Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Abbey Lincoln – That's Her! (1930–2010) › Antwort auf: Abbey Lincoln – That's Her! (1930–2010)

Im selben Jahr, in dem Lincolns Aufritt für „The Girl’s in Love“ (s.o.) aufgezeichnet wird, nimmt sie auch ihr erstes Album auf. Doch ein paar Monaten davor, im Juli 1956, entstehen sechs Stücke, die vielleicht fast von grösserem Interesse sind. Nur zwei von ihnen kommen damals als Single heraus, auf zwei weiteren wird sie nur von Gitarre, Vibraphon und Kontrabass begleitet: „Warm Valley“ (Ellingtons Vulva-Song mit Lyrics von Bob Russell) und „You Do Something to Me“ von Cole Porter. Lincoln klingt in „Warm Valley“ für meine Ohren etwas verhalten, auf jeden Fall zurückhaltender als mit ihrem deklamatorischen Cabaret-Stil im Film. Im Porter-Song klingt ihre Stimme offener – aber der ist praktisch vorbei, kaum hat er angefangen.

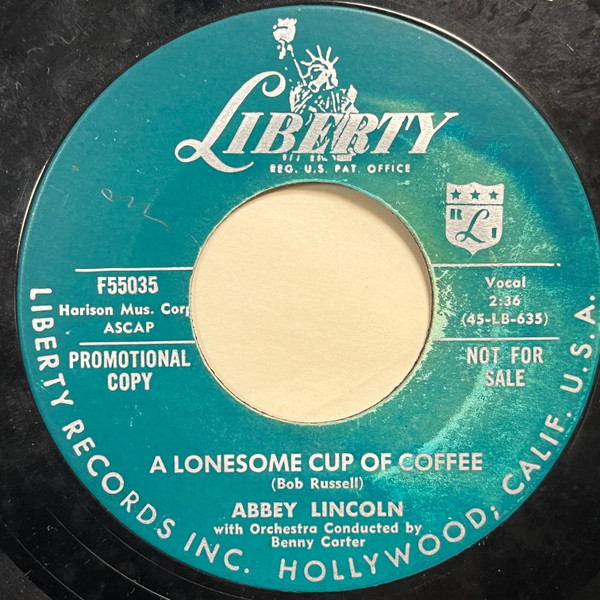

Noch bei zwei weitere der sechs Stücke hatte Russell seine Finger im Spiel – und klar gibt es da ein Machtgefälle. Ich denke, diese Problematik konnte im Musikbusiness (vom Film schweigen wir besser mal, oder?) bis heute nur sehr selten halbwegs gelöst werden. Gelöst ist da ja nur, wenn auch die Umstände der Produktion und die Vertriebskanäle anders organisiert werden können. Und es ist ein Thema, das auch hier im Forum schon zu Friktionen geführt hat (weniger in der Jazzecke glaub ich), weil auch die Mehrzahl der Fans lieber nichts davon wissen mag, was allers hinter den Kulissen passiert. Lincoln ging damit aber später sehr offen um. Sie singt Ellingtons „Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me“ mit Russells Lyrics, „The Answer Is No“ von Harold Levey, und dann – auf dem CD-Reissue des Debutalbums von 1993 an den Schluss gestellt – die zwei auf einer Single veröffentlichten „Lonesome Cup of Coffee“ (hier hat Russell gleich Text und Musik geschrieben) und „She Didn’t Say Yes“ (als „I Didn’t…“) von Jerome Kern/Otto Harbach.

Benny Carter hat die vier Stücke arrangiert, durchaus attraktiv und abwechslungsreich, wenn man die vier zusammen nimmt. In Russells Song gibt es eine Altflöte, gedämpftes Blech (leise Ellington-Anklänge – wobei bei Carter solche Vergleiche eh ins Leere gehen: das ist fucking Benny Carter!), ein tingelndes Klavier, einen rollenden Bass, ein paar Rim-Shots – und eine ziemlich toll aufgelegte Lincoln:

Am 5. und 6. November 1956 entstand dann das Debutalbum, auch wieder für Liberty Records. Produziert hat Russell Keith, aber die Fäden gezogen hat Bob Russell, von dem ein Song („Affair“) komplett stammt, während er zu vier weiteren (es gibt 12, das ist Konfektionsware) die Texte schrieb (Ellington, Camarata, Sigman, Harold Spina). Daneben gibt es Gershwin, Rodgers/Hart usw.

Aus dem Gespräch mit Sally Plaxson von 1996:

I was learning. The first album I made with Max — well, my first album was with Benny Carter, Jack Montrose, and Marty Page, standards, that some of them — most of them Bob Russell had written. He was helping me and I was helping him.

[…]

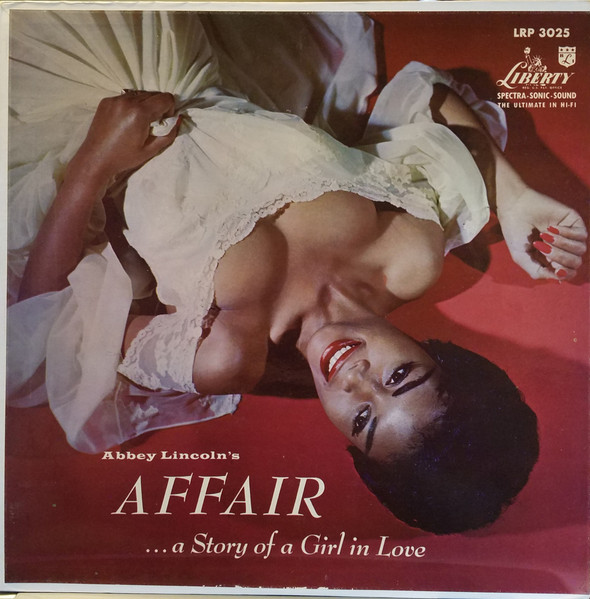

The name of the album was „Affair: Story of a Girl in Love,“ and they photographed me upside down with my breasts spilling out in this negligee, this yellow negligee, on a label called Liberty Records. Bob thought that they were going to laugh when they saw a picture of Abbey Lincoln superimposed over Abraham Lincoln looking like a tart, but nobody got it. It wasn’t funny to them. I heard one woman at the bank laugh. „Abbey Lincoln.“ That’s the only reaction. They used a picture of a penny and superimposed my image over it in Marilyn Monroe’s dress. Nobody got it, and wrote this song for me to sing in „The Girl Can’t Help It,“ „Spread The Word, Spread the Gospel, Speak the Truth, It Will be Heard Wearing this Dress.“ It was really contradictory, you know. It could have taken me out, too. I got passed that.

Ich verstehe leider die Beschreibung des Covers („they used a picture of a penny and superimposed …“) überhaupt nicht.

Auf die Frage, ob sie sich damals bewusst gewesen sei, wie diese Bilder von ihr wirkten, verneint sie (was gegen meine obige These zu Baraka usw. spricht):

No. It was my first time. How would I have known? I hadn’t wished to be a star. I can honestly say that. I always dreamed of a man. I didn’t dream of children, but I was going to meet this god who was going to save me from myself. I didn’t dream of being a star or being a movie star or any kind of other star. I still don’t care anything about it. But I think it just was my lot because I’ve had plenty of chances to be a super star. They can give it to their mother. I don’t want everybody to know my name.

Bob Russell wählte die Musiker und steuerte einiges an Material bei – doch Lincoln sagt im Gespräch von 1996, dass sie grundsätzlich die Songs ausgewählt und auch die Story des Albums, die „Affair“, entwickelt habe: „the love story of a girl, a love song, a love story that goes bad because all I ever knew was about a love affair that went bad, and so because I’ve always picked the songs I would sing, people don’t pick my material. They may pick the musicians, help me pick the musicians, but I pick the songs.“

Dieser Kontext ist heute Gold wert, denn Russells Liner Notes wären ohne ihn inzwischen zumindest teilweise recht schwierig (und sie bleiben es im patronisierenden Tonfall auch mit dem Kontext noch). Doch er äussert sich auch zu seinem Verständnis von Songs – und davon verstand er ja tatsächlich etwas. Ich tippe die Liner Notes rasch ab, sie sind kurz und füllen nochmal einige Details aus der Zeit (1954-56) ein, die in den anderen mir vorliegenden Texten fehlen. Und alles in allem ist das doch ein schöner Text, der viel Wertschätzung ausdrückt. Natürlich enthält der Text auch einiges an Promo-Sprech – aber er liegt in vielem ja auch goldrichtig, zumindest wenn man es nicht auf „Affair“ sondern auf das, was danach folgen sollte, bezieht.

AFFAIR … The story of a girl in love … told by Abbey Lincoln … in song. Songs, good songs, have something to say. They hava a beginning, a middle and an end, as in life, and are a facet of life itself. Any real-life situation involving people is a series of scenes as in a play – so our album which uses the dramatic technique of the song to forward and develop the action and tell the story of a woman looking for love. This story-telling with songs for scenes may very well be an innovation in album planning.

Let this album, then, be your calling card to the poignant memory of a new romance, its bright hope of „this time – now,“ its sad clinging to what might have been, its almost … its … its

As the cover of this album would indicate, Abbey Lincoln has been blessed with the lines, curves, arcs and semi-circles in the tradition of classic beauty. Anything said would be superfluous. One photograph bespeaks a thousand words.

However, Abbey possesses qualities her picture can only suggest. If she could reach out and touch you as she almost does with her smile, or warm you as she can with the glow and sometimes fire in her eyes, you, too, might get caught up in the web.

There is a vitality about her a vibrancy a directness; an intelligence – all of which is reflected in the type of song she sings and the way she handles the lyrics, which lets you know she has been there once or twice before. She also knows you’ve been there once or twice yourself.

Chicago-born, Kalamazoo-bred, jazz band trained and honky-tonk educated, Abbey landed in Los Angeles in October 1954 after a year-and-a-half singing stint in Honolulu. Then for the next year, she was the production singer at the lavish Moulin Rouge.

In September 1955 Abbey struck out on her own. „Struck out“ in this case is an apt phrase. The following ten months were disheartening. It was one step forward and two steps back. Then, suddenly, the background, the years of experience, the opportunity all began to mesh. After an audition, she was booked in June 1956 for two smash weeks at the world-famous Ciro’s in Hollywood and was signed exclusively by Liberty Records who released her first record „Lonesome Cup of Coffee“ and „I Didn’t Say Yes“ to synchronize with her even more successful return engagement at Ciro’s in September 1956.

During this time she appeared on several coast-to-coast TV programs, became Oscar Levant’s vis-a-vis on his tremendously popular local TV show and guest starred in Twentieth Century Fox’s „The Girl Can’t Help It.“ This was followed by three weeks of „standing room only“ at Beverly Hills‘ new Ye Little Club and then to the Copacabana in Rio De Janeiro, followed by one month at Chicago’s Black Orchid.

Abbey get around but that’s because she’s on her way. If she happens to pass your way – stop, look and listen. You’ll be entranced.

~ Bob Russell

Detail, weil ich selber grad etwas ungläubig war: ja, Rio de Janeiro in Brasilien – das erwähnt Lincoln im Gespräch 1996 auch schon, ich habe den betreffenden Absatz im ersten Post zitiert: „I got a lot of mileage out of that film. I just sang a song and suddenly I was — they sent me to Europe and South America.“

Was die Musik angeht sind das keine besonders bemerkenswerten Aufnahmen. Aber sie sind auch weit entfernt davon, schlecht oder schwach zu sein Es fehlt ihnen aber das besondere Etwas. Marty Paich (nicht „Page“ oder „Paitch“, wie er im Text von Baraka heisst) hat sechs Stücke mit Streichern arrangiert, Jack Montrose und Benny Carter je drei mit einigen Holdbläsern einer Trompete (die klingt manchmal – z.B. in „This Can’t Be Love“ – sehr charakteristisch, denke eigentlich, dass gewisse Herren Kritiker die erkennen könnten, wenn sie sich nicht zu schade wären, sich in die Gefilde des Vocal Jazz hinab zu begeben?).

Lincolns Stimme ist zwar erkennbar, aber wie auf den sechs Stücken vom Juli klingt sie weniger stark als auf der frühen Single von 1954 oder im Film, als würde sie sich in der Diktion und auch bei der Gestaltung etwas zurückhalten (früher, also bevor ich mit ihrer Stimme klargekommen bin, hätte ich das übrigens gerade begrüsst, aber das war kein Werturteil sondern bloss eine Frage der persönlichen Vorlieben, dessen was gefällt, und was halt nicht). Ein kleines Highlight ist für mich Montroses Rumba (oder was das halt ist) über „Would I Love You“ (Russell-Spina):

In Paichs „Crazy He Calls Me“ (da kommt in den Passagen im Dialog mit der gedämpften Trompete dieser typische Lincoln’sche Finish, der Glanz in der Stimme, wieder zum Vorschein) kommen einzelne Xylophon-Töne zum Einsatz. Es gibt in diesen Arrangements durchaus Liebe zum Detail und einiges an Nuancen. Aber Lincoln sollte sich ganz anders entwickeln und das Album ist daher nicht zu früh oder einfach zum falschen Zeitpunkt entstanden, sondern sie ist quasi miscast hier. Für wen anderes hätten das echt gute Backings sein können. Im abschliessenden „No More“ (Camarata-Russell) wird die Nähe zu Holiday da und dort hörbar – aber grad die Abschlüsse der Songzeilen gestaltet Lincoln schon in ihrer ganz eigenen Art. Abgesehen vom harten Edit ein paar Sekunden vor Schluss (ev. hat man da einfach aus Versehen das Gesangsmikrophon zu früh ausgeknipst und es gar kein Edit?) ist das eine der stärksten Performances auf dem Album:

Billie Holiday (Decca, 1946):

Eine kleine Fussnote zum Thema Machtgefälle: Auf der Rückseite des CD-Reissues stehen nur die Namen von Carter und Paich. Auf der Rückseite des Booklets ist Jack Montrose dann auch zu finden und es steht sogar, wer welche Stücke arrangiert hat. Aber als Verkaufsargument war Montrose damals halt längst nichts mehr Wert, also streichen. Am Platz kann es nicht gelegen haben.

—

Und in diesen Kontext passt wohl auch noch die Geschichte, die Lincoln 1996 über Las Vegas erzählt:

I only worked Las Vegas a couple of times, thank God. […] Hated it. Las Vegas is a place where people go who don’t see themselves as creative. If you’re creative, you’re like in the manger. At Blues Alley, in the alley. Las Vegas is for show business. I went to Las Vegas, to Caesars Palace once and I went there with John Coletrain’s Africa. I had written a lyric to it, and I was singing „Naturally, Live for Life.“ They fired me, but Oscar Brown told me that they had fired him the same way. So, I wasn’t surprised. They fired me in the lobby and American Gilda Variety Artist let them take $6,000 of my money. It was after I had made „For Love of Ivy.“

I didn’t ask them for the job, but I could have said to them I’m not coming in. I was trying to be cooperative, you know, did my best. I wore some very beautiful garments. I was on a bill with Reagan’s daughter, Mickey Rooney’s son, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Hilton’s daughter. They had all these names on the marquee. Hilton, Reagan, Rooney, and my name Lincoln. So, I was — and they had me close the show, right? They had already opened it. It was a disaster. It had been there for about a week and the conductor told Roach, „She can’t save the show.“

So, I would come on the stage and I would say to them, „Well, it’s interesting that Caesar’s Palace is featuring the children of famous people this week. It’s a very well-kept secret, but as a matter of fact, I am the great-great-great illegitimate daughter of Abraham Lincoln,“ and they would laugh, but I didn’t have anything to follow it with.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #170: Aktuelles von Jazzmusikerinnen – 19.02.2026, 20:00; #171 – 10.03.2026, 22:00; #172 – 14.04.2026, 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba