Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Tenor Giants – Das Tenorsaxophon im Jazz › Re: Tenor Giants – Das Tenorsaxophon im Jazz

(Wardell Gray – Photo von Francis Wollf)

A kid . . . who stood slumped with his horn and blew like Wardell . . . and we all stumbled out into raggedy American realities from the dream of jazz. —Jack Kerouac, Visions of Cody

Die bizzarre Story zum tragischen Ende des wunderbaren Wardell Gray

Song of the Thin Man

Wardell Gray’s Princely LamentBy Stuart Mitchner Tuesday, Jun 3 2003

Wardell Gray, Stan Hasselgaard (photo: courtesy Richard Carter)A kid . . . who stood slumped with his horn and blew like Wardell . . . and we all stumbled out into raggedy American realities from the dream of jazz. —Jack Kerouac, Visions of Cody

The author of a 1954 Melody Maker piece, „Return of the Thin Man,“ compared interviewing tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray to „attending a literary tea . . . with copious comments on chess, Shakespeare, James Jones, Norman Mailer and other Gray favorites.“ Since Gray also read Sartre and Camus and was involved in leftist politics and the NAACP to the extent that the FBI had a file on him, he would have found much to interest him in Norman Mailer’s 1957 essay „The White Negro.“ As a black jazz musician nourished intellectually and creatively by a predominantly white culture, he might even have taken the title personally. In Mailer’s depiction of the white hipster, it’s the other way around, of course: „The source of Hip is the Negro“ who „must live with danger from his first day.“

Wardell Gray could never have read „The White Negro“ because the dangers he lived with killed him at 34, less than a year after the Melody Maker interview. If the manner of his death—an unsolved mystery involving narcotics and abandonment in the desert—was a grim illustration of Mailer’s dynamic, the character of his life suggests something else. While it’s true that he lived and died in Mailer’s „Wild West of American night life,“ he managed to play chess, read broadly, become a culinary virtuoso, and enthuse about a wide variety of subjects including classical music and other arts. According to Hampton Hawes in his autobiography Raise Up off Me, „When white fans in the clubs came up to speak with us, Wardell would do the talking while the rest of us clammed up and looked funny.“

In Abraham Ravett’s 1994 documentary, Forgotten Tenor, a white friend who knew him in Michigan when she was in her teens suggests that he was „ahead of his time as far as knowing who he was as a person and he wasn’t about to back off or be treated unfairly.“ She saw that he „would have a problem because he didn’t have that better-know-your-place attitude.“

One place Wardell Gray knew he belonged was the jazz hierarchy. Sought after and admired by Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Earl Hines, Benny Carter, and Charlie Parker, among others, he was praised in Jazz on Record for his „unparalleled ability to create long swinging solos devoid of the tautology which mars so much of the work of LP-era musicians.“ When asked by Leonard Feather who the best player of the post-war generation was, Lester Young „gave a blanket endorsement of Wardell Gray.“ Having been quoted more than once on his distaste for bop, Benny Goodman heard the Thin Man firsthand at a California concert and admitted to a Metronome interviewer, „If Wardell Gray plays bop, it’s great. Because he’s wonderful.“ Within months, Goodman formed a new septet featuring Gray. Even after being chosen by the King of Swing, Gray’s sense of „who he was“ was so strong that when people were congratulating him for being with Goodman, he told his wife he wished somebody would talk about how Goodman was playing with him.

Still, he lived with the day-to-day knowledge that no matter how accomplished a musician he became, no matter how much he read, thought, or hoped, he would never escape the prison defined by prejudice. Nor would he escape heroin after spending most of his life resisting it and counseling against it. Prejudice was the place he lived in and died on May 25, 1955, his body found in a drainage ditch in the desert near Las Vegas with a broken neck and head injuries. If he’d been white, the police would have conducted a thorough investigation. As it was, they were in a hurry to close the case, leaving questions that inspired Bill Moody’s 1997 detective novel, The Death of a Tenor Man.

Seven years before his death Gray was onstage at the Flamingo in Jim Crow Las Vegas playing with Goodman’s big band. Thanks in great part to his exposure with Goodman, he had jumped from 27th to fourth in the tenor sax division of the 1948 Metronome poll. He was the only African American in the band, and its star soloist and bandmaster, expected to lead in the leader’s absence. He was not expected to eat in the dining room, however, nor permitted to enter through the main entrance, and he had to room apart from the others in a house in the black district. In Forgotten Tenor, trombonist Eddie Bert tells of the night when Goodman was absent during the dinner show, and Gray led the band while performing a send-up of the Goodman manner that had the musicians and the audience laughing. For a prop, he used one of Benny’s clarinets, loaned to him when the two had traded instruments at a New Year’s Eve party in New York. He had all the moves down, including the famous Goodman glare known as „the Ray.“ He was probably unaware that his boss happened to be dining in the room. Incensed, Goodman charged up to the bandstand, fired him in front of everyone, and then pursued him through the kitchen loudly demanding the return of his clarinet. The next day Goodman rehired him.

From all accounts, he got along well with his bandmates. In Swing, Swing, Swing, Ross Firestone’s biography of Goodman, however, Chico O’Farrill says that Wardell „sometimes felt the brunt of racial discrimination in a very strong way,“ and Buddy Greco claims that racism drove him from the band: „There were times when he couldn’t check into the hotel or eat in the restaurants. And then, when we worked down in Virginia, some Ku Klux Klanners burst into the little apartment Doug Mettome and I shared with him and threatened to lynch him . . . We had a lot of problems with racial situations and Wardell finally had enough.“

Forgotten Tenor features interviews with Wardell’s first wife, Jeri, and his widow, Dorothy. Both women speak of him as if the news from Las Vegas had come four months rather than 40 years ago. Asked about how he died, Jeri is still angry: „It was a bad death . . . Wardell died from a broken neck. He didn’t die from overdose of drugs, he died because he was left in the desert with his neck broken.“ Dorothy Gray reads aloud from some of the letters he wrote to her between 1950 and his death. In a 1951 letter, at the time he was leaving the Basie band and hoping to settle down in Los Angeles with Dorothy and his stepdaughter, he imagined how home life would be for them: „All working hard, studying, going to school, perfecting ourselves for one another. What a vast sense of accomplishment there will be in the atmosphere.“

While Charlie Parker and Lester Young were his most significant influences, Gray was no less inspired by the challenge of the many Los Angeles sessions where he played head-to-head with Dexter Gordon. „At all the sessions,“ Gordon told writer Stan Britt, „there would always be about ten horns up on the stand. Various tenors, altos, trumpets, and an occasional trombone. But it seemed that in the wee small hours of the morning—always—there would be only Wardell and myself.“ The two tenors turn up in On the Road „blowing their tops before a screaming audience that gave the record fantastic frenzied volume,“ and again when Dean and Sal play catch to „the wild sounds of Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray blowing ‚The Hunt‘ „—two heroes of the Beat generation playing along with two heroes of the swing-to-bop generation.

Their tenor battle in „The Hunt“ invites boxing analogies—Dexter the hard-hitting Joe Louis, Wardell the float-like-a-butterfly sting-like-a-bee Ali. Wardell comes out of his corner dancing while Dexter’s first moves are comparable to solid body blows, except the only body is the audience and in case anyone doubts the true nature of the event, his first quote is from the „Wedding March.“ The closest they get to a real punch-counterpunch confrontation is when Wardell begins the third round and Dexter breaks in briefly; when it’s Dexter’s turn, Wardell returns the favor with a quick, playful knock on Dexter’s door. As the other players begin riffing in the background, the excitement peaks with a loop-the-loop from Dexter followed by a move of Wardell’s that provokes an ecstatic shout from someone in the audience. Flights like this are what Mike Zwerin is getting at, in Close Enough for Jazz, when he writes that „the sound of Wardell“ with Basie’s big band at the Royal Roost in 1948 has never left his head—“I will go to my grave with it.“ Zwerin calls that sound „the cry“: „A direct audial objectification of the soul. You know it when you hear it.“

On those Central Avenue nights when they had people standing on tables and chairs cheering them on, Dexter and Wardell were so deep in tenor heaven they left the rest of the band behind. In Central Avenue Sounds, an oral history of L.A. jazz, pianist Gerry Wiggins reports that he and Charlie Mingus simply gave up and left the stage one night after the two tenors had been through 20 or 30 choruses „and they didn’t stop. They went right on with the drummer. Didn’t miss us at all.“

While it may seem to clash with the image of a hard-swinging, crowd-pleasing battling tenor, at least one writer has referred to Wardell Gray as a „princely“ figure, an image that is implicit in the critical language his playing inspires („rare grace and beauty,“ „elegant yet powerful“) and in photographs taken at various times in his life. He looks especially princely in a photograph of him smilingly enduring the playful embrace of Stan Hasselgaard, the Swedish clarinetist who played with him in Goodman’s septet and considered him „the best tenor in America today.“ In films of Basie’s small group made in 1950, Gray is the only musician who seems to have no time for the camera. Swaying along to the music, he shows such a tender regard for his instrument and for the act of improvising that when he steps forward to play his solos he looks less like royalty than a divinity student absorbed in prayer. Playing a courtly, warmly insistent preface to Helen Humes’s ebullient vocal on „I Cried for You,“ he treats the tenor as if one false or unfelt note would permanently wound it. The song of the Thin Man cries for us all.

http://www.villagevoice.com/2003-06-03/home/song-of-the-thin-man/

:: Ergänzung ::

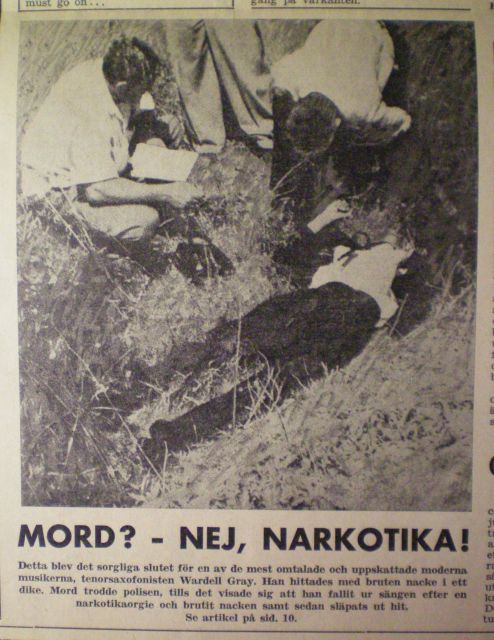

Aus der Juli 1955 Nummer des Schwedischen Jazz-Magazins „Estrad“.

Mehr dazu hier.

„ugly story, ugly foto“ ist wohl die beste Zusammenfassung des ganzen.

Aber zu Wardell Grays grossartiger Musik werde ich immer wieder zurückkehren!

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169: Pianistinnen im Trio, 1984–1993 – 13.01.2026, 22:00: #170 – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba