Startseite › Foren › Über Bands, Solokünstler und Genres › Eine Frage des Stils › Blue Note – das Jazzforum › Ornette Coleman

-

AutorBeiträge

-

Ich habe dieses WE eher durch Zufall die Ornette Coleman Box „Beauty is a rare thing“ relativ günstig gekauft.

Ich habe mich mit Coleman sehr schwer getan, seine Ideen waren mir so unstrukturiert. Doch dieses mal hat mich die Musik gepackt. Ich habe nur die ersten zwei CDS gehört bin vor allem von dem Album „Jazz New Shape to come“ in dem vorallem Don Cherry und Coleman brillieren in dem gleichzeitig improvisierte Solos spielen, die perfekt zueinander passen. Charlie Haden hat zudem tolle Solos in den Breaks.

Die Musik war damals eine Revoloution Davis und Gillespie haben ihn zerissen, weil er angeblich sein Instrument nicht beherrschte. Coleman hat sich das Saxophonspiel selber begebracht.

Dieses Coleman Quartett war absolut briliant , bin froh nach vielen Jahren auch diesen Bereich ergänzt zu haben.

Mögt ihr Coleman oder ist er ein Spinner?

--

Highlights von Rolling-Stone.deWerbungalexischicke

Mögt ihr Coleman oder ist er ein Spinner?Ich mag ihn weil er ein Spinner ist!

--

Charles MingusYou didn’t play anything by Ornette Coleman. I’ll comment on him anyway. Now, I don’t care if he doesn’t like me, but anyway, one night Symphony Sid was playing a whole lot of stuff, and then he put on an Ornette Coleman record.

Now, he is really an old-fashioned alto player. He’s not as modern as Bird. He plays in C and F and G and B Flat only; he does not play in all the keys. Basically, you can hit a pedal point C all the time, and it’ll have some relationship to what he’s playing.

Now aside from the fact that I doubt he can even play a C scale in whole notes—tied whole notes, a couple of bars apiece—in tune, the fact remains that his notes and lines are so fresh. So when Symphony Sid played his record, it made everything else he was playing, even my own record that he played, sound terrible.

I’m not saying everybody’s going to have to play like Coleman. But they’re going to have to stop copying Bird. Nobody can play Bird right yet but him. Now what would Fats Navarro and J.J. have played like if they’d never heard Bird? Or even Dizzy? Would he still play like Roy Eldridge? Anyway, when they put Coleman’s record on, the only record they could have put on behind it would have been Bird.

It doesn’t matter about the key he’s playing in—he’s got a percussional sound, like a cat on a whole lot of bongos. He’s brought a thing in—it’s not new. I won’t say who started it, but whoever started it, people overlooked it. It’s like not having anything to do with what’s around you, and being right in your own world. You can’t put you finger on what he’s doing.

It’s like organized disorganization, or playing wrong right. And it gets to you emotionally, like a drummer. That’s what Coleman means to me.

Blindfold Test mit Leonard Feather, Teil 2, Down Beat, 12. Mai 1960

http://mingusmingusmingus.com/mingus/blindfold-test--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaich finde vor allem die frühen sachen („shape of jazz“, „change of the century“, „free jazz“, „chaquappa suite“ (oder so ähnlich) sehr gut… später hat er „nur“ mehr alle 10 jahre ein meisterwerk gemacht („skies of america“, „dancing in your head“, „virgin beauty“)… ein genie…

--

i don't care about the girls, i don't wanna see the world, i don't care if i'm all alone, as long as i can listen to the Ramones (the dubrovniks)Die frühen Einspielungen begeistern mich einfach und sie sind für mich sehr mitreissend.

‚Kompliziert‘ wird es sicher schon ein wenig mit dem Album „Free Jazz“, aber tatsächlich geht es mir dann nachfolgend so, dass es mir recht schwer fiel, einen Zugang zu finden zu den späteren Veröffentlichungen.Gleichwohl folgten geniale Einspielungen, sie wurden bereits genannt, aber gefühlsmäßig passten Ornette und ich nicht immer zusammen. Seine Musik beinhaltet Elemente, die recht sperrig wirken, Elemente, auf die man sich erst einlassen muß, intellektuell…

--

An die elektrischen Aufnahmen nähere ich mich immer noch an – sehr langsam, aber sie gefallen mir immer besser.

Ansonsten, die Atlantic-Box ist grandios – ich hatte einige Alben davor einzeln und finde es klasse, die Aufnahmen komplett und am Stück zu hören (es gab ja drei LPs mit „Resten“, die in der Box bei den jeweiligen Sessions einsortiert sind). Haden entwickelt hier bereits sein Bass-Spiel, das – ich komme um den Vergleich nicht herum – so prägend für jede Gruppe ist, in der er auftaucht, wie es sonst wohl nur bei Mingus, vielleicht noch bei Wilbur Ware der Fall ist (ich lese – s.u. – gerade wieder, dass Haden Ware als grosses Vorbild betrachtete). Im Gegensatz zu Mingus wirkt das bei Haden aber immer äusserst bescheiden, es geht nicht um Egos sondern bloss um Dienst an der Musik.

Ornette und Cherry kann man wohl als eine Art „Update“ von Bird und Diz betrachten, wenn man mag – ihr beinah telepathisches Zusammenspiel ist jedenfalls ähnlich.

Ich habe mir gerade die Mühe gemacht, John Litweilers brillante Analyse ausgiebig zu exzerpieren – da das so umfangreich wurde, packe ich es der Lesbarkeit zuliebe nicht in kursive Zitat-Kästchen. Zwischen den Posts gibt es jeweils weitere Auslassungen im Text, alle anderen sind durch „[…]“ gekennzeichnet. Leerzeilen zwischen den Absätzen gibt es im Buch natürlich nicht, aber das das am Bildschirm die Lesbarkeit enorm erleichtert, habe ich sie eingefügt.

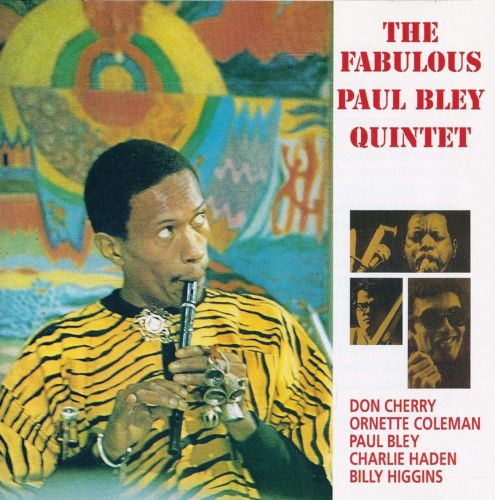

________________________In February 1958 Ornette Coleman recorded Something Else!; his quintet included Don Cherry, trumpet, and Billy Higgins, drums. In the liner notes he offers the principle that motivates his music’s freedom of expression: „I think on day music will be alot freer. Then the pattern for a tune, for instance, will be forgotten and the tune itself will be the pattern, and won’t have to be forced into conventional patterns. The creation of music is just as natural as the air we breathe. I believe music is really a free thing, and any way you can enjoy it you should.“

Here is the Freedom principle. The era of Free jazz begins with this first document. Something Else! made little impact at first, and Coleman’s only musical gig the rest of the year was when he, Cherry, and Higgins played for six weeks with pianist Paul Bley (Coleman almost never again performed with a pianist). (S. 34)

[…]

Coleman’s alto soloing [auf den Aufnahmen von 1958] is shot through with the adrenaline of Charlie Parker, the aggression of Parker in blues such as „Alpha“ and two versions of „When Will the Blues Leave?“ His broken, irregular phrasing suggests the contours of early Parker or, in the first version of „Ramblin‘,“ a heretofore missing link between Charlie Christian and Parker; the exultant, leaping phrases and the undercurrent of loneliness in his sound fill a thirteen chorus blues solo, a summary and summit of southwestern style. In every solo, Coleman plays phrases that turn around the beat, or accents fall asymmetrically, or phrases are spaced so that they begin irregularly within bars; this rhythmic acuteness leads to an ever-present sense of danger, of disguised, coiled accents striking at arteries. Coleman’s essentially diatonic phrases also become tense with ancular intervals, and his shifting tonalities add yet more tension with their apparent harmonic irresolution. In solos such as „Klactoveedsedstene“ the sound of his alto moves, from phrase to phrase at times and sometimes even within phrases. (S. 34f.)

________________________aus: John Litweiler, The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, New York, 1984, Chapter 2: Ornette Coleman: The Birth of Freedom, S. 31-58

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba

But empathy evolved from Haden’s extensive rehearsing with Coleman, and in the 1959 Atlantic sessions you can hear how well Haden understood the general directions of Coleman’s and Cherry’s harmonic motions. Haden chooses bass tones that relate ambiguously or consonantly to the soloists‘ phrases, in lines that derive from the soloitsts‘ movement (including the times when he creates harmonic counterpoint). Haden has credited Wilbur Ware’s major influence on his own style, and in amplifying the good humor of Coleman in „Music Always,“ haden proves to be another virtuoso of rhythmic spontaneity. The Coleman Quartet anticipates some of the Ayler groups‘ independence in „Change of the Century,“ in which Haden arrives at an apex of spontaneous contraditions; the soloists advance despite his insults. It’s the bass solo that begins the distortion of reason and emotion in „Focus on Sanity“; the unstable dissonances that rise in his solo are the suppressed form of the mad yelps and lashing trills in Coleman’s. (S. 37)

[…]

What’s happening is thematic improvisation. It’s not the Rollins way, in which motivic recall is central among the linear and dramatic solo elements, but more like the way of Benny Carter in Swingin‘ the 20s (1958) or such earlier solos as „Crazy Rhythm“ (1937), in which the essense of a motive informs every phrase of the improvisation. Coleman’s motivic evolution is a matter of continually reshaping the initiating cell. Even if specific intervals become approximate, the rhythmic shape remains, intact, compressed, or extended; far less commonly, the intervallic shape remains while the rhythmic shape is distorted; the cell motive is heard at the beginning, within, or at the end of phrases; it is upended, turned on its side, and viewed from different perspectives again and again; its meaning is altered and renewed. (S. 38)

[…]

The Coleman Quartet’s „Ramblin'“ is quite different from the 1958 „Ramblin'“ by the Bley Quintet. This new performance certainly recalls Kenneth Rexroths’s often-quoted remark about Coleman: that „the whole group is from the Southwest, and behind them you can hear the old bygone banjos and tack pianos, and the first hard moans of country blues.“ Though „Ramblin'“ remains a blues, the freely substitued-upon changes stretch to irregular lengths, even in the theme; bravado begins, answered by the strummed bass; reality confronts the bravado, then another bass reply; the third theme phrase is two bars by the horns in unison, after which they separate to ride their ramshackle ways on the frontier of myth. In solo, Coleman’s phrases come from Kansas City and country music, excitement and singing appear, and a growl becomes a dynamic motive. Responding to this prairie solo, Cherry is witty and personal, his jaunty lines spitting tobacco as he rides the landscape. Haden’s strummed replies in the theme are a Bo Diddley vamp which then alternats with walking choruses in his accompaniments; the vamp reminds us this frontier is vast and lonely, even if the loneliness is as stylized as a cowboy song of abandoned love. Moreover, this syncopated drone is exttracted whole from folk musc — Haden had been inspired by his brother, a bassist in country music bands — and his bass solo in „Ramblin'“ is even a strummed bluegrass song. Even the fleeting satires of Coleman and Cherry are a feature of folk humor; like a Jimmy Yancey solo, the folk sources of „Ramblin'“ are not betrayed but parodied, distorted, or otherwise set at a distance: „Ramblin'“ is folk myth. It fades on trumpet and chirping alto surrounded by the Western panorama and ends by snapping out the abrupt reality phrase, and you take for granted that „Ramblin'“ does not end in these final notes. (In jazz, as in history, the sequel to „Ramblin'“ came seventeen years later, in Charles Tyler’s Saga of the Outlaws.) (S. 39f.)

[…]

[H]ere is a bit of trivia from Dorothy Kilgallen’s New York Journal-American gossip column that captures the flavor of the period’s publicity: „Leonard Bernstein took his family to the Five Spot to hear Ornette Coleman, who seems the musician most likely to affect the history of jazz this season, although many of his fellow players … maintain that his offbeat style won’t have a lasting effect. More objective aficionados think he’s fabulous.“ (S. 40)

[…]

Coleman himself saw no reason why any music that was as natural as his should continue to be so controversial.

The crisp, precise drummer Billy Higgins left the quartet in the spring of 1960 and was replaced by Edward Blackwell, from the New Orleans bop underground. Blackwell advances the New Orleans tradition of not just accompaniment but, as pioneer Baby Dodds would have said, „playing for the benefit of the band.“ His time provided the quartet a subtle, behind the beat, and almighty swing, while his palette of sounds added new depth of color. And now an element of black humor entered their expressive capacities. The major result of their three midsummer recording sessions was This Is Our Music, and much of the rest is on To Whom Who Keeps a Record, issued only in Japan. (S. 41)

[…]

Coleman says, „… I realized that if I changed the harmonic structure or the tempo structure while someone else is doing something, they couldn’t stay there, they’d have to change with me. So I would bring that about myself a lot, knowing where I could take the melody and then show the distance between where I could go and still come directly back to that melody, instead of trying to show the different inversions of the same thing.“ Here is an orchestral work that’s improvised without tempo or meter, that moves into abstract tones and tonalities, yet that develops a detailed musical conception to its conclusion. Even though „Beauty Is a Rare Thing“ was recorded as early as 1960, the doors it opens would not begin to be explored in jazz for several years yet. (S. 43f.)

[…]

The album with LaFaro, Ornette!, has the three longest solos Coleman had recorded to date, all in the same medium-fast tempo, all organized via motivic evolution. These January 1961 solos may have modified the spontaneity of his earlier improvising in favor of formal unity, but in terms of rich variety of phrasing and lyricism nobody else in jazz at the time approached the quality of Coleman’s playing. (S. 44)

[…]

Free Jazz is a collective improvisation by the Ornette Coleman Double Quartet: Coleman, Cherry, LaFaro and Higgins on the left stereo channel, and Freddie Hubbard, trumpet, Dolphy, bass clarinet, Haden, and Blackwell on teh right. Each player „solos“ for several minutes while the others create lines inpsired by the soloist or are silent if they choose to be; also, the soloist may choose to improvise upon what he hears in the others. The objective is spontaneous ensemble structure achieved through responsive, simultaneous motivic development. Textures continually change from one to all four horns, over the rhythm. Don Cherry proves the readiest, most varied player here, and during his „solo“ section the collective ideal is most nearly realized; twice Cherry permits Coleman to assume the lead voice and concludes by playing obbligato to a Coleman-Dolphy game of phrase catch. (S. 47f.)

________________________aus: John Litweiler, The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, New York, 1984, Chapter 2: Ornette Coleman: The Birth of Freedom, S. 31-58

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba

David Izenzon brought a major advance in jazz bass playing and in the structure of the jazz ensemble. Izenzon was born in 1932 in Pittsburgh and did not even begin to study bass until he was twenty-three years old; he became Coleman’s bassist five years later. Traditionally the bass’s role in jazz had been to ground the ensemble pulse; even LaFaroe, though he chafed at the role, did not find an alternative. But Izenzon was as likely to provide the melodic line as pulse, avoiding direct rhythmic reference, contradicting his partner’s tempos, and playing arco at least as often as he played pizzicato. The genius of Izenzon’s music is that he did not become an independent voice in the trio; his fine sensitivity created ensemble tension so that in a discursive peformance such as „The Ark,“ with shifting tempos and problematic drumming, Izenzon becomes a source of unity. When Coleman plays hard alto trills, Izenzon fiddles wildly in double stops; when drums and sax separate in fast tempos, the bass separates further with a slow, plucked line. In the middle he plays a shimmering note that begins a continuous melodic line, a characteristic solo: brief, compact, a complete statement utterly free of ornamentation. After the self-dramatizing of Mingus and LaFaro, it’s a paradox that Izenzon, the most active of bass virtuosos, sounds so completely effortless. You’re not overwhelmed at his speed; his music flows so naturally and lyrically, without excess, that even his blurring of pitch does not sound extreme. Izenzon was especially devoted to bass sound. At a time when electronic amplificatoin was becoming standard for jazz bassists, he didn’t use an amplifier even though he played softly; ealso, his experience in both jazz and contemporary classical techniques gave him a broad expressive range. (S. 49f.)

[…]

In contrast with the increasing stylization of his alto soloing, there’s his violin and trumpet work of the sixties. He had no teachers or guides to playing these instruments; he purposely avoided learning standard techniques, for his objective was to play „without memory“ and to create as spontaneously as possible. He had jammed with Albert Ayler in 1963; Ayler’s concept of sound, especially his deliberate imprecision of pitch, certainly coincides with Coleman’s point view: „I’m very sympathetic to non-tempered instruments. They seem to be able to arouse an emotion that isn’t Western music. I mean, I think that European music is very beautiful, but the people that’s playing it don’t always get their chance to express it that way because they have spent most of their energy perfecting the unisons of playing together by saying, ‚You’re a little flat,‘ or ‚… a little sharp.‘ … A tempered note is like eating with a fork, where that if you don’t have a fork the food isn’t going to taste any different.“

Despite a unique sound, Coleman’s trumpet phrasing at first tends to sound like blurred, flighty abstracts of his sax phrasing; a lifetime’s habit of breathing is retained on the new wind instrument. But the violin is a stringed instrument, so Coleman could create lines without the necessity to regulate phrasing and breath; his nontempered violin improvisations sound indeed like music without the distortion of will. The admiring critic Max Harrison considered them „an indeterminacy as drastic as John Cage’s.“ In „Falling Stars“ and „Snowflakes and Sunshine“ Coleman and Izenzon together create thick forests of string textures, sustained by kinetic energy. The most extensive and varied example of Coleman’s trumpet playing is in one of his rare appearances as a sideman on altoist Jackie McLean’s New and Old Gospel. The trumpet phrases glitter through the many collective improvisations; Coleman sustains a delicate tension of sound and space in „Vernzone“; the trumpet lines become sober against the bronze, beautiful alto tones in „The Inevitable End.“ McLean’s raw, powerful sound and accenting are gothic next to the airborne, mostly muted Coleman; this altoist, too, vividly and naturally plays sharp or flat „in tune.“

Charles Moffett, Coleman’s regular drummer, was a master of many styles and among the most sophisticated of percussion technicians. There could be no greater contrast than Coleman’s ten-year-old son, Denardo, who is the drummerin The Empty Foxhole (1966), without style or more than rudimentary technique, but with a welcome spontaneity, a further setp in the direction of indeterminacy. The Crisis concert (1969) is a major recording, a reunion with Don Cherry that introduces new compositions (including „Broken Shadows“) into the Ornette Coleman repertoire. Is Denardo Coleman’s presence, his spontaneity, in some degree an inspiration for the insene immediacy of Crisis? One glittering statement is unaccompanied: Ornette’s powerful melodic structure that begins his „Song for Che“ alto solo. (S. 50-52)

[…]

After he had returned to America in mid-1966, he again slowed down his performance schedule. He was disgusted with the way the music business treated musicians, and he said, „I don’t feel healthy about the performing world anymore at all. I think it’s an egotistical world; it’s about clothes and money, not about music. I’d like to get out of it, but I don’t have the financial situtation to do so. I have come to enjoy writing music because you don’t have that performing image. … I don’t want to be a puppet and be told what to do and what not to do. …“ (S. 52f.)

________________________

aus: John Litweiler, The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, New York, 1984, Chapter 2: Ornette Coleman: The Birth of Freedom, S. 31-58

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba

His performing trio became a quartet with the addition of Haden in 1967; after that, Haden, Redman, and Blackwell were his most frequent sidemen. And as Coleman cut down his touring schedule, he presented conceerts in his home, Artists House, on Price Street in Manhattan, sometimes performing there himself, other times introducing other musicians to his audiences.

When his quartet played at a Lisbon, Portugal, jazz festival in November 1971, Charlie Haden dedicated his „Song for Che“ to „the Black people’s liberation movements of Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea“; the audience cheered at length, and Redman and Blackwell gave the raised-fist salute. The police canceled the day’s second concert but then changed their minds and let it go on. Nonetheless, as the quartet was boarding their plane the next day, Haden was arrested and was released only upon the intercession of the American cultural attaché. (S. 53)

[…]

He completed his twenty-one movement Skies of America in 1971, and the next year conductor David Measham recorded it with the London Symphony: Coleman improvised on alto throughout much of the work’s second half. These Skies are often clouded; movements in long, held tones turn into fast, jagged sections; „Foreigner in a Free Land“ features some of his very harshest alto playing, and „The Men Who Live in the White House“ includes his unaccompanied solo. His melodies are gay, or they are troubled and disturbeing, and what lingers in the music is the floating feeling of light, dark, and the turning earth. […] he said Skies is „the way I play.“ (S. 54)

[…]

In the Skies of America liner notes, he first mentions his „Harmolodic Theory, which uses melody, harmony, and the instrumentatione of the movement of forms.“ Later he said harmolodics „has to do with using the melody, the harmony and the rhythm all equal,“ and Don Cherry described harmolodics as „a profound system based on developing your ears along with your technical proficiency on your instrument.“ Just because harmolodics is a system, it can’t be defined in a simple sentence or two, but the word stands for what Coleman taught his first groups back in the 1950s: a wide knowledge and experience of ways to join Free lines into an ensemble music. Needless to say, harmolodic improvising demands great skill of listening and response; Coleman says it took years to teach his system to his first band, and again it took years to train his Prime Time band.

________________________

aus: John Litweiler, The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, New York, 1984, Chapter 2: Ornette Coleman: The Birth of Freedom, S. 31-58

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tba

This is the source of Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time: „Aboud 1974-75, I realized that the guitar had very wide overtones — one guitar might sound like ten violins. Like, say, in a symphony orchestra two trumpets are the equivalent of twenty-four violins; that kind of thing. When I found that out, I decided, then I’m going to see if I can orchestrate this music that I’m playing and see if it can have a larger sound — and it surely did.“ The result is not exactly jazz but a kind of Free jazz-rock idiom. It’s as far removed from Coleman’s Free jazz as from his classical music, and the term „harmolodics“ has come to be associated entirely (and therefore inaccurately) with this idiom.

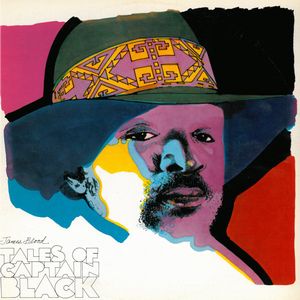

Coleman’s first two Free jazz-rock albums were by a quintet, in December 1975; the third album, Of Human Feelings (1979), is by six players; and in the eighties Prime Time is a septet of Coleman, three „lead“ players, and three „rhythm“ players — the lead and rhythm unites are each guitar, bass, and drums. The lead players don’t solo but create streams of interplay with each other and with Coleman’s alto lines, which ride atop the ensemble. Prime Time moves in layers of tempos: Some players double Coleman’s time, some halve it, and the lead guitarist is the only one who now and then breaks away from dotted eighth-sixteenth note patterns. The foundation of the rhythm is the disco thud of the bass drum on each beat; some pieces, like „Macho Woman,“ use a bass drum Bo Diddley beat (compare this to the flowing Bo Diddley rhythm in „Ramblin'“). Coleman’s top lines are in always changing tonalities, and therefore, the others‘ separate tonalities keep changing, too; everyone is constantly modulating, as in Free jazz. Of Human Feelings is far superior to the 1975 LPs, but James „Blood“ Ulmer’s (James Blood’s) Tales of Captain Black, on which Coleman plays alot, is yet a better fusion of Free ideas with rock-pop methods. So far records haven’t captured the spirit of Coleman and Prime Time in concert: an urban rhythmic tribe, with a fluid alto sax dipping and curving throug the merry clatter of loud rock, jerk, and bump.

Coleman’s improvising with Prime Time is nonstop; his inventive stamina is amazing. In general, his playing has become simpler, with less detail, repeated phrases, accented beats, and proliferating sequences. His songs for Prime Time lack the earlier definition of emotion in his composing; his Free jazz-rock is obviously more rhythmically restricted in any case. (S. 55-57)

[…]

The wide-open spaces of Ornette Coleman’s pre-Prime Time repertoire have been left to Old and New Dreams, the quartet of Cherry, Redman, Haden, and Blackwell. No great artists communicates the insights and values he or she offered twenty-five years ago, and Coleman is no longer the radical young bebopper from Texas — „The pain is still there, but it’s not as detrimental as I used to think it would be.“ He’s long since become cosmopolitan, a thorough urbanite with a big-city dweller’s nerves and emtions. Now his music appeals directly to no longer the heard and mind but the neves, reordering the congestion of life’s images and emotions with infectious patterns and simple songs. What persists is the fastination of his music itself and of his urge for discovery, as he continues to transform the jazz tradition. (S. 57f.)

________________________

aus: John Litweiler, The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, New York, 1984, Chapter 2: Ornette Coleman: The Birth of Freedom, S. 31-58

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaGypsy ich kann das doch nicht alles lesen.

Miles Davis und Manyard Ferguson haben ihn in der Luft zerissen, sie meinten, dass er nicht sein Instrument beherrschte. Das stimmt auch ein bisschen, ein Ben Webster spielt die Noten viel schöner als Coleman.

--

Natürlich kannst Du – in den wenigen Sätzen wird sehr viel auf den Punkt gebracht, auf eine Weise, wie ich das selbst nicht könnte. Und die Passagen über Prime Time machen mir auch gleich wieder Lust, die Sachen mal wieder hervorzuholen. Ornette ist ein verdammt cooler Hund!

Ich möchte übrigens gerne das Photo von Lenny und Familie mit Ornette sehen, falls das jemand hat.

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaOrnette Coleman Seeks to Block Bootleg

By MIKE HEUER(CN) – Two musicians bootlegged live private recordings of jazz great Ornette Coleman and continue to offer the illicit materials for sale, the bandleader and his son say in a federal lawsuit.

In a federal complaint filed in White Plains, N.Y., on May 19, Denardo Coleman, the eldest son and guardian of Ornette Coleman, accused drummer Amir Ziv, trumpeter Jordan McLean and System Dialing Records of using live recordings of Ornette Coleman in violation of the federal Anti-Bootlegging Act.

Denardo says Ziv and McLean are „fixing, reproducing, communicating, publicly distributing, selling, and trafficking in unauthorized recording of live musical performances“ by Ornette Coleman.

The musical work is entitled „New Vocabulary“ and is listed for sale in its entirety or as individual songs in several downloadable formats at the System Dialing Records‘ website.

The site claims the work is „a new collaboration“ by Ornette Coleman, McLean, and Ziv. Adam Holzman plays on piano on three of its 11 tracks. The site also says the work is produced by McLean and Ziv.Fortsetzung hier:

http://www.courthousenews.com/2015/05/21/ornette-coleman-seeks-to-block-bootleg.htm--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaDie seltsame Geschichte geht weiter:

http://jazztimes.com/articles/161947-ornette-coleman-sues-over-release-of-new-vocabulary-album

http://www.star-telegram.com/entertainment/arts-culture/article21712986.htmlUnd die Gegendarstellung:

In an email to NPR late Wednesday afternoon, Ziv wrote, „New Vocabulary is a collaborative, joint work by professional musicians Jordan McLean, Amir Ziv, and Ornette Coleman, made with the willing involvement of each artist. The album is the end result of multiple deliberate and dedicated recording sessions done with the willing participation and consent of Mr. Coleman and the other performers. Any suggestion to the contrary is unfounded and we deny any allegations of wrongdoing. For any further comment, we refer you to our attorney Justin S. Stern at Frigon Maher & Stern LLP.“

http://www.npr.org/2015/05/27/410065414/ornette-coleman-sues-over-new-vocabulary

--

"Don't play what the public want. You play what you want and let the public pick up on what you doin' -- even if it take them fifteen, twenty years." (Thelonious Monk) | Meine Sendungen auf Radio StoneFM: gypsy goes jazz, #168: Wadada & Friends - Neuheiten 2025 (Teil 2) - 9.12., 22:00 | Slow Drive to South Africa, #8: tba | No Problem Saloon, #30: tbaeiner der freiesten musiker überhaupt. mir würden spontan noch einige tolle kollaborationsprojekte für ihn einfallen.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/12/arts/music/ornette-coleman-jazz-saxophonist-dies-at-85-obituary.html?_r=0--

-

Schlagwörter: Ornette Coleman

Du musst angemeldet sein, um auf dieses Thema antworten zu können.