Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Abbey Lincoln – That's Her! (1930–2010) › Antwort auf: Abbey Lincoln – That's Her! (1930–2010)

Foto: Abbey Lincoln 1958 in London in ihrem Hotelzimmer

I think everybody suffers from stage fright at first. Some people, when they get to be older and elderly, still have it. I don’t know how. Yeah. I suffered from stage fright when I began to be presented as a star. Until then, I don’t remember ever suffering from stage fright. I worked at Ceros in Hollywood when I was named Abbey Lincoln. Sammy Davis had worked there. Many great stars, but the club was on the decline, and I auditioned for it. He didn’t really — he wasn’t impressed with me. I knew that because he said, „I’ve had it.“ But my manager talked to him and I opened that night and I trembled, I was so frightened at being at Ceros and I wasn’t anybody yet and I knew it and it was hard to sing.

So, I finally said to the audience, „I’m scared to death,“ and as soon as I said that, it relieved all the tension and I could do the performance, and I remember saying to Max a couple of years later, I said, „You don’t suffer from stage fright when you go to the stage.“ I said, „Why is that?“ He said, „Because I’m too busy preparing to be afraid.“ And I heard that, too.

I haven’t suffered from stage fright, I guess, since then. I’m not afraid anymore and I don’t come to impress anybody, but it is a preparation that you make when you come to the stage.

Als Abbey Lincoln Ende 1956 oder 1957 nach New York geht, ist sie eine Club-Sängerin mit einem eigenen Touch aber ohne grosse Originalität – und sie hat den Auftritt in „The Girl Can’t Help It“ im Gepäck, der ihr zusätzliche Aufmerksamkeit gab. Sie ist allerdings neugierig und intelligent und verkehrt bald mit einigen der interessantesten Jazzmusiker der Zeit, darunter die Pianisten Thelonious Monk und Mal Waldron (er war der letzte Pianist von Billie Holiday) und der Drummer Max Roach.

In Kalifornien hatte Lincoln ihre Manager und Agenten entlassen: „Because by now I had a manager who owned 50% of me. I overheard Bob Russell telling some people, ‚You don’t understand, I own this woman.‘ I fired everybody, agents, manager. I’ve not had a manager since. I’ve got business associates. But I manage myself!“. Auf Hawaii und in Kalifornien hat Lincoln sich einen Namen gemacht und keine Sorge mehr, dass sie nicht genügend Engagements kriegen würde. Max Roach hatte sie 1954 nach ihrer Rückkehr aus Honolulu kennengerlernt: „Friends had told him about me, that I was a singer he needed to hear. He was working with Clifford Brown at Hermosa Beach. I remember how beautiful his hands were. He encouraged me. I met Clifford that one time.“

I was working supper clubs and wearing this dress and bouncing on the stage, so my breasts would jiggle a little, but when you’re young, you know what I mean, you’re really naive and this is what my — I was — people who were helping me, my choreography and like that.

It wasn’t funny to me, though. I mean, I didn’t feel — I’ve always taken it seriously. So, it wasn’t easy to make light of my life like that. It was Max that told me „you don’t have to do that.“ He saved me, really, from myself. He helped to save me from myself, from all this that I was involved in.

I was learning. The first album I made with Max — well, my first album was with Benny Carter, Jack Montrose, and Marty Page, standards, that some of them — most of them Bob Russell had written. He was helping me and I was helping him.

Da waren wir ja bereits – doch es ist interessant, dass Lincoln ihr erstes Album bei Riverside als das erste empfindet, sich korrigieren muss, weil sie den eigentlichen Erstling vergisst. Und: die Parallelen der zwei Alben sind ebenfalls schwer zu übersehen: noch einmal erzählt „That’s Him!“ die Geschichte einer verliebten Frau. Allerdings wird sie jetzt von einem hervorragenden Jazz-Quintett begleitet, alles ist perfekt abgestimmt, als Album funktioniert das alles prächtig. Doch dazu kommen wir gleich.

Wie war es, in der Zeit nach New York zu kommen?

Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra were working at the Copacabana and the Village Vanguard was the space for developed unknown artists, like Enid Mosier, Abbey Lincoln, Mae Barnes, a chic little room, and Max Gordon also was a part-owner of Blue Angel, a nightclub that also presented people of this type, and it was the first time I saw Lena Horne […] and it was a changing point in my life. I’d never seen her in person, and I’d been compared to her. They compared everybody to Lena then. Barbara McNair, Diahann Carroll. I saw this absolutely original woman on stage who sang „Evil Spelled Backwards means Live.“ She was brilliant. Changed my life. I knew that I was never going to be anything like Lena. I was just going to be myself, like she was herself.

Lincoln verbringt ihre Zeit mit Max Roach, Maya Angelou und anderen. Cab Calloway bietet ihr einen Job im Central Park an, wo sie Sammy Davis und Frank Sinatra wieder antrifft, „the Rat Pack they called them. Wonderful men.“ Auch Ellington und Armstrong, die sie in Honolulu traf, sind in New York. Sie tritt im Village Vanguard auf – und äussert sich im Gespräch 1996 sehr deutlich und vielleicht etwas überraschend über diesen legendären Jazzclub

They had a kitchen then and they also had a dressing room right off the stage […]. When they decided to bring jazz into the room, they eliminated the dressing room and they finally closed the kitchen and they never scrubbed the floor. I hate jazz rooms.

I heard Sarah Vaughan say that once and I knew a lot of people didn’t understand what she was talking about. I hate being treated second class in the name of pretending to be romantic. That’s supposed to be sexy, that I’m in the corner in the dark. It’s part of the grief of being a part of this music.

Für Riverside entstehen drei Alben, je eines in den Jahren 1957 bis 1959. Max Roach agiert, wie Lincoln es ausdrückt, als ihr „A&R man“: Er stellt die Kontakte her, wählt die Musiker aus usw. Das Material selbst trägt wieder ihre eigene Handschrift.

Das erste Album heisst That’s Him! und präsentiert Lincoln erneut im tief ausgeschnittenen Kleid und mit geglättetem Haar – auch in der Hinsicht gar nicht weit vom Debut auf Liberty entfernt. Die Musik wird am 28. Oktober 1957 eingespielt: Eine Session, 10 Stücke (später kommen noch zwei Alternate Takes heraus), von denen aber eines nur auf einem japanischen LP-Reissue von 1976 erscheint.

Eine Phrase von Sonny Rollins, dann: „I’m in love with a strong man / And he tells me he’s wild about me. / I’m in love with a guy who’s everything grand /Any man can be“. Die Versuchung ist natürlich sofort da, das Album als biographisches Narrativ zu lesen. Doch passender scheint es, „That’s Him“ als zweiten Anlauf der Story zu deuten, die Lincoln für „Affair“ entwickelt hat (siehe oben): Eine verliebte Frau singt über ihren Mann, ihre Gefühle, ihren Mann, stellt auch ein paar Fragen, singt über ihren Mann – so in etwa. Und dann singt sie noch über ihren Mann. Es gibt durchaus ein paar Fragezeichen, und die eigene (vielleicht etwas später einsetzende?) Gewaltgeschichte mit Roach ausblenden fällt auch schwer bei dem Programm, selbst wenn Lincoln im Gespräch von 1996 zum Song „Happiness is just a thing called Joe“ betont: da gehe es ja um ein Ding: „When I was in trouble when I was looking for myself, I sang these other songs. ‚Happiness is Just a Thing Called Joe,‘ not a man, a thing.“

Manche Songs werden zu Minidramen, in denen die Musik den Text gleich umsetzt. Rollins klingt wahnsinnig schön, oft wie durch einen Samtvorhang – und dennoch wie in Stein gemeisselt. Inwiefern das alles nun noch von der Naivität beherrscht ist, die Lincoln im Rückblick ihrem damaligen Selbst attestiert, ist schwer zu beurteilen. Ich halte auch die Lesart eines lustvollen Spiels mit Rollen und Konventionen durchaus für möglich. „He’s not an angel / But I don’t care“ singt sie in „I Must Have That Man“ – in dem die Band im rasenden Tempo ihre Bebop-Chops unter Beweis stellen und auch Roach mächtig aufdrehen kann.

Und dann ist da – einst an zweitletzter Stelle der A-Seite der LP, vor dem Titelstück – das unbegleitete „Tender as a Rose“, das dann je nachdem auch wieder unterschiedlich gelesen werden kann. Joe kommt da auch wieder vor – quasi als der düstere, böse Gegenpol zum Ich, das eben zart wie eine Rose sei. Die Ambivalenzen, die sich hier auftun – direkt im Material, in Lincolns Interpretation und besonders im Rückblick und nach Lektüre von Lincolns eigenen rückblickenden Aussagen – sind jedenfalls mannigfaltig und nicht ganz leicht auszuhalten. „She came back walking all alone. / She wasn’t gone for very long. / She came back with a heart of stone. / We knew that everything gone wrong. / And when you we ask her why she’s out each night. / She’ll say ‚Brother, once I tried to be right / Once all of my lovin‘ was Joe’s. / I was as tender as a rose.‘ / She was as tender as a rose.“

Musikalisch markiert Sonny Rollins nicht nur im Opener den „strong man“ des Albums, Kenny Dorham mit seinem lyrischen verschatteten Trompetenspiel den sanften Gegenpart – die beiden waren davor Kollegen in Roachs Band. Dieser spielt natürlich das Schlagzeug. Paul Chambers von Miles Davis‘ Band ist am Bass dabei, und ein künftiger Davis-Sideman sitzt am Klavier: Wynton Kelly – bereits ein gestandener Begleiter von Sängerinnen. Bei ihm laufen die musikalischen Fäden zusammen: „I worked with Wynton Kelly for awhile after he left Dinah [Washington]. Dinah cried about it, too. She really loved Wynton. She really complained when he left.“

Hier ist das auf der LP (und auch allen herkömmlichen Reissues) fehlende Stück, „Can’t Help Lovin‘ That Man“ – präsentiert als Rubato-Ballade mit blumigem Klavier von Wynton Kelly und Arco-Bass von Paul Chambers:

Billie Holiday ist im Album immer wieder präsent. In vielen kurzen Momenten, was Lincolns Gesang angeht, aber auch im Repertoire mit „My Man“, „I Must Have That Man“ und besonders dem Closer, ihrem eigenen „Don’t Explain“. Wie auf dem Debut verkörpert Lincoln hier eine Opferrolle, wie sie sie später ablehnen sollte – und ist dem in manchen Kreisen wohl gerade deshalb so berühmt gewordenen Vorbild deshalb sehr nah. Im Gesang bleibt da und dort eine Härte – oft im Vibrato am Ende von Phrasen oder auch mal zwischendurch in langen gehaltenen Tönen. Doch selbst wenn man das Album als zweite Runde der „Affair“ lesen wollte: Es ist dennoch ein paar grosse Schritte davon entfernt. Ein gutes Jazzalbum mit einer hervorragenden Band, die sich auf die Sängerin einlässt, sie kongenial begleitet – und das funktioniert für meine Ohren wirklich nahezu perfekt. Auch die Abfolge der Songs, die Tempi usw.: das ist ein perfekt programmiertes und arrangiertes Album. Ein kleines Detail: Auf „Don’t Explain“ ist Chambers nicht dabei und Kelly wechselt vom Klavier an den Kontrabass. Und wenn Kelly im Stück davor, „When a Man Loves a Woman“, einsetzt, klingt er im ersten Moment exakt wie Oscar Peterson.

Roach gegenüber hat Lincoln sich stets sehr dankbar gezeigt. In Amiri Barakas „Digging“ sagt sie:

„Influences? Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington-I had a lot of influences. But Max Roach was the main influence. I was still wearing that Marilyn Monroe dress, and one time in Canada, Max says, ‚Abbey, I don’t like that dress.‘ I thought about it then put it in the incinerator so I wouldn’t wear it again.

Max and the great musicians he introduced me to knew everything about theory. He introduced me to the cycle of fifths in B-flat. What I love about this music is the promise of individuality. Variations on a theme. If you can get past the idea of jazz,“ Abbey hisses the word into a chuckle. The dismissal of the term as a loose straightjacket of commerce and cultural patronization is one she shares with Roach, who told me he got it from Duke Ellington.

[…]

„But when I met Max I understood what I was involved in. He asked me, ‚Abbey, why do you sing everything legato? This is a rhythm music. On the beat!‘ He’d say that even on the stage.

How would I have gotten a chance to meet these great musicians-Rollins, Dorham? Max asked me, ‚Abbey, would you like to make a jazz album?‘ I told him I wasn’t a jazz singer. He said, ‚You’re black aren’t you?‘ The Riverside dates came out of that [That’s Him, Abbey Is Blue].“

With another smiling irony, Abbey remembers, „That’s when the jealousy started.“ And to my interrogator’s incredulousness, she adds, „Uh huh, people were jealous. I wasn’t supposed to be taken seriously,“ her tone stiffening. „I would get this from singers. They’d be talking to Max, ‚Why don’t you let Abbey go make some money, she’s not a singer!‘

But Max and the other great musicians he introduced me to carried me through all that.

Zum Thema der „jealousy“ mehr im folgenden umfassenden Post.

Im Gespräch mit Sally Plaxson 1996 erinnert Lincoln sich auch nochmal an den „Circuit“, auf dem sie bis dahin unterwegs gewesen war – und den sie mit dem Gang nach New York und der Zusammenarbeit mit Roach verlassen hat (aus der Passage stammt auch das oben schon verwendete Zitat zu Dinah Washington und Wynton Kelly):

SALLY PLAXSON: Maybe we can, for just a minute, jump back to talking about venues. You talked yesterday about Salt Lake City and the whole Northern Pacific. Was it a circuit? What was the –

ABBEY LINCOLN: Yeah. It was a circuit.

SALLY PLAXSON: How did you travel?

ABBEY LINCOLN: Denita Joe [Damita Jo, eigentlich Damita Jo DeBlanc] and Vivian Dandridge, Dorothy’s sister, people who were not names. There was a circuit. Salt Lake City, Roseburg, Oregon, and finally Honolulu, some places in Japan. I never went to Japan, but those were the places I went.

[…]

SALLY PLAXSON: So, how would you travel? How would it — how long would you have?

ABBEY LINCOLN: The best we could. By bus, by car. The least expensive way. When I started to make a $100 a week in Honolulu, I thought wow, I didn’t know there was all this money in the music, you know. I worked as a maid and I had made like $30 a week which was pretty good for a maid in that time.

But I was making a $100 a week, finally a $150 a week. It’s a privileged lifestyle, really, even though I complained about it. We are honored, the ones who come to the stage and have the courage to stay there. The people come and they bring you their money and they give it to the producer and the producer gives it to us and some of us live wonderful lifestyles. It’s because of the people. The producers give us nothing. It’s an advance on what the people bring.

It’s the people who make us rich. I think they deserve a lot more than they get. The people. I don’t know why they pay for this garbage. A lot of it’s garbage. They could do better themselves in the living room.

SALLY PLAXSON: Did this network go into Canada, too?

ABBEY LINCOLN: No. When I became more famous, when I became Abbey Lincoln, and I had this movie, „The Girl Can’t Help It,“ they started to send me to Canada, to England, to Sweden, places like that, and to Miami Beach.

SALLY PLAXSON: Did you travel with your own group? How did that work?

ABBEY LINCOLN: No. That was one of the disadvantages. I started to travel with my own band when I became a jazz singer. When I recorded the first album I made with Max and Kenny Dorham and Sonny Rollins and Wynton Kelly and Paul Chambers, I knew I was never going back to doing what I had been doing. I was going to work with these kind of musicians.

SALLY PLAXSON: Why did you know that? What about it made you know that?

ABBEY LINCOLN: It wasn’t anything hard to figure out. They were great musicians and they enhanced my abilities on the stage. Yeah. I thought okay, this is what it is. Somebody who knows how to interpret a song, who knows the difference between A flat and C sharp. Yeah. Sophisticated man at the piano or on whatever. Mm-hmm. Yeah.

SALLY PLAXSON: So, when you were on the circuit before you got to the point you

were, it was the bands at the clubs or whoever?ABBEY LINCOLN: I would be sometimes the only black person in the room. They didn’t want black people to come and visit, like in Miami. A black man would frighten them. You’d see somebody sweeping the floors sometimes. I was surrounded by whites and they were the band leaders and they were the band, the piano player, but they didn’t think of themselves as great musicians. It was just a job, you know, and sometimes it was really difficult and sometimes it wasn’t too bad, but usually it was a drag, and I started traveling with just a piano player.

I worked with Wynton Kelly for awhile after he left Dinah. Dinah cried about it, too. She really loved Wynton. She really complained when he left.

Anyway, I worked with Wynton in Brooklyn and a few places. Big, Big Nicholas, big Nick Nicholas.

SALLY PLAXSON: Big Nicholas? [Big Nick Nicholas, eigentlich George Walker Nicholas, Widmungsträger von Coltranes „Big Nick“]

ABBEY LINCOLN: I shared the bill with him in Brooklyn and I started working with Phil Wright, Junior Manson [Junior Mance], and Phil and I would go out on the road, just him and me, but I started carrying a band when I was with Roach. I worked with him as his girl singer, but every once in awhile, I mean, I had a band.

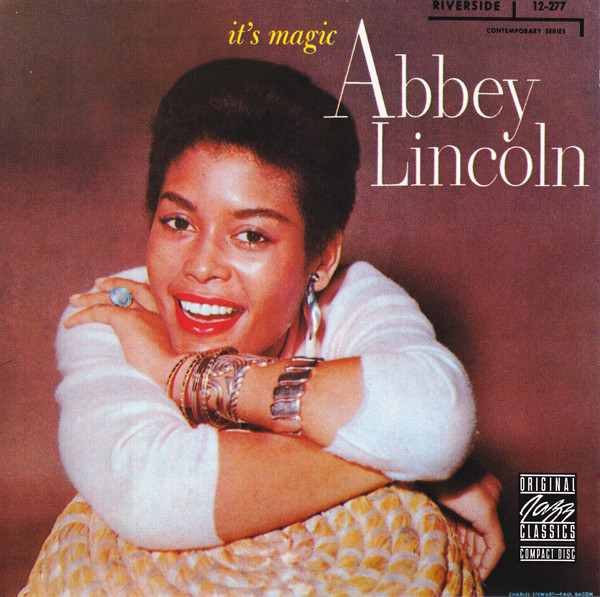

Für das zweite Riverside-Album, It’s Magic (1958), wurde auf das Sexy-Cover verzichtet, das Haar ist weiterhin geglättet. Zwei Sessions Ende Juli und Ende August werden abgehalten, die Band ist etwas grösser, Benny Golson zeichnet für die Arrangements verantwortlich und spielt auch gleich mit. Wynton Kelly sitzt wieder am Klavier, Philly Joe Jones übernimmt am Schlagzeug. Bei der ersten Session sind auch Kenny Dorham und Paul Chambers wieder dabei, die bei der zweiten von Art Farmer und Sam Jones abgelöst werden. Bei beiden Sessions entstehen Stücke mit Quintett (wie für „That’s Him!“) und welche im Septett, wofür Curtis Fuller an der Posaune und Jerome Richardson bzw. Sahib Shihab an Flöte und Baritonsaxophon dazustossen.

Zehn Stücke, fünf mit kleiner, fünf mit grosser Band sind das Ergebnis. Es geht natürlich auch hier wieder um die Liebe – aber nicht nur. Cole Porters „I Am in Love“ ist der Opener der Albums, gefolgt vom Titelstück. Lincoln klingt souveräner, entspannter, zum Beispiel in „Just for Me“ (ein „novelty tune“ gemäss Produzent Orrin Keepnews in den Liner Notes). Das hat auch mit dem so anderen „feel“ von Philly Joe Jones zu tun, dessen Time deutlich flexibler ist als die von Roach. Die Arrangements sind viel enger gehalten als auf dem Vorgänger, manches wirkt etwas süss und gepflegt – den Eindruck verstärkt auch Golsons weicheres Tenorsaxophon. Dennoch: Lincoln wirkt anders, nicht nur souveräner, auch stärker, selbstsicherer – zum Beispiel in „An Occasional Man“, einem der Höhepunkte des Albums (Jeri Southern lässt grüssen). Die Bläser sind klasse arrangiert, die Rhythmusgruppe deutet im langsamen Tempo wieder eine Art Tango an – und Lincoln phrasiert darüber wahnsinnig gekonnt. Auch ihr Vibrato kragt hier nicht mehr so weit aus, klingt kontrollierter und klangschöner.

Wynton Kellys Rolle ist in dem Kontext weniger bedeutsam – Golson hat das alles im Griff und weist Kelly halt auch seine Parts im Gefüge zu. Für Jazzfans mag das auch etwas frustrierend sein, denn die Stücke sind meist wieder kurz gehalten und die hervorragenden Begleiter sind nur selten und meistens auch nur kurz zu hören. Ein Intro da, ein Obbligato dort … in der Hinsicht ist das vielleicht näher am ersten Album für Liberty – doch kommt hier das beste aus beidem zusammen: die Arrangements sind dieses Mal auf Lincoln abgestimmt, gespielt werden sie von exzellenten Jazzern, die eine ganz andere Souveränität im Umgang mit dem Material an den Tag legen als die anonymen Studiobands (sicherlich auch voller Jazzer) in Kalifornien. Und dann ist da eben eine hörbar reifer gewordene Lincoln. Auch schon zu hören ist „Ain’t Nobody’s Business“, das Lincoln gut zwei Jahre später erneut einspielen sollte, dann als ihr Beitrag zum Album der „Newport Rebels“ auf Candid – doch das ist dann das nächste Kapitel der Geschichte. Sehr locker wirken alle in „Exactly Like You“ im Quintett – mit hervorragenden kurzen Soli von Golson und Dorham, und einem funky aufspielenden Kelly.

Die beiden bemerkenswertesten Songs des Albums sind von Jon Hendricks getextet: „Out of the Past“ (Musik von Benny Golson) am Anfang und „Little Niles“ (Randy Weston) am Ende der zweiten Seite des Albums. Laut Keepnews hat Lincoln „Out of the Past“ ins Studio mitgebracht, ohne dass Golson im Vorfeld davon wusste. Vielleicht darf man das als leisen Vorboten der bald folgenden eigenen Songs deuten. Zu den Highlights der zweiten Seite des Albums gehört neben dem bezaubernden Closer „Little Niles“ auch Lincolns Version von „Music, Maestro, Please“.

Im September ist Lincoln dann wohl wieder mal in Hollywood, jedenfalls werden auf den 29. (das mag das Datum der Ausstrahlung sein, nicht der Aufzeichnung) zwei Stücke datiert, die auf der LP „Sessions, Live“ (Calliope 3009) erscheinen: „Out of the Past“ und „When a Woman Loves a Man“ mit der Band von Buddy Collette: Buddy Collette (fl, as), Gerald Wilson (t), Al Viola (g), Red Callender (b), Earl Palmer (d). Leider kann ich die zwei Stücke in der Tube nicht finden.

Für das dritte und letzte Riverside-Album sind mehrere Sessions nötig, die sich von März bis November 1959 hinziehen. Abbey Is Blue heisst es, auf dem Cover ein Close-Up der singenden Lincoln – ein starkes Bild. Und passend dazu geht es mit „Afro Blue“ unglaublich stark los. „Brown-Mann“ steht auf der LP, aber nicht Herbie Mann hat das Stück komponiert sondern natürlich Mongo Santamaria. Brown, das ist Oscar Brown Jr., dessen Zusammenarbeit mit Max Roach und Abbey Lincoln in dieser Zeit beginnt. Dieser Auftakt ist eine Ansage, ein Statement. „Dream of a land my soul is from / I hear a handstroke on a drum. / Shades of delight / Cocoa hue. / Rich as the night / Afro blue.“ Die Bläser punktieren und legen lange Linien, der Kontrabass trägt das Stück praktisch allein, während Roach ausschmückt und dann beim Trompetensolo für etwas Drama sorgt. Sehr catchy, sehr eigen, sehr stark.

Wie bei den anderen drei Stücken vom November 1959 wird Lincoln hier von der damaligen Band von Max Roach begleitet. Seit dem Tod von Clifford Brown und Richie Powell leitete dieser klavierlose Combos, zog aber hie und da für Plattensessions Gastpianisten bei. Hier ist das Cedar Walton, der das Quintett ergänzt, das aus den Turrentine Brüdern (Tommy an der Trompete, Stanley am Tenorsaxophon), dem Posaunisten Julian Priester und Bob Boswell am Kontrabass besteht.

Das zweite Stück des Albums – das einzige von einer Session im Mai mit Dorham, Kelly, Les Spann (g), Sam Jones und Philly Joe Jones – ist eine langsame Nummer von Kurt Weill mit einem Text von Langston Hughes, „Lonely House“. Auch hier gibt es ein tolles Arrangement, der Kontrabass spielt einen Orgelton auf den ersten Schlag jedes Takts, Roach schlägt auf der kleinen Trommel die Viertel durch, erst nach über einer Minute steigt das Klavier ein, der Bass deutet jetzt alle zwei Schläge die Changes an, die Bläser kommen im Hintergrund dazu. Das ist ein exquisites Mood Piece („even stray dogs find a friend … the night for me is not romantic …“) – mit der „Affair“ hat das erstmal gar nichts mehr zu tun – der Neuanfang bestätigt sich. Und das bleibt so, denn an dritter Stelle folgt mit „Let Up“ das erste eigene Stück, das Lincoln aufgenommen hat. Walton und das Roach Quintett sind auch hier zur Stelle, der neu gefundene Tonfall bleibt, selbst wenn es wieder einmal um das Unglück geht: „Let up! Let up! Let Up! When will trouble let up. / This heartache is dragging me down“ – und Tommy Turrentine ist auch hier im Hintergrund wieder umwerfend, während erneut Boswell das Stück trägt.

Bei zwei Sessions im März 1959 entstand die erste Hälfte des Albums, Dorham, Spann (Flöte und Gitarre), Sam Jones und Philly Joe Jones waren auch da schon mit dabei, am Klavier bei der ersten Session Phil Wright, bei der zweiten wieder Kelly. Auch hier gibt es ganz viele wunderbare Details in der Musik zu hören, zum Beispiel die Gitarren-Verzierungen von Les Spann in „Thursday’s Child“, dem ersten der fünf Stücke vom März, das bei der zweiten Session entstand, zusammen mit dem die erste Albumhälfte beschliessenden „Brother, Where Are You?“, für das Oscar Brown Jr. nicht nur den Text sondern auch gleich die Musik beigesteuert hat. Sein „Hum Drum Blues“ und Henry Glovers „I’ll Drown In My Own Tears“ blieben leider unveröffentlicht (seltsam und bei Fantasy-Reissues sonst unüblich: statt dem fehlenden Master “ Can’t Help Lovin‘ That Man“ gab’s für die OJCCD von „That’s Him!“ zwei Alternate Takes – „I Must Have That Man“ und „I Loves You Porgy“ – und auch hier wurde mögliches Bonusmaterial verschmäht).

Das einzige, was man dem Album vielleicht vorwerfen kann, ist eine gewisse Gleichförmigkeit: auch in Browns „Brother“ gibt es Pedal Points vom Bass, feine four-to-the-bar-Drums von Roach – doch das Klavier von Kelly und die Flöte von Spann im Hintergrund bringen wieder einen anderen Touch rein als die drei Bläser bei der Session vom Herbst. So wirkt das Album für meine Ohren im relativ engen Rahmen, den es sich steckt, eben doch sehr abwechslungsreich: und wirklich voller wunderbarer Details, die ein genaues und wiederholtes Hören lohnenswert machen.

Die zweite Albumhälfte besteht aus einem Opener und Closer vom November und dazwischen den drei Stücken von der ersten März-Session mit Phil Wright am Klavier. „Laugh, Clown, Laugh“ ist ein mittelschnelles Stück, das ohne Orgelpunkt-Bass auskommt – Tommy Turrentine ist auch hier wieder toll! Wie bedauerlich, dass er nicht bekannter wurde und mehr eigene Aufnahmen machen konnte. Dem traurigen Clown hatte Mingus auf „The Clown“ ein langes Stück mit Rezitation gewidmet, Lincoln singt das hier sehr gradlinig – und fällt für meine Ohren etwas zu sehr in ihr altes Vibrato zurück. Dennoch: die Sängerin hier ist auf dem Weg, sich neues Territorium zu erschliessen – das wird wirklich auf jedem Stück des Albums deutlich.

Das Segment vom März besteht aus „Come Sunday“ aus Ellingtons „Black Brown & Beige“-Suite, dem Standard „Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise“, und „Lost in the Stars“, dem zweiten Beitrag von Kurt Weill (Text von Maxwell Anderson). Spann spielt hier nur Gitarre – und seine Verzierungen, Arpeggi und Melodien im Hintergrund sind klasse.

Nach diesem eher konventionellen und nichtsdestotrotz starken Segment endet das Album dann mit einem weiteren Original, „Long As You’re Living“, geschrieben von Julian Priester und Tommy Turrentine im 5/4-Takt, mit Lyrics von Oscar Brown Jr. Hier ist das Schema wieder: Boswells Bass trägt den Groove, Roach füllt, die Bläser riffen ein wenig – Walton setzt aus (wie schon im Opener „Afro-Blue“, was dem Album eine weitere Symmetrie gibt). Ein kurzer Abschluss in einem tollen Groove – und ein echt starkes Album, das die Tür zum nächsten Kapitel öffnet: der engen Zusammenarbeit mit Max Roach.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #169: Pianistinnen im Trio, 1984–1993 – 13.01.2026, 22:00: #170 – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba