Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Sonny Stitt › Re: Sonny Stitt

Heute war Sonny Stitt Tag (und ist noch immer)…

The Hard Swing wurde im Februar 1959 aufgenommen mit Amos Trice am Piano, Lenny McBrowne am Schlagzeug und George Morrow am Bass. Wie auf den meisten Stitt-Alben jener Zeit gehört fast der ganze Platz dem Leader, der eine Reihe Standards in mittlerem und schnellem Tempo zum besten gibt, darunter „If I Had You“, „After You’ve Gone“ und „Street of Dreams“. Dazwischen gibt ein paar selbsterklärend betitelte Originals von Stitt: „Subito“, „Presto“, den Closer „Tune Up“, sowie das Highlight des Albums, den erdigen „Blues for Lester“. Trice und Morrow geben der Band einen schwereren Sound ans üblich, aber die Show gehört abgesehen von ein paar Piano-Chorussen und einem kurzen Bass-Solo in „Subito“ ganz dem Leader.

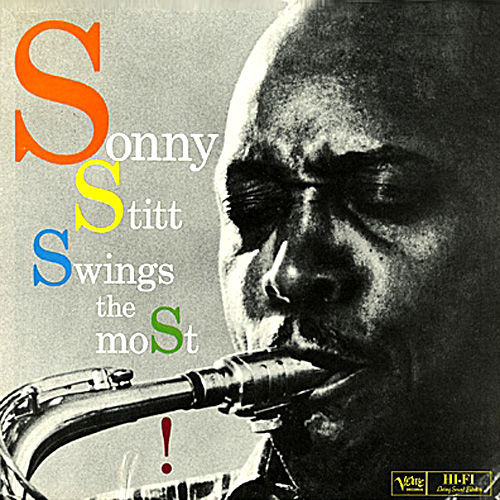

Erwähnenswert ist, dass nicht nur ein weiteres Stück dieser Session („That’s the Way to Be“ mit Gesang von Stitt) sondern auch „The Way You Look Tonight“ (der gleiche Take) auch auf dem Album „Sonny Stitt Swings the Most“ zu hören war – das Album ist Teil des erwähnten Fresh Sound Twofers Don’t Call Me Bird, dort fehlen allerdings die Infos dazu (es wird nur Lou Levy und die restliche Rhythmusgruppe der L.A.-Sessions vom Dezember erwähnt).

Im Dezember nahm Stitt an drei aufeinandernfolgenden Tagen in Los Angeles die drei Alben „Blows the Blues“, „Saxophone Supremacy“ und „Swings the Most“ auf (wie erwähnt enthielt letzgenanntes ein neues und ein bereits auf „The Hard Swing“ veröffentlichtes Stück mit Amos Trice vom Februar). Die beiden letztgenannten sind auf der Fresh Sound CD mit dem depperten Titel Don’t Call Me Bird versammelt – schöner wäre natürlich ein Set gewesen ähnlich dem West Coast-Set von Stan Getz, das teils mit derselben Rhythmusgruppe – Lou Levy (p), Leroy Vinnegar (b), Mel Lewis (d) – entstanden ist. Stitt klingt mit solcher Begleitung entspannt und locker, der Drang, jeden Standard, auch jene im langsamen Tempo, zu schnellen Stücken voller brillanter Läufe zu machen, ist etwas weniger deutlich zu spüren, Vinnegars Sound erdet die Musik enorm und Levy steuert ein paar sehr tolle Soli bei. Sehr schade, dass es keine gut gemachte Doppel-CD mit den Aufnahmen gibt (danke Fresh Sound).

Ein grossartiges Stück ist das lange „Lazy Bones“ mit tollem Stitt und einem sehr funky Solo von Lou Levy. Mit über siebeneinhalb Minuten Dauer ist es von diesen typischen Stitt-Alben eins der längsten Stücke. Levy steuert eine ganze Menge toller Soli bei und das lässt die Musik abwechslungsreicher werden. Stitt überzeugt – wie immer in den Jahren – am Alt und am Tenor gleichermassen. Am Tenor klingt er wärmer, der Ton ist grösser, weniger hart.

Only the Blues enstand im Oktober 1957 und ist ein atypisches Album: Stitt trifft auf einen anderen Jam-Heroen mit eisernen Chops, Roy Eldridge (der am selben Tag noch ein eigenes Balladen-Album mit Russell Garcia einspielte und an den Aufnahmen für Herb Ellis‘ Klassiker „Nothing But the Blues“ mitwirkte – soviel eben zu den Chops aus Stahl). Am Piano sass Oscar Peterson, seine Mannen (Herb Ellis und Ray Brown) waren mit dabei, ebenso Drummer Stan Levey. Die Stimmung ist geladen, die Bandd spielte vier lange Blues ein, ausser dem „Cleveland Blues“, bei dem Take 3 der Master wurde, alle nur in einem Take. Das kürzeste Stück ist der Opener „The String“ mit genau zehn Minuten Dauer, das längste der „Cleveland Blues“ mit zwölf Minuten. Die Funken fliegen nur so zwischen Eldridge, Stitt und Peterson. Das ist keine schöne Musik, sondern Musik, die eine einfache, direkte Sprache spricht, die direkt in den Bauch geht. Die CD-Ausgabe, die 1997 in der „Verve Elite Edition“ erschien, fügte die Stücke „I Didn’t Know What Time It Was“ und „I Remember You“ sowie diverse Takes von „I Know That You Know“ an – alle drei kurze Standards, klassisches Stitt-Material jener Zeit (Eldridge ist nicht zu hören). Ich kenne die Story dazu nicht, aber der Produzent im Kontrollraum bellt die Musiker förmlich an zwischen diversen False Starts und Breakdowns… vermutlich ist es Norman Granz, der auf der CD als Produzent angegeben wird. Spannung scheint nicht nur auf der musikalischen Ebene vorhanden zu sein.

Vom Mai 1957 stammt Personal Appearance, ein weiteres typisches Stitt-Album jener Zeit, dieses Mal mit dem jungen Pianisten Bobby Timmons sowie Edgar Willis (b) und Kenny Dennis (d). Das Programm besteht wieder zum grossen Teil aus Standards – darunter „Easy to Love“, „Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea“, „East of the Sun“ und „Avalon“ – sowie ein paar Originals („For Some Friends“, der abschliessende „Blues Greasy“ und das einfallslos betitelte „Original“). Insgesamt ein etwas verschlafenes Album… und man hört leider nicht viel von Timmons.

Aus Ira Gitlers „The Masters of Bebop: A Listener’s Guide“:

In 1946 Stitt also recorded excellent solos on That’s Earl Brother and Oop Bop Sh‘ Bam with Dizzy Gillespie. In 1947, he was voted the new star on alto by the critics and musicians of a poll conducted by Esquire magazine. By this time, however, he was not around to receive the acclaim that went with this. He was in the Federal Narcotics Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky.

When he was released in late 1949, Sonny returned to the jazz scene on tenor saxophone. While he did not give up the alto completely, he certainly de-emphasized it. From 1950 to 1952 he co-led a small band with Gene Ammons. This unit recorded for Prestige, as did Stitt on his won. The tenor „battles“ on Blues Up and Down and Stringin‘ with Jug with Ammons are creative as well as exciting. In the early sixties, Ammons and Stitt were reunited for a couple of club engagements and several records. By this time, however, Stitt was working on his own, but as a wanderer who would pick up a new rhythm section in each city he visited. Sonny also toured with JATP in 1958 and 1959, was reunited with Gillespie for three months in 1958, and played with Miles Davis in 1961 [er spielte schon im Herbst 1960 mit Miles – gtw]

In the sixties he was finally able to secure another cabaret card, the license that allows him to work in New York clubs. In a 1959 interview he told writer Dave Bittan, „I want to be in New York with my own combo. I’d like to get an apartment and make this city my headquarters. It was a long time ago when I got in trouble. I don’t want to talk about it. It’s a distasteful subject. I’m still paying for it. I was young . . . I didn’t know what it was all about. . . . My people were churchgoers and knew only the beautiful things in life. . . . They didn’t tell me about the bad things.“

[…]

Now [Gitlers Buch erschien zuerst 1966 unter dem Titel „Jazz Masters of the Forties“ – gtw] his playing time is divided between tenor and alto. He is equally adept on both, capable of high-velocity solos at medium and, especially, up tempos and of lyrical ballad expositions, although he does like to double-time on the latter. On tenor, his love of Lester Young shows through.

Stitt enjoys the challenge of a „cutting“ session with another saxophonist, and he is a hard man to best in such horn-to-horn combat. Possessing a combination of stamina and inventiveness, he seldom loses. Those who were at the Half Note on a particular night in 1961 will attest that he fell before Zoot Sims on Sweet Georgia Brown, but this is the exception rather than the rule. He has a justifiable price in his talent. Fellow saxophonist Stan Getz has said of him, „With Stitt, you’ve gotta work. He doesn’t let you rest. You’ve got to work or else you’ve left at the starting gate. It’s hard for me to say which horn he’s better on, alto or tenor.“

Al Cohn tells of an incident involving Getz and Stitt that is as illustrative as it is amusing. „Stan was playing at the Red Hill in Camden, New Jersey, and Sonny came by to sit in. He called a very fast tempo and took the first solo. By the time Stan got to play, the bass player’s hand was about to drop off. As soon as the number ended, Sonny packed up his horn and split. Stan said, ‚And he didn’t even give me a chance to get even with a ballad.'“~ Ira Gitler: The Masters of Bebop. A Listener’s Guide. Updated and Expanded Edition, 2001, p. 42-44

Gitler empfiehlt übrigens dann speziell die Alben „Personal Appearance“ und „Plays Charlie Parker“ (beides nicht grad meine Favoriten), erwähnt den Blues „Quince“ und Tadd Damerons „If You Could See Me Now“ von den Sessions mit Quincy Jones (Roost) sowie „The Eternal Triangle“ vom Album, das Dizzy Gillespie mit Stitt und Sonny Rollins eingespielt hat.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169: Pianistinnen im Trio, 1984–1993 – 13.01.2026, 22:00: #170 – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba