: die weißen familien, die mutter lincoln hasen geschenkt haben, damit die familie nicht verhungert.)--

Das mit den Hasen ist etwas vom Krassesten in dem Gespräch, ja! Dazu gehört (Baraka) wohl das hier:

Calvin’s Center was one of the stops on the Underground Railroad. A lot of those folks there were light-skinned with straight hair. The runaway slaves married the whites and Indians there. So they didn’t socialize with us much.

Hatte gedacht 17 Kinder sei inkl. die fünf, die nicht überlebt haben (es gab 12, Lincoln war Nr. 10, für Nr. 12 hat der Vater gesungen).

Und danke für die Erläuterung zum „gemeinsam … unterhalten“, das war mir wirklich nicht ganz klar.

Zu den Einflüssen und den Erlebnissen in der Zeit in Honolulu und L.A. gibt es bei Baraka ein paar zitierenswerte Absätze – Ellington, Holiday, Washington, Armstrong usw. (und die Schreibweise „Paitch“, die ich im folgenden Post – der nebenher in Arbeit ist, schwierig

– bemängle, ist tatsächlich auch aus dem Text von Baraka):

– bemängle, ist tatsächlich auch aus dem Text von Baraka):Talking about how and what she learned and from whom: “I really didn’t know much about the music then. But I began to meet people. I met Duke [Ellington] coming from Hawaii. He used to stay in a suite in one of the two black hotels in L.A., the Watkins. That’s when it was all segregated. So when Duke was in town, he always stayed at the Watkins.

“So I decided I wanted to sing with Duke. He hadn’t asked for a singer. But I just went up to see him, and hit on him, telling him I wanted to sing with the band. Duke didn’t say much, he just began to undress and walk toward the bedroom. Then he rolled the bed down, and I walked out of there.” Abbey is having much fun running this down. “I never told that to any writers before. I guess he was letting me know, up front, so I got right out of there.

“I met a lot of people in L.A. and Honolulu. I met Billie Holiday, Cozy Cole, Louis Armstrong. I never got close to Billie. Actually, I was afraid of her. I mean I respected her so much. I wasn’t going to walk up to her like some of these singers do to me and start talking about myself, give me their latest record.” So it is that Abbey describes her relationship with Billie as “kind of standoffish.”

“Louis was a wonderful man. He didn’t look at a woman’s behind, he looked right into your eyes and he was a great friend. Dinah Washington and Sassy liked me. Actually, they treated me as a mascot, ’cause I was still learning the music. I already had a career, as a glamour queen. I didn’t have to be there”-she means not only Honolulu or L.A.-“but I had to be there. I had to be in the music.”

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbagypsy-tail-windHatte gedacht 17 Kinder sei inkl. die fünf, die nicht überlebt haben (es gab 12, Lincoln war Nr. 10, für Nr. 12 hat der Vater gesungen).

ja, sorry, da hatte ich den überblick verloren.

--

soulpope "Ever Since The World Ended, I Don`t Get Out As Much"Registriert seit: 02.12.2013

Beiträge: 56,976

Beeindruckende Detektivarbeit …. muss das erst in Ruhe schmökern …. nachhaltigen Dank bereits jetzt ….

--

"Kunst ist schön, macht aber viel Arbeit" (K. Valentin)ihre filmografie könnte man vielleicht noch einbauen, davon kenne ich noch wenig:

THE GIRL CAN’T HELP IT (frank tashlin, 1956, gastauftritt)

NOTHING BUT A MAN (michael roemer, 1964, hauptrolle, new cinema award: best actress, biennale di venezia)

FOR LOVE OF IVY (daniel mann, 1968, nebenrolle, golden-globe nominierung: best supporting actress)

THE NAME OF THE GAME (tv-serie 1968-71, folge „the black answer“, 1968, regie: leslie stevens, nebenrolle)

MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE (tv-serie 1966-73, folge „cat’s paw“, 1971, regie: virgil w. vogel, nebenrolle)

ON BEING BLACK (tv-serie, 1 folge, 1971, hauptrolle)

SHORT WALK TO DAYLIGHT (tv-film, barry shear, 1972, ensemble-hauptrolle)

MARCUS WELBY M.D. (tv-serie 1969-76, folge „angela’s nightmare“, 1974, regie: leo penn, nebenrolle)

ALL IN THE FAMILY (tv-serie, 1971-79, folge „what’ll we do with stephanie?“, 1978, regie: paul bogart, nebenrolle)

MO‘ BETTER BLUES (spike lee, 1990, nebenrolle)interessant vielleicht noch, dass der titelsong des films FOR LOVE OF IVY, von quincy jones geschrieben und für den oscar nominiert, damals von shirley horn gesungen wurde:

und für die titelsequenz von DRUGSTORE COWBOY (gus van sant 1989) hat lincoln wiederum (begleitet von geri allen) „for all we know“ (coots/lewis) eingesungen:

--

Im selben Jahr, in dem Lincolns Aufritt für „The Girl’s in Love“ (s.o.) aufgezeichnet wird, nimmt sie auch ihr erstes Album auf. Doch ein paar Monaten davor, im Juli 1956, entstehen sechs Stücke, die vielleicht fast von grösserem Interesse sind. Nur zwei von ihnen kommen damals als Single heraus, auf zwei weiteren wird sie nur von Gitarre, Vibraphon und Kontrabass begleitet: „Warm Valley“ (Ellingtons Vulva-Song mit Lyrics von Bob Russell) und „You Do Something to Me“ von Cole Porter. Lincoln klingt in „Warm Valley“ für meine Ohren etwas verhalten, auf jeden Fall zurückhaltender als mit ihrem deklamatorischen Cabaret-Stil im Film. Im Porter-Song klingt ihre Stimme offener – aber der ist praktisch vorbei, kaum hat er angefangen.

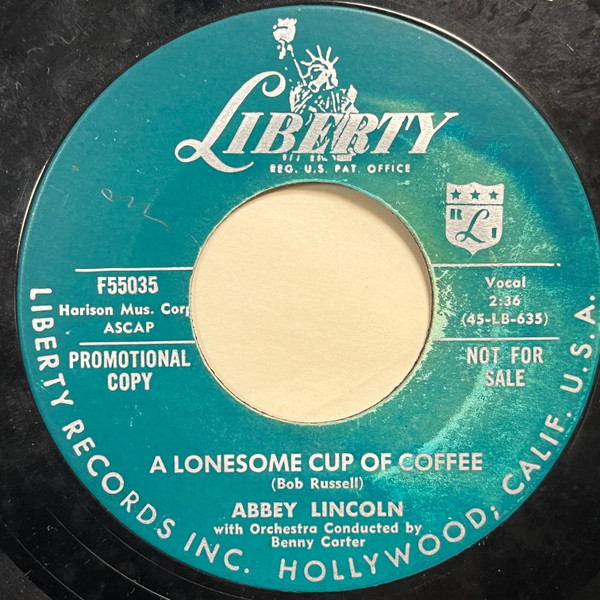

Noch bei zwei weitere der sechs Stücke hatte Russell seine Finger im Spiel – und klar gibt es da ein Machtgefälle. Ich denke, diese Problematik konnte im Musikbusiness (vom Film schweigen wir besser mal, oder?) bis heute nur sehr selten halbwegs gelöst werden. Gelöst ist da ja nur, wenn auch die Umstände der Produktion und die Vertriebskanäle anders organisiert werden können. Und es ist ein Thema, das auch hier im Forum schon zu Friktionen geführt hat (weniger in der Jazzecke glaub ich), weil auch die Mehrzahl der Fans lieber nichts davon wissen mag, was allers hinter den Kulissen passiert. Lincoln ging damit aber später sehr offen um. Sie singt Ellingtons „Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me“ mit Russells Lyrics, „The Answer Is No“ von Harold Levey, und dann – auf dem CD-Reissue des Debutalbums von 1993 an den Schluss gestellt – die zwei auf einer Single veröffentlichten „Lonesome Cup of Coffee“ (hier hat Russell gleich Text und Musik geschrieben) und „She Didn’t Say Yes“ (als „I Didn’t…“) von Jerome Kern/Otto Harbach.

Benny Carter hat die vier Stücke arrangiert, durchaus attraktiv und abwechslungsreich, wenn man die vier zusammen nimmt. In Russells Song gibt es eine Altflöte, gedämpftes Blech (leise Ellington-Anklänge – wobei bei Carter solche Vergleiche eh ins Leere gehen: das ist fucking Benny Carter!), ein tingelndes Klavier, einen rollenden Bass, ein paar Rim-Shots – und eine ziemlich toll aufgelegte Lincoln:

Am 5. und 6. November 1956 entstand dann das Debutalbum, auch wieder für Liberty Records. Produziert hat Russell Keith, aber die Fäden gezogen hat Bob Russell, von dem ein Song („Affair“) komplett stammt, während er zu vier weiteren (es gibt 12, das ist Konfektionsware) die Texte schrieb (Ellington, Camarata, Sigman, Harold Spina). Daneben gibt es Gershwin, Rodgers/Hart usw.

Aus dem Gespräch mit Sally Plaxson von 1996:

I was learning. The first album I made with Max — well, my first album was with Benny Carter, Jack Montrose, and Marty Page, standards, that some of them — most of them Bob Russell had written. He was helping me and I was helping him.

[…]

The name of the album was „Affair: Story of a Girl in Love,“ and they photographed me upside down with my breasts spilling out in this negligee, this yellow negligee, on a label called Liberty Records. Bob thought that they were going to laugh when they saw a picture of Abbey Lincoln superimposed over Abraham Lincoln looking like a tart, but nobody got it. It wasn’t funny to them. I heard one woman at the bank laugh. „Abbey Lincoln.“ That’s the only reaction. They used a picture of a penny and superimposed my image over it in Marilyn Monroe’s dress. Nobody got it, and wrote this song for me to sing in „The Girl Can’t Help It,“ „Spread The Word, Spread the Gospel, Speak the Truth, It Will be Heard Wearing this Dress.“ It was really contradictory, you know. It could have taken me out, too. I got passed that.

Ich verstehe leider die Beschreibung des Covers („they used a picture of a penny and superimposed …“) überhaupt nicht.

Auf die Frage, ob sie sich damals bewusst gewesen sei, wie diese Bilder von ihr wirkten, verneint sie (was gegen meine obige These zu Baraka usw. spricht):

No. It was my first time. How would I have known? I hadn’t wished to be a star. I can honestly say that. I always dreamed of a man. I didn’t dream of children, but I was going to meet this god who was going to save me from myself. I didn’t dream of being a star or being a movie star or any kind of other star. I still don’t care anything about it. But I think it just was my lot because I’ve had plenty of chances to be a super star. They can give it to their mother. I don’t want everybody to know my name.

Bob Russell wählte die Musiker und steuerte einiges an Material bei – doch Lincoln sagt im Gespräch von 1996, dass sie grundsätzlich die Songs ausgewählt und auch die Story des Albums, die „Affair“, entwickelt habe: „the love story of a girl, a love song, a love story that goes bad because all I ever knew was about a love affair that went bad, and so because I’ve always picked the songs I would sing, people don’t pick my material. They may pick the musicians, help me pick the musicians, but I pick the songs.“

Dieser Kontext ist heute Gold wert, denn Russells Liner Notes wären ohne ihn inzwischen zumindest teilweise recht schwierig (und sie bleiben es im patronisierenden Tonfall auch mit dem Kontext noch). Doch er äussert sich auch zu seinem Verständnis von Songs – und davon verstand er ja tatsächlich etwas. Ich tippe die Liner Notes rasch ab, sie sind kurz und füllen nochmal einige Details aus der Zeit (1954-56) ein, die in den anderen mir vorliegenden Texten fehlen. Und alles in allem ist das doch ein schöner Text, der viel Wertschätzung ausdrückt. Natürlich enthält der Text auch einiges an Promo-Sprech – aber er liegt in vielem ja auch goldrichtig, zumindest wenn man es nicht auf „Affair“ sondern auf das, was danach folgen sollte, bezieht.

AFFAIR … The story of a girl in love … told by Abbey Lincoln … in song. Songs, good songs, have something to say. They hava a beginning, a middle and an end, as in life, and are a facet of life itself. Any real-life situation involving people is a series of scenes as in a play – so our album which uses the dramatic technique of the song to forward and develop the action and tell the story of a woman looking for love. This story-telling with songs for scenes may very well be an innovation in album planning.

Let this album, then, be your calling card to the poignant memory of a new romance, its bright hope of „this time – now,“ its sad clinging to what might have been, its almost … its … its

As the cover of this album would indicate, Abbey Lincoln has been blessed with the lines, curves, arcs and semi-circles in the tradition of classic beauty. Anything said would be superfluous. One photograph bespeaks a thousand words.

However, Abbey possesses qualities her picture can only suggest. If she could reach out and touch you as she almost does with her smile, or warm you as she can with the glow and sometimes fire in her eyes, you, too, might get caught up in the web.

There is a vitality about her a vibrancy a directness; an intelligence – all of which is reflected in the type of song she sings and the way she handles the lyrics, which lets you know she has been there once or twice before. She also knows you’ve been there once or twice yourself.

Chicago-born, Kalamazoo-bred, jazz band trained and honky-tonk educated, Abbey landed in Los Angeles in October 1954 after a year-and-a-half singing stint in Honolulu. Then for the next year, she was the production singer at the lavish Moulin Rouge.

In September 1955 Abbey struck out on her own. „Struck out“ in this case is an apt phrase. The following ten months were disheartening. It was one step forward and two steps back. Then, suddenly, the background, the years of experience, the opportunity all began to mesh. After an audition, she was booked in June 1956 for two smash weeks at the world-famous Ciro’s in Hollywood and was signed exclusively by Liberty Records who released her first record „Lonesome Cup of Coffee“ and „I Didn’t Say Yes“ to synchronize with her even more successful return engagement at Ciro’s in September 1956.

During this time she appeared on several coast-to-coast TV programs, became Oscar Levant’s vis-a-vis on his tremendously popular local TV show and guest starred in Twentieth Century Fox’s „The Girl Can’t Help It.“ This was followed by three weeks of „standing room only“ at Beverly Hills‘ new Ye Little Club and then to the Copacabana in Rio De Janeiro, followed by one month at Chicago’s Black Orchid.

Abbey get around but that’s because she’s on her way. If she happens to pass your way – stop, look and listen. You’ll be entranced.

~ Bob Russell

Detail, weil ich selber grad etwas ungläubig war: ja, Rio de Janeiro in Brasilien – das erwähnt Lincoln im Gespräch 1996 auch schon, ich habe den betreffenden Absatz im ersten Post zitiert: „I got a lot of mileage out of that film. I just sang a song and suddenly I was — they sent me to Europe and South America.“

Was die Musik angeht sind das keine besonders bemerkenswerten Aufnahmen. Aber sie sind auch weit entfernt davon, schlecht oder schwach zu sein Es fehlt ihnen aber das besondere Etwas. Marty Paich (nicht „Page“ oder „Paitch“, wie er im Text von Baraka heisst) hat sechs Stücke mit Streichern arrangiert, Jack Montrose und Benny Carter je drei mit einigen Holdbläsern einer Trompete (die klingt manchmal – z.B. in „This Can’t Be Love“ – sehr charakteristisch, denke eigentlich, dass gewisse Herren Kritiker die erkennen könnten, wenn sie sich nicht zu schade wären, sich in die Gefilde des Vocal Jazz hinab zu begeben?).

Lincolns Stimme ist zwar erkennbar, aber wie auf den sechs Stücken vom Juli klingt sie weniger stark als auf der frühen Single von 1954 oder im Film, als würde sie sich in der Diktion und auch bei der Gestaltung etwas zurückhalten (früher, also bevor ich mit ihrer Stimme klargekommen bin, hätte ich das übrigens gerade begrüsst, aber das war kein Werturteil sondern bloss eine Frage der persönlichen Vorlieben, dessen was gefällt, und was halt nicht). Ein kleines Highlight ist für mich Montroses Rumba (oder was das halt ist) über „Would I Love You“ (Russell-Spina):

In Paichs „Crazy He Calls Me“ (da kommt in den Passagen im Dialog mit der gedämpften Trompete dieser typische Lincoln’sche Finish, der Glanz in der Stimme, wieder zum Vorschein) kommen einzelne Xylophon-Töne zum Einsatz. Es gibt in diesen Arrangements durchaus Liebe zum Detail und einiges an Nuancen. Aber Lincoln sollte sich ganz anders entwickeln und das Album ist daher nicht zu früh oder einfach zum falschen Zeitpunkt entstanden, sondern sie ist quasi miscast hier. Für wen anderes hätten das echt gute Backings sein können. Im abschliessenden „No More“ (Camarata-Russell) wird die Nähe zu Holiday da und dort hörbar – aber grad die Abschlüsse der Songzeilen gestaltet Lincoln schon in ihrer ganz eigenen Art. Abgesehen vom harten Edit ein paar Sekunden vor Schluss (ev. hat man da einfach aus Versehen das Gesangsmikrophon zu früh ausgeknipst und es gar kein Edit?) ist das eine der stärksten Performances auf dem Album:

Billie Holiday (Decca, 1946):

Eine kleine Fussnote zum Thema Machtgefälle: Auf der Rückseite des CD-Reissues stehen nur die Namen von Carter und Paich. Auf der Rückseite des Booklets ist Jack Montrose dann auch zu finden und es steht sogar, wer welche Stücke arrangiert hat. Aber als Verkaufsargument war Montrose damals halt längst nichts mehr Wert, also streichen. Am Platz kann es nicht gelegen haben.

—

Und in diesen Kontext passt wohl auch noch die Geschichte, die Lincoln 1996 über Las Vegas erzählt:

I only worked Las Vegas a couple of times, thank God. […] Hated it. Las Vegas is a place where people go who don’t see themselves as creative. If you’re creative, you’re like in the manger. At Blues Alley, in the alley. Las Vegas is for show business. I went to Las Vegas, to Caesars Palace once and I went there with John Coletrain’s Africa. I had written a lyric to it, and I was singing „Naturally, Live for Life.“ They fired me, but Oscar Brown told me that they had fired him the same way. So, I wasn’t surprised. They fired me in the lobby and American Gilda Variety Artist let them take $6,000 of my money. It was after I had made „For Love of Ivy.“

I didn’t ask them for the job, but I could have said to them I’m not coming in. I was trying to be cooperative, you know, did my best. I wore some very beautiful garments. I was on a bill with Reagan’s daughter, Mickey Rooney’s son, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Hilton’s daughter. They had all these names on the marquee. Hilton, Reagan, Rooney, and my name Lincoln. So, I was — and they had me close the show, right? They had already opened it. It was a disaster. It had been there for about a week and the conductor told Roach, „She can’t save the show.“

So, I would come on the stage and I would say to them, „Well, it’s interesting that Caesar’s Palace is featuring the children of famous people this week. It’s a very well-kept secret, but as a matter of fact, I am the great-great-great illegitimate daughter of Abraham Lincoln,“ and they would laugh, but I didn’t have anything to follow it with.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaUnd separat nochmal eine längere Passage aus dem Gespräch von 1996, in dem Lincoln sich über ihre Vorbilder und besonders über Billie Holiday äussert – und auch einen Vergleich zieht, wie junge Sänger*innen sich damals und in der Gegenwart der 90er (und sicherlich auch heute noch) gegenüber ihren Vorbildern verhalten:

ABBEY LINCOLN: […] Louis Armstrong was a singer. Most musicians are afraid to sing. It’s somehow a step down or something, and a lot of the singers today are imitating the horns. They’re jealous of the saxophones, saxophonists, but the saxophone is made. It has a range like the piano has a range. So, what is all this scatting? Ella used to scat after she told the story, after she sang the song exactly as the composer wrote it and the lyricist. Then she would improvise.

The singers, many of them today start out improvising because they think they’re singing jazz. There is no such thing as jazz. There’s only a song and your spirit and your ancestors. I don’t know what I’d have done without Billie Holliday or Bessie Smith or Sarah, all these. I follow in a tradition. Women who never sounded like anybody but themselves.

But then smoking was allowed in public places and you didn’t have to fasten your seatbelt. The government wasn’t responsible for your life in the car. Even though you owned the car, you can’t disconnect the airbags, unless the government says you can. It’s another time and the music reflects it, and this is dangerous.

SALLY PLAXSON: What did those women do? What did they leave that made it possible for you to take your place in that lineage?

ABBEY LINCOLN: Just their footprints. That’s all. They were all original and they had a philosophy of life that didn’t encourage anybody to approach them in any kind of a phony manner. They knew how to be real and I was afraid to go up to any of these queens and say, oh, Sarah, I wish you’d listen to my album or I wish you’d — do you think I could take a few lessons from you. I mean, I wouldn’t have dared. I wouldn’t have dared. Billie Holliday, you listened to the recording. What do you mean, teach you? Who are you, darling? Things have changed. Mm-hmm.

SALLY PLAXSON: Did you ever meet her, talk with her?

ABBEY LINCOLN: Billie? I met her. I never talked with her because I didn’t feel like her peer. I didn’t know how to have a conversation with Billie Holliday. I was in her presence a couple of times. She came to see me when I was in Honolulu at the Tradewinds. She came a couple of times. I think she was getting away from the atmosphere of where she was. It was only a few blocks away and she brought her little dogs, Mexican Chihuahuas, sat at the bar and drank whiskey out of a glass, and for a little while, I thought it was the whiskey that made her what she was, but I figured that out. It didn’t take me long.

She was a great queen without her court, and she would stand on the stage and hardly anything would ever move. Her eyes would slide from side to side and nobody talked. The room was still like that. Nobody talked. That was the only time I ever had seen her perform, but she did come where I was twice, but I didn’t go to the bar and say, oh, hi, Billie.

The singers approached me like that, like they really, you know, are my equals now, yes, and I’m friendly, but I wonder about it.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbavorgarten

und für die titelsequenz von DRUGSTORE COWBOY (gus van sant 1989) hat lincoln wiederum (begleitet von geri allen) „for all we know“ (coots/lewis) eingesungen:

Sehr, sehr schön, danke!

Ca. 1989 sagt die Diskographie von Mike Fitzgerald – kannte ich nicht, wie ich von den Filmen eh ausser „Mo‘ Better Blues“ bisher keinen kenne. Musste das Jahr nachgucken, weil diese Aufnahme einen Touch von Spät- wenn nicht gar Letztwerk hat, eine vollkommen eigene Intonation vor allem, die in sich aber die meiste Zeit völlig stimmig ist.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169 – 13.01.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbavielen dank einmal mehr, ich freue mich schon darauf, das debüt mit diesen kommentaren nochmal zu hören!

der song für den DRUGSTORE COWBOY, das billie-holiday-programm und der autritt in MO‘ BETTER BLUES kamen alle kurz vor dem von allard ermöglichten comeback, irgendwie lag das alles schon in der luft.

die promo-bilder… hab noch sowas hier gefunden:

anna marie und gaby lee zwischen honolulu und hollywood…

das ciro’s in los angeles (sunset boulevard) war allerdings einer der glamourösesten nightclubs der 50er, wie es aussieht. da könnte marilyn monroe abbey lincoln live gesehen haben, in welchem kleid auch immer.

--

gypsy-tail-windEin kleines Highlight ist für mich Montroses Rumba (oder was das halt ist) über „Would I Love You“ (Russell-Spina)

ich würde sagen, das ist ein tango, oder?

hab das album und die 6 bonustracks gerade auch nochmal gehört und bin ganz bei dir. eigentlich kann ich kaum was damit anfangen, ich höre die schönen arrangement-details, ich höre auch lincolns bühnenerfahrung und mag den programm-musik-aspekt der tragischen entwicklung einer liebesbeziehung, aber das vibrato, das, wenn sie es besonders dramatisch leise einsetzt, etwas leicht irres bekommt, ist einfach nicht schön. es bildet einen widerspruch zum zusammenkleben, das es behauptet, es steigt vom sound her aus, kratzt und reibt am setting. für mich bleiben die probleme ja eigentlich bis STRAIGHT AHEAD, das ist allerdings ein quantensprung (und auf dem weg gib es schon viele tolle momente).

aber wenn man sich lincoln mit diesem russell-programm im ciro’s vorstellt, muss das ja schon funktioniert haben, wenn leute da schon max roach bescheid sagen, sich das mal anzusehen… „no more“ mit dem offenen holiday-bezug ist, wie du sagst, schon ein hinweis auf kommende attraktionen. vielleicht wäre eins dieser intimen settings nur mit gitarre oder so besser für das debüt gewesen, da hätte sie etwas dramatischer mit den rhythmischen vorgaben umgehen können (wie im intro von „take me in your arms“). aber das storytelling, das hier versucht wird, scheint mir eher geeignet für eine dame in ihren 40ern, die schon etwas mehr erlebt hat.

--

-

Dieses Thema wurde geändert vor 2 Jahre, 11 Monate von

-

Schlagwörter: Abbey Lincoln, Jazzsänger*innen, Max Roach, Modern Jazz, Vocal Jazz

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.